Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How company culture drives growth

One manufacturing company’s behavioral approach to culture development

- By Tim Heston

- October 12, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

PCI moved to its current location in 2005, purchased and expanded into a nearby building in 2011, and grew into yet another nearby building in 2017.

Company mission, vision, or value statements ring hollow sometimes, often because of how vague they are. A company can strive to be “the premier metal fabricator in the market,” but what exactly does that mean? Reputation is important, but it’s also tough to define and measure. Sometimes a mission statement could describe something objective—like world-class on-time performance—but it’s still an end; the means to get there remains undefined. Because these statements lack specifics, they’re difficult to act on.

Precision Cut Industries, a contract manufacturer in Hanover, Pa., takes a different approach. The 130-employee company operates under what it calls the PCI Way, entailing a list of behaviors. At first glance, it sounds like your typical, broad company-values document, particularly when you read the first statement:

Deliver world-class service. “It’s all about the customer experience. Do the little things as well as the big things that surprise and create the ‘wow.’ Make every interaction stand out for its helpfulness. Create loyalty by always doing what’s best for your customer, both internal and external. Do what whatever it takes and go above and beyond what’s expected. Understand their needs and put them ahead of our own.”

Employees at PCI spent time crafting that statement, but they didn’t stop there. They went on to develop 29 more behaviors —or “fundamentals,” as the company calls them—each relating to the next. Add them all up and you get actionable detail.

Some History

PCI launched in 1998 as a laser cutting specialist. When Brian Greenplate purchased the business from the founders in 2004, it had 27 employees and it was operating like a typical startup, though on a significant growth path. Annual revenue was about $3 million.

“The founder did a fantastic job launching and running the company,” Greenplate said. “As everyone knows, this is a capital-intensive business, so just getting it off the ground can be really hard.”

At the time, Greenplate saw a job shop that was gaining a good reputation, but like many startups, it lacked structure. It had no formal sales and estimating process. Quality was topnotch, but the process itself lacked documentation.

It was all very different from Greenplate’s previous employer, a $5 billion German manufacturer of systems used in hydropower equipment, where he was executive vice president of the North American division. But after 17 years, he knew it was time for a change, and made the leap.

So what changes did he make at PCI after that leap? “We didn’t do anything magical,” he said. “I tried to bring the structure of a large corporation while still maintaining the flexibility of a small company. We instituted and documented best practices and instituted estimating spreadsheets and other processes. This included achieving ISO:9001 certification. More recently we’ve ramped up our sales process. I’ve been in sales my whole life, but it’s like the lean journey. You’re never done. How can we continue to get better?”

Part of this entailed expanding the process portfolio, acquiring equipment and companies. It purchased press brakes, expanded its welding capabilities, and in 2015 purchased a fabricator in Beltsville, Md., expanding PCI’s customer base and capabilities. While PCI in Hanover has specialized in laser cutting for most of its history, the Maryland plant has expertise in punching.

President and CEO Brian Greenplate purchased PCI in 2004. Before that, he was executive vice president at a large hydropower equipment manufacturer.

Building Culture

Expertise is important, because as Mike Noll, vice president of sales and marketing, explained, without expertise, customer service becomes difficult. The company has 12 lasers, 10 press brakes, and all the trappings of a modern fab shop that maintains and updates modern machinery. But these aren’t proprietary machines, of course, and if a competing shop has available funds, there’s nothing stopping it from making similar investments. But people, and the culture they create, can’t be copied. “That’s why over the past couple of years, we’ve really been focused on our company culture,” Noll said.

“We had focused on our culture for a long time,” Greenplate said. “We had about seven stated values. And yes, it was nice to put those values on the wall, but they didn’t drive action. What do we do every day when we come to work to support those values?

“Several years ago, I felt our culture was stuck. Yes, we had a good culture and a good management team, and we all understood it, but how could we drive it down through the rest of the organization?”

Greenplate belongs to an executive coaching organization called Vistage International, and during one local chapter meeting, he listened to a speaker who described a behavioral-based approach to culture. He eventually invited the speaker to work with the company as a consultant.

As Greenplate recalled, “I then asked our management team, ‘How would we take our current values and make them actionable? What are the behaviors that support them?’ This initiated a process that led to where we are today.”

A Problem at the Press Brake

The 30 fundamentals—communicated throughout the company and posted on its website (www.pcilasercut.com)—drive weekly huddles in various departments. Each huddle is dedicated to the weekly fundamental. Once the team makes it through No. 30, they start again at No. 1. The point is to instill specific behaviors that aren’t the easiest to adopt. After all, if they were easy, more companies would have great cultures.

So how exactly do these fundamentals drive actions and behaviors? To illustrate, Noll described a recent shop floor problem regarding time estimates on a forming job. The job packet dedicated enough time to bend one part on the press brake; thing was, the job specified a dozen pieces. The following events are hypothetical, but they help illustrate PCI’s fundamentals in action.

Imagine a longtime press brake supervisor marching into the estimating department. On the surface he’s there to ask questions, but deep down he’s there to teach people he feels should know more about forming than they currently do. His ego front and center, he assumes others are ignorant.

At PCI, fundamental No. 24 applies, Check your ego at the door. So does No. 15, Be easy to work with, which has the phrase “be ridiculously helpful.” The brake operator at PCI does not storm to the front office in anger, nor does he circle the mistake and return the job packet to his supervisor in it’s-not-my-job-to-fix-it fashion. He also uses No. 12, Assume positive intent. He assumes people act in good faith—and, in fact, he doesn’t even assume a mistake was made until he has more information.

At the same time, he also follows fundamental No. 10, Speak candidly. He won’t sugarcoat the situation; if managers really want the brake department to produce so many parts in so little time, well, the resources to do so simply do not exist.

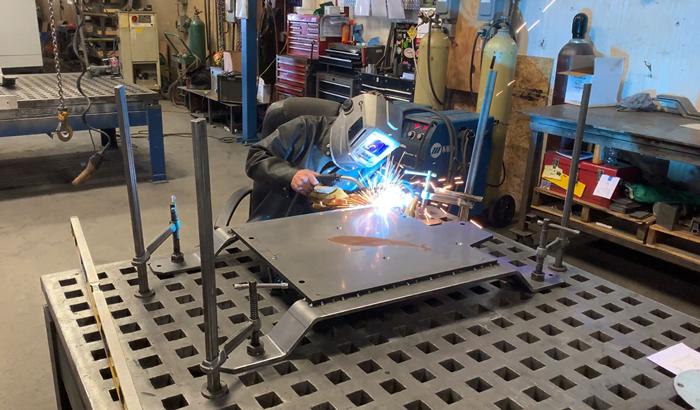

A welder completes a job on a flexible fixturing table. Every department, from welding and forming to cutting and the front office, has weekly huddles, or standup meetings, dedicated to one of the company’s 30 fundamentals.

But again, he doesn’t know what’s really wanted yet, so he doesn’t jump to conclusions. He instead speaks to the estimators and, following fundamental No. 9, listens generously. As No. 9 states, “Suspend your judgment and be curious to know more rather than jumping to conclusions.”

As Noll described it, “There are at least two parties to every conversation. One has to communicate a position effectively, and the other party has to be willing to listen to what the other person is saying.” He put emphasis on “willing.” Without the will, preconceptions, ego, and insecurity get in the way.

The brake supervisor also follows a related fundamental, No. 9, Practice blameless problem solving. He isn’t pointing fingers; he just needs to know more. In some respects he would also be following No. 7, Share the why—that is, the big picture. Yes, the problem has to do with a press brake operation, but the customer demanding those parts might be of a particular size, and the potential for future work might be huge. Knowing this puts this narrow problem in perspective.

After speaking with estimators, the supervisor quickly finds out the misunderstanding. Those parts were tabbed together on the laser, and they shouldn’t have been broken apart until after forming. Tabbed together, the 12 small parts could be formed all at once. Intention communicated, problem solved.

Sure, the estimator and others on his team fell short on No. 6, Over-communicate. “The more we’re informed, the better we can collaborate, and the better we can serve our customers. Information is one of our greatest assets. Find it, share it, and use it.”

They also fell short on No. 5, Pay attention to the details. But as Noll explained, no company has a perfect culture, just like any operation isn’t perfectly lean. Like the tools of lean manufacturing, the fundamentals give people the “cultural tools” to make things better.

In reality, solving the problem—a simple miscommunication about how parts should be formed on the press brake—took a matter of minutes. The cultural tools prevented the issue from devolving into a who-said-what quagmire.

“We’re not perfect,” Greenplate added. “This business isn’t easy. People slip up, but we always ask, ‘What happened, and how did we recover quickly?’”

A Virtuous Cycle

The first fundamental, about delivering world-class service, isn’t an unusual value statement for a company. But the last on the list, No. 30, isn’t quite so common: Keep things fun. “While our passion for excellence is real, remember that the world has bigger problems than the daily challenges that make up our work. Stuff happens. Keep perspective. Don’t take things personally or take yourself too seriously. Laugh every day.”

In one sense, the fun makes everything else possible and creates a virtuous cycle. People with healthy attitudes listen generously and overcome challenges quickly, creating that world-class customer service. This in turn spurs growth, which increases the fun—and the cycle continues.

A workplace full of egotists who keep information to themselves, fail to listen, rarely laugh, and take themselves far too seriously probably has a hard time keeping talent, causing the cultural problems to snowball. If PCI had these problems, it probably wouldn’t be the $35 million contract manufacturer it is today.

A Sampling of PCI’s Fundamentals

- Deliver world-class service

- Embrace change

- Pay attention to the details

- Listen generously

- Check your ego at the door

- Over-communicate

- Share the why

- Look ahead and anticipate

- Get clear expectations

- Be easy to work with

- Be relentless about improvement

- Make quality personal

- Get the facts

- Keep things fun

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI