President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How metrics drive a job shop’s continuous improvement

Knowing what to measure is half the battle for custom metal fabricators

- By Vincent Bozzone

- February 22, 2021

- Article

- Shop Management

The trick to boosting profits in a custom metal fabrication job shop is to first recognize what makes its business model unique. Next, measure what matters. Getty Images

Imagine a custom metal fabrication job shop owner sells the business to an investment group, which in turn hires an experienced manager from a much larger manufacturer. He has years of training in Six Sigma, the Toyota Production System, and other continuous improvement techniques. Investors hired this seasoned professional for one reason: to improve the bottom line. And over the ensuing months, that seasoned pro ends up making little if any improvement to the job shop’s financials. Why is this so?

“Transfer managers” often underestimate the difficulties of managing a job shop, which is typically smaller than the mass production environments these managers came from. People tend to equate “small” with “easy to manage,” especially when it comes to making improvements that will yield financial results. And because these managers don’t understand how a job shop works and assume all manufacturing is the same, they attempt to use mass production concepts and tools, which often makes things worse.

What Makes Job Shops So Difficult to Manage?

Feast-or-Famine Demand. Job shops must deal with the roller-coaster nature of demand. They are order-driven service businesses that produce to exact customer specifications. Unlike mass production operations where orders are disconnected from production, job shops have no work if there are no orders in the backlog. They can’t build ahead because they don’t know what they will be making.

Variation in Demand. Although job shops tend to specialize in particular types of products, variations in these specialties can be extensive. There may be significant engineering or design work required, and different orders need different production routings. This requires a fair amount of thought and often experimentation that is not necessary in a mass production operation with repetitive operations.

Level Loading. Roller-coaster demand prevents level loading, a traditional manufacturing technique for gaining efficiencies via consistency. Level loading implies a known amount of work with standard times, so it’s easier to establish the proper labor and run time required to accomplish a known amount of work. Shops will have a hard time level loading when their input fluctuates. Moreover, customers and competitive conditions dictate ship dates. Although there are exceptions, job shops generally can’t build ahead.

Capacity Management. Roller-coaster demand also makes capacity management more difficult. In times of high demand, job shops must bring additional capacity online; otherwise their lead time will stretch out, their customer service will suffer, and they will become increasingly less competitive with other shops that can deliver faster. On the other hand, in periods of low demand, job shops have an excess of (nonproductive) resources they continue to pay for.

Pricing. Work must be estimated and priced to win bids and make money. Bid too high and you don’t win the work; bid too low and you lose money. Estimating is not an exact science, and the variation in demand makes accurate estimating difficult. Compare this to a mass production, repetitive operation where time and materials requirements are calculated to the second decimal point.

There is also a great temptation to reduce prices to win work when times are slow. The problem is that companies risk filling their shop with unprofitable work, only to have no capacity left for higher-margin work when demand picks up.

Production. Variations increase the probability of mistakes and added costs. Not every order is estimated and routed correctly, and even minor errors can add to rework and scrap costs. Mass production, on the other hand, has the advantage of having the bugs worked out of production during initial runs.

Scheduling. Job shop scheduling can be extraordinarily challenging. Customers require changes; inaccurate estimates keep jobs in work centers longer (or shorter) than anticipated; outsourced work often does not come back on time; excessive rework can increase costs and overload the shop in a hurry. The difficulties go on and on.

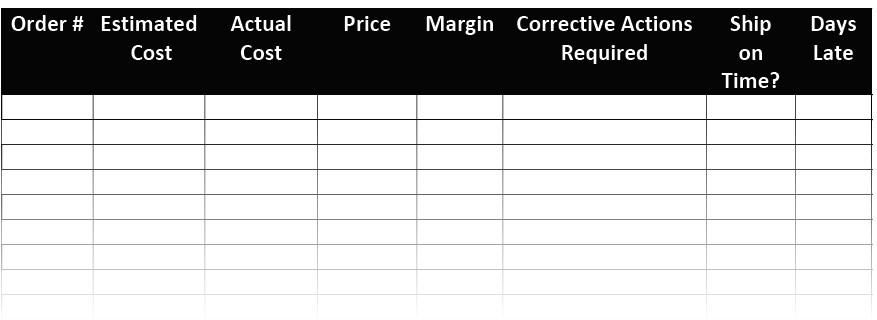

This is a useful tool for profit control in job shops. It closes the loop between estimating and shipping, and easily identifies losing and late orders. One line is completed for every shipped order, and the report is reviewed in the weekly management meeting.

Staffing. Job shops often can’t lay people off when demand is down. They’ll likely need them in the next couple of weeks, and skilled tradespeople are not easy to replace. Therefore, job shops do all they can to maintain their workforce, hoping that the downturn will be short-lived.

Cash Flow. When an order is booked, a shop is constantly spending to produce that order. Wages must be paid, materials or components must be purchased, and overhead costs must be covered. Money is constantly going out. Cash in, on the other hand, is often delayed because customers do not pay promptly. This can be particularly outrageous when a large company uses its suppliers as interest-free banks to support their own cash flow.

Customer Involvement. Customers are typically involved throughout the production process. When job shops build a custom product, the customer often inspects the work and must sign off at certain points in the process. Engineering changes can disrupt the process, and sometimes work is put on hold because the customer’s customer is having difficulties with timing or money. The point is, the customer plays an integral role in the production process, and this can create countless difficulties that slow progress and increase costs.

Changes in product specifications and production schedules create a need for job shops to have a more highly developed communications system, formal and informal. Product and schedule changes affect many people inside and outside the organization, and it’s a challenge to keep everyone informed.

Compare this with the relationship between customers and a mass production business. Customers, in the form of market demand, are indirectly related to what happens on the factory floor. Products are built to inventory, and inventory levels are adjusted based on aggregate demand, not individual customer requirements.

Planning for Growth. Job shops may have a run-up of business that looks like it will continue, but then again it may fall off. Should the shop expand or not? Should the company buy more equipment or not? Should it hire more people or not? These are difficult, sometimes risky decisions that hinge on uncertain market demand that may be impossible to predict with any degree of certainty, especially if shops depend on a small number of customers.

Equipment Utilization. Equipment utilization is a typical measure of performance in a mass production environment where much of the work is machine-paced and lines are engineered to produce similar products at high speed.

A job shop, however, might have a machine that has a very low level of utilization, yet must be available when needed. Equipment selection is not necessarily a function of how much a shop will use it; rather, a specific piece of equipment may be required to shorten lead time or reduce outsourced work and associated costs. Put another way, you might have a hammer in your toolbox, but that doesn’t mean you have to use it all the time.

Improvement Metrics for Job Shops

Once managers truly understand what makes a job shop unique, they next need to know what to measure. And again, because a job shop is fundamentally different from mass production, what managers choose to measure can make all the difference. The following examples are typical metrics that can give job shop managers a true baseline for improvement.

Sales Dollars per Payroll Hour. For hourly employees, this metric is calculated by dividing shipments (sales) by payroll hours (straight time plus overtime hours if any). This metric captures increases in sales, throughput, and productivity.

Once managers truly understand what makes a job shop unique, they next need to know what to measure. Getty Images

Let’s say a small shop with $1,200,000 a year in annual sales ships an average of $24,000 per week. Its 12 hourly employees work about 420 hours per week, so each hour worked represents $57.14 per hour in sales. By shortening lead time and increasing throughput, the company increases sales dollars per hour by 10%, to $62.86 per hour.

What is this $5.72 per hour difference worth? At 420 hours, this level of improvement translates to about $2,400 more shipped per week or $125,000 per year. However, the margin on these additional dollars shipped is extraordinarily high because only the materials costs increase. Overhead costs are already covered, and the increase in productivity covers labor costs. If the cost of materials averages, say, 28% of revenues, then 72% of these sales dollars (about $90,000) flow directly to profit.

This metric can be further refined by subtracting the cost of materials and any outside work that may be required to produce an order—heat treating, powder coating, or other outsourced operations—from dollars shipped. This may be necessary when not all the work is done in-house or when prefinished raw materials are purchased. Taking this step will tie work to time more closely, as well as eliminate false increases in performance that result from outsourcing work or buying prefinished materials. However, if all the work is routinely done in- house, and there are no changes in the pattern or type of raw materials purchased, this additional administrative work may not be necessary.

Also know that some companies measure revenue per employee. In job shops, however, revenue per employee might be a bit too coarse for measuring improvement. It’s like measuring in miles when you should be measuring in feet and yards.

Sales Dollars per Salaried Payroll Dollar. This helps measure the performance of the management and administration of the organization. Let’s say a small shop has three salaried employees and ships, on average, $24,000 in sales a week. A total salary for these employees (including the owner) is $3,000 per week. This translates into sales of $8.00 per payroll dollar ($24,000/$3,000). This can be used as a baseline against which to measure and compare organizational performance improvement and establishes a measure of accountability in this traditionally ambiguous area.

It also helps determine the increased value that results (or does not result) from adding new positions or increasing salaries. For example, let’s say the owner decides to add a new position, a general foreman, at a cost of $1,000 per week. That would decrease sales per payroll dollar from $8.00 to $6.00. The new general foreman would then be expected to provide the leadership and take the necessary actions to bring this figure back to its former level of $8.00 and higher.

Rework. This is the most expensive form of waste in a job shop; it needs to be monitored closely and managed. Look at it this way: First you pay to make it wrong; then you pay to undo what was done wrong; then you pay to redo what was done wrong; and all the time you are doing and undoing, you have lost valuable capacity that could have been used to produce salable products.

All the disruption from rework causes you to lose momentum. People on the floor become distracted. The rework disruption takes them off task, thus reducing output and adding another level of (invisible) cost. Add the cost of scrapped materials, and you can see just how expensive rework can be.

A Foundation for Job Shop Improvement

Other metrics include win-to-bid ratios, the percentage of dollars won (dollars won/dollars quoted), no-quote percentage, the percentage of orders shipped on time, as well as estimated versus actual costs. (For more information, see “3 rules for job shops to follow to avoid unprofitable work,” which you can find by typing the article title in the search box at thefabricator.com.) Shops can also measure lead times in terms of order velocity, or the speed at which an order moves through the business; that is, the days between the order entry date and the ship date. This is not a fixed number but varies with backlog and product mix.

With a baseline established, a job shop can move forward with ideas and strategies for improvement. These can include exactly how performance is reported (for more on this, see “How to track success in the job shop: Turn to the weekly performance report.”). The strategy also might incorporate some out-of-the-box thinking that can include questioning the very organizational structure of the business (see "A new look at the job shop organization chart.").

Regardless, half the battle about metrics in the job shop is knowing what matters and what is inconsequential. In fact, some traditional metrics in mass production can, when adapted to the job shop, hide deeper problems. The right metrics push those deeper problems out into the open and lead any manager—even a “transfer manager” from a very different type of operation—toward a strategy that will actually improve the bottom line.

Vincent Bozzone is president of Delta Dynamics Inc., jobshop360.com, deltadynamicsinc.com.

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI