Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Human connections at FABTECH drive metal fabrication forward

How being together again at FABTECH sparks innovation in manufacturing industry

- By Tim Heston

- August 16, 2021

- Article

- Shop Management

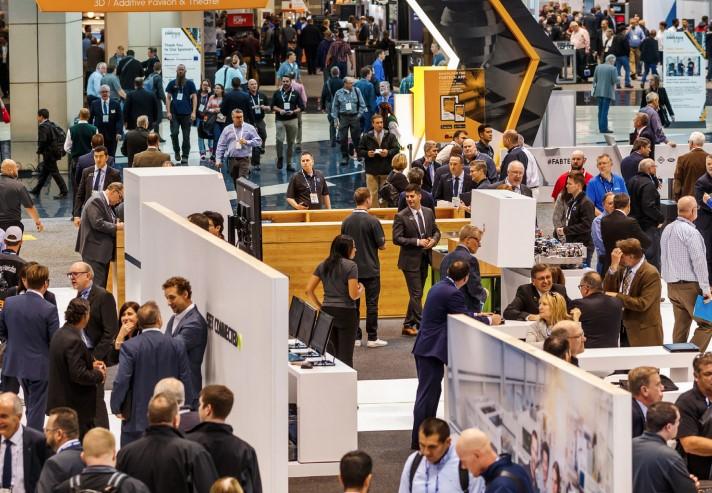

Attendees and exhibitors during the 2019 FABTECH tradeshow at McCormick Place in Chicago. Image provided

David and Jonah Stillman, a father and son team who run a consulting business called GenGuru, made some prescient remarks during their talk at FABTECH 2018 in Atlanta. David and Jonah were to meet at a client’s office. As David told the story, “We walked to the conference room and I didn’t see my son. I asked, ‘Where’s Jonah?’ They told me, ‘Oh, he’s joining via Skype.’” (This was before Zoom’s ubiquity.)

David then asked the audience how they felt about that scenario. Did Jonah (a member of Gen Z) make the meeting or was he just phoning it in? Some agreed that, yes, he did indeed make it to the meeting; he just made efficient use of technology to do so. The majority, though, disagreed strongly. A videoconference just isn’t the same as a face-to-face meeting.

I spoke with many fabricators during the pandemic, and opinions regarding in-person or virtual meetings evolved. In spring and summer 2020, many fab shop leaders embraced the technology, some even questioning their pre-pandemic travel practices. Did certain people within the company really need to visit a plant in person, or would a videoconference suffice? After all, videoconferencing seemed to be working fine during the pandemic. Would it work after?

Some fab shops wondered how they could build their virtual portfolio of sales and marketing tools. Could a fabricator bring an OEM on a virtual tour? Could a generic video be customized for certain markets? Could these videos and other virtual sales tools, an innovation spurred by necessity, evolve to complement future sales efforts after the pandemic?

Then came the vaccines and the gradual end of lockdowns. In June FABTECH’s partner associations announced the show’s return to Chicago’s McCormick Place in September. The news came at a press event with palpable excitement and relief.

“Good morning, and welcome to McCormick Place,” said Larita Clark, CEO of the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority (MPEA), the municipal corporation that owns the iconic Chicago convention center. “I’ve been waiting to say that for 15 months.” Immediate applause and cheers ensued.

The return of FABTECH Sept. 13-16 signals the return of the industry at its best: People coming together to find a better way to make things. And “coming together” is the critical part. We spend so much of our lives in a virtual realm, but as we now know all too well, such a life isn’t fulfilling. We might be virtually there, but we’re not there. The fact everyone needs to be there, all in one place to make tangible things of value, is the reason many get into the manufacturing business in the first place.

Metal fabrication doesn’t happen on a PowerPoint. It happens—with the strike of an arc, a stroke of a punch, or the piercing of a laser beam—between a tool and sheet metal (or plate or structural beam or tube or pipe). And people need to come together, on the shop or on the FABTECH expo floor, to make it all happen.

A Horizontal Business

Fabricators are a curious bunch. They appreciate visiting other operations, especially those that serve completely different niches or focus on different manufacturing processes. A metal fabricator can learn a lot from a textile plant or even a food processor. Similarly, fabricators can learn a lot from FABTECH thanks in part to the diversity of its audience and the technology on display.

I recall having lunch at the Las Vegas Convention Center in 2012 with the owner of a four-person operation just outside Bethel, Alaska, specializing in fabricating and welding residential water systems. Next to him was a manufacturing engineer at GE Appliances & Lighting in Louisville, Ky. The industry’s largest annual event drew both of these individuals from opposite ends of the continent. They sat at a table near the expo floor with the continual clatter of punch presses in the background and chatted about welding and shared ideas. More than likely, these two would never have met each other at any other professional setting outside FABTECH. They certainly couldn’t have run into each other on a Zoom call.

These two work in vastly different sectors and yet share a common thread of metal fabrication and welding. The fact that metal fabrication is a horizontal business spanning countless vertical markets—from automotive and appliance manufacturing to residential-well fabrication, along with various types of custom metal fabrication suppliers and service centers—makes a tradeshow like FABTECH all the more valuable. In fact, the attendees likely feel more at home at FABTECH than they would at an event dedicated to the industry verticals they serve. They go to those industry-vertical events to network and sell their services. They come to FABTECH for those reasons, too, but they also come to learn. The people they’re likely to meet work in different worlds, but they live in the same boat and share similar struggles.

Chief among these involve hiring and training as manufacturing evolves both technologically and culturally. Baby boomers remember spending years learning a job. They lived through globalization, the recession of the early 2000s, and the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009. Through it all, their knowledge kept them employed. It’s no surprise that some are reluctant to share it, and it’s an issue that past FABTECHs haven’t shied away from.

“A culture that fights knowledge transfer is probably going to kill that company off eventually.”

So said Dean Steadman, CNC education program manager for FANUC America Corp., Rochester Hills, Mich., during a skilled labor panel discussion at FABTECH 2019. “I think we really need to utilize all the generations of the workforce. Other kinds of people might have different ways of thinking. Others with 30 or 40 years of experience are about to retire. Let the experienced take the new people under their wing. Let them work together, perhaps implement some version of their new ideas and see where it takes you. We need to find the synergy and new way of doing things.”

This might be top of mind for many FABTECH attendees this year. With the stock market at record highs, experienced workers who had delayed retirement during the pandemic might be heading for the door. Now, what blend of the old and new—the traditional ways that made the company successful, the novel technologies and methods that propel future growth—could help metal fabrication’s next generation succeed?

Next-generation Tech

At FABTECH 2015 I ran into John Axelberg, president of General Stamping & Metalworks, a large contract metal fabricator in South Bend, Ind. He was just weeks away from opening a new plant with a novel design: a factory with a front office surrounded on three sides by a U-shaped shop floor, and a wall of windows in between. He told me that when people start their day, everyone—sales, engineering, laser cutting machine operators, welders, grinders, fork truck drivers—walk into the plant through the same doors.

“We recognized that we needed to create opportunities to communicate,” Axelberg said. “So one of the easiest ways to do that is to bring everybody in the company through the same front door. We have no separate doors for office workers and shop floor employees. Having one door creates opportunities for conversations.”

In many ways, FABTECH provides that “one door” for the industry where everyone, from top managers to rookie machine operators, can meet to discuss ideas and discover what could take their operations to the next level.

Communication undergirds the ideas behind Industry 4.0, where production becomes autonomous and everyone works to handle not the convention but the exceptions, the oddball jobs that require special attention.

Not only could factories become partially autonomous, but so could entire supply chains. To get there will require continual communication in what at FABTECH 2015 speaker Karen Kerr, senior managing director for advanced manufacturing at GE Ventures, described as the digital thread. “We connect machines in our factories. We now need to build an industrial cloud, collect data from machines, and perform a deep analysis. And we’re creating a digital thread to communicate with customers and supply chain partners.” The goal is to ensure everyone can “work from one single version of the truth.”

The pandemic put such concepts to the test. Regardless of how transparent two supply chain partners are, their physical location matters. Reshoring opportunities abound, which in turn are pushing metal fabricators to ramp up capacity as quickly as practical.

How metal fabricators go about this depends on the industry they serve and the mix of products they make. Structural fabricators are more automated than ever, using beam lines to cut, drill, cope, and scribe layout marks. Beams then make their way downstream not by bridge crane, but by roller conveyor to welding cells, more of which are becoming increasingly robotized.

Heavy plate fabricators are making similar use of automation, reducing the need for bridge cranes, and relying on heavy-duty conveyance devices to send large workpieces to the next stage of production, be it a large press brake, a plate roll, or anything else. Even for the largest industrial fabrications, it’s all about flow.

The same goes for the sheet metal arena. And the technology to attain that flow has changed dramatically, especially within the past few years. The FABTECHs of the mid-2000s had a smattering of fiber lasers. Now they dominate the show floor and are making fabricators rethink how products flow.

Several strategies have evolved in recent years. One considers the fact that a single ultrahigh-powered fiber laser can do the work of several lower-powered machines. So, in this scenario, one or a handful of blanking machines feed downstream bending operations involving more than just your conventional hydraulic press brake. Some parts flow to a panel bender or folder; others to automatic tool change press brakes, some automated and others manually fed.

Another strategy involves the combination of processes, especially cutting and bending. Flexible manufacturing systems have been available for years, of course. Material emerges from an automated storage and retrieval system and is punched and sheared before moving on to a panel bending system. Some customized systems have connected directly to automated welding.

At the most recent FABTECHs, more have talked not about cutting or bending as separate processes, but about the combined “cut-bend cycle.” In some of the latest automated systems, laser cutting and bending occur in a symbiotic way, both being connected to a centralized system that stores raw stock and serves as a work-in-process buffer.

Regardless of the automation strategy, the need for humans hasn’t waned; a human can perform bending operations (especially those involving highly disparate product mixes) that a robot simply can’t do.

In a broader sense, though, the old conversation about what a human can do versus automation misses the larger point: Metal fabrication (and manufacturing overall) isn’t a battle between machines versus manual labor; it’s a quest to find the best way to make something, with everyone within the fabrication organization, from top management to the front lines, asking, How can technology help?

Several exhibitors at FABTECH 2019 showed applications in which robots—through reading information from the part design file, using vision and so-called “digital twin” technology, or via other means—effectively program themselves. Exhibitors also showed technology that could help create fixtureless setups for welding robots. They travel on overhead gantries, scan the work below, and start welding. Other technology showed laser scanners that projected outlines of where parts for one particularly large weldment could go, guiding manual welders to tack massive workpieces before they were sent into a robotic welding system.

“It used to be about the knowledge of the tribe. Now it’s science.”

So said Michael Walton, manufacturing industry solutions executive at Microsoft, during a talk at the 2019 show. Walton leads Microsoft’s efforts in cloud-based machine learning and artificial intelligence. “Many think such technology is only for the big guys, but it’s just not true.”

This is largely thanks to two elements: First, AI often uses cloud computing performed off-site and offered as a service; second, sensor technology has come a long way.

New approaches to robotics and automation now work from the AI-based intelligence Walton described, and FABTECH 2019 showed the technology only in its infancy. Just imagine what has transpired during the past two years, and just think of the progress to come.

A Shining Light of Opportunity

The industry needs more people who do such imagining. In an economy where the best and brightest go to college, dig themselves into debt, then spend years stumbling to find a solid footing for their lives, FABTECH represents a shining light of opportunity. As the economy emerges from the pandemic, so many millennials and Gen Zers are still stumbling. They might be digital natives, but they know next to nothing about sheet metal or manufacturing in general.

Think about the vast range of technology FABTECH displays, from laser cutting to plasma cutting, punching, stamping, welding, and finishing of sheet metal, plate, and tube and pipe. Each process has a full range of operational options, from manual to fully mechanized and robotized. Today the industry remains in desperate need of people who can think in new and creative ways about all the technological alternatives. It’s difficult to ask How can this technology help? if you don’t understand or fully appreciate the technology’s implications.

It’s-the-way-we’ve-always-done-it inertia can be a fabricator’s Achilles’ heel, and new talent can help a fabricator break that inertia. They do it by marrying their knowledge rooted in metal fabrication fundamentals with technological innovation. They know not to disregard the craftsmanship that has made fabricators successful, but instead to use technology to propel the craft to new levels of efficiency and productivity.

Manufacturing is not about technology versus people; it’s about technology and people. And more than anywhere else in metal fabrication, FABTECH has become where technology and people come together.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI