Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Newly launched fabricator tackles the quick-turn market

Automated order processing is key

- By Tim Heston

- June 2, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

A dinosaur model illustrates SendCutSend’s precision cutting. Formally launched earlier this year, the shop aims to serve an underserved market, including those that might not have considered laser cutting before.

Jim Belosic has been self-employed for years, but unlike many entrepreneurs in metal fabrication, his professional life until now hasn’t focused on fabricating parts and welded assemblies. He’s always had a passion for making things; if he wasn’t working, he often could be found in his garage with a welding torch.

But Belosic’s day job was in software. In the early 2000s he spent most of his day sitting at the kitchen table with his laptop, doing web design and small software projects. “And when clients asked for more, being broke and hungry, if they needed some kind of crazy software for their website, I’d always say yes and then try to figure it out.”

Over time Belosic’s software business, ShortStack, delved into sophisticated marketing software platforms that included data analytics. “Growing the software business has been great,” he said, “but my passion always has been working with my hands, including welding. We have a group of engineers here who are all into motorcycles, cars, robotics—all fun hobby stuff. And we all have a shared hobby space, a 5,000-square-foot shop, where we do stuff on breaks and weekends.”

The projects got serious enough that they often needed sheet metal cut to specific sizes and shapes. “But it was very difficult for us to find a supplier that was willing to make us just one or a handful of parts at a reasonable price,” Belosic said.

From there Belosic and his team could have just purchased a small plasma cutter for the small-shop or hobbyist market and continued on with their weekend projects—but being entrepreneurs, they thought differently. Surely they weren’t the only ones who had a hard time getting parts. Could a laser cutting shop be designed specifically to serve this underserved market? Launching Reno, Nev.-based SendCutSend in February of this year, Belosic and his team of a half-dozen decided to give it a shot.

The Conundrum of the Long Tail

Many custom metal fabricators aim to serve the total product life cycle. A prospect comes in with an idea and the fabricator helps design the part. It makes a prototype, then a few more, then ramps up to low-volume production. If the fab shop has stamping capability, it might decide to build a tool to ramp up production even more. As the product matures, production continues until the product becomes out-of-date. A newer version is developed, but the old product still needs parts; and the fab shop can provide those too, decreasing volumes to produce repair and aftermarket parts.

Fabricators certainly can produce lot sizes of one, but the real growth comes from those larger blanket orders. Individual order sizes might be small—hence the need for flexible and soft tooling along with quick changeovers—but fabricators want to grow a customer relationship so that those small orders keep coming throughout the year.

All this often creates some high revenue concentrations. According to the “2018 Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey” from the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, on average a fabricator’s top four customers make up more than half of a shop’s overall revenue, and that average hasn’t changed much from year to year. Map out the revenue mix at a typical fabricator and you’ll often find a few big customers along with a long tail of smaller clients.

Traditionally, it’s been tough to grow a business in a big way without those larger clients, mainly because of the quoting process and order-processing time. Lasers are made for the high-product-mix world, but it still takes time to submit and review bids, program the order, develop the nest layout, and send it to the shop.

But what if that order process were automated entirely? What if someone could order a sheet metal part over the web and within minutes—and with no human intervention—those parts appeared on a nest, ready to be cut, sorted, and delivered? That would allow a fabricator to focus on that “long tail,” and even extend the tail further to capture other potential customers—be they home project DIYers or hobbyists or entrepreneurs or engineers—who wouldn’t have considered custom laser cutting as an option. That was the idea behind SendCutSend.

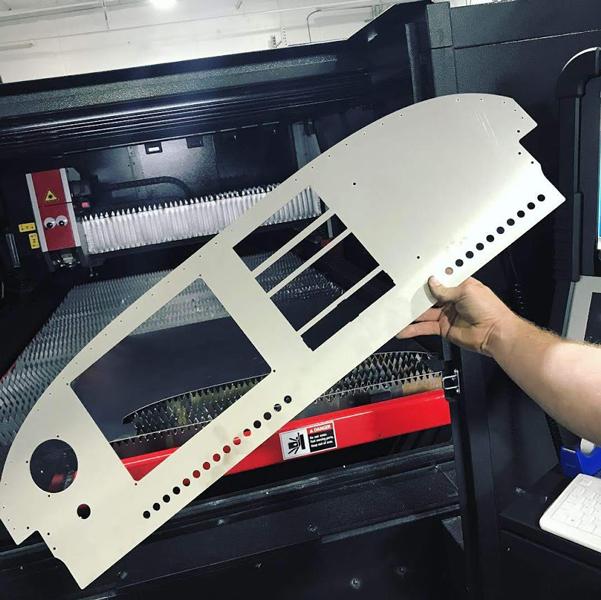

A part is lifted from a nest after cutting. The company is already looking for ways to automate the denesting process.

The concept of automated order processing isn’t completely new. Europe has fabricators like Netherlands-based 247 TailorSteel, which has dozens of lasers and automatic-tool-change press brakes. It specializes in cutting and bending, not welding or other value-added services. Still, the fabricator has thousands of customers who submit low-quantity orders online and receive parts (or just one part) in a day or two or three.

Although it isn’t entirely absent, automated order processing hasn’t proliferated in the U.S. Part of the reason might be that fabricators are taking on more value-added processes, like machining, powder coating, welding, and assembly. The more manufacturing steps a fabricator does, the more complicated quoting and order processing become.

SendCutSend launched formally in February 2019 as a shop dedicated to laser cutting, and the key to the new launch has been that automated order processing.

The company’s quoting started with a so-called “bounding box” approach. If the job fit in a certain size box, the job would be a flat rate. “However, that pricing wasn’t always fair to customers who had very simple parts that can run quickly on the laser,” Belosic said, “so we’ve moved to a new quoting method using algorithms created in-house. The pricing accounts for material cost, cut time, nesting, part sorting, consumable usage, handling, and shipping.”

The company has assisted customers who don’t have design files, sometimes creating a CAD drawing from a napkin sketch if needed. But if customers have design files ready to go, they can upload them to the website, see a preview, select a material and thickness, then receive an instant quote. If the file passes some preflight tests (described later), the job is sent to the laser; within four to eight hours, it’s cut, packaged, and shipped.

The company “soft launched” into a beta phase last year (the company founders carried over some of the software jargon). “We started outsourcing some of the production just during our beta phase, for a few months, just as a proof of concept,” Belosic said. “But it was so painful to outsource. We were all about quick-turn, and outsourcing just took too long. We quickly realized that outsourcing was not going to be the road for us. We needed to have laser cutting in-house so we could control our turnaround time. Our software was able to process files within seconds and have it ready for the laser, but then we had the logistics issues [associated with outsourcing].”

So in September 2018, still in its beta phase, the company installed its first laser, an Amada fiber laser. Right at launch the company went with a new laser. “We’re all about quick-turn. We wanted the service and warranty,” Belosic said. “We knew that if we were down for any amount of time, it would be extremely costly.”

Preflighting the Nest

The operation isn’t your typical startup. This becomes abundantly clear when you dissect how exactly parts reach the laser. SendCutSend uses an off-the-shelf nesting engine, but it also uses that nesting software coupled with its own custom software.

As Belosic explained, much of the custom software deals with preflighting: checking the drawing files for open contours, ensuring profile geometries are correct, and performing some preliminary nesting. When a nest gets to the off-the-shelf nesting software, the software essentially places what it receives in the predetermined nest layout, then postprocesses it to the numerical control. Why does the nesting software require a preflight system? It has to do with what could be the key to SendCutSend’s entire business model: “Our big goal is to have that direct job flow between the web interface to the [laser cutting machine],” Belosic said. “We go from the customer directly to the material.”

Using off-the-shelf nesting software alone, the shop still would need to batch files, choosing specific jobs manually to populate specific jobs on specific sheets.

Immediately after denesting, pieces are bound and packed in a shipping box with the label already affixed.

“But we knew how time-consuming that could be,” Belosic said. “We didn’t want to have guys dedicated to dragging and dropping orders into the nesting software all day. So instead we have our website prenest on the back end, gathering all customer jobs by material and thickness.” All the off-the-shelf nesting software does “is essentially listen to commands [from the website prenesting system], and then, once a sheet hits a certain density, outputting it to the machine.”

Belosic added that remnant management is another critical factor. Because SendCutSend wants to turn around jobs as quickly as it can, it can’t always wait until it receives enough orders to fill an entire sheet of a particular material grade. To meet the day’s shipping deadline, in fact, orders need to be nested by 1 p.m. This in turn requires smart remnant management—storing and organizing sheets and ensuring the remnant pieces remain available in the nesting system.

Tabbing and Polishing

What about small parts microtabbed into the sheet? This again is where strategic nesting comes into play. Belosic said that the team doesn’t want operators spending their days breaking tabs and deburring parts. So if a customer orders a series of small parts in gauge material, the system nests and tabs these parts together, and the operator then lifts the microtabbed section out and places the entire piece in a mailer.

He added that for low-volume orders, this isn’t a problem. And if customers can receive their parts in just a day or two, breaking tabbed parts out on their own is a small price to pay.

Customers are also willing to spend a little time putting a final polish on a laser-cut part. “As soon as something is cosmetically critical, we found that everything comes to a grinding halt,” Belosic said. “Half of them don’t pass quality control because of a minor scratch. So we’ve been communicating with customers. We tell them it’s a manufacturing environment, and if it’s cosmetically critical, it might be best to do the final polishing at your location.”

This has worked especially well for the company’s jewelry customers. The company cuts small parts, often in copper and brass, perhaps even tabs them together. They might have ever-so-minor scratches on them too. But the jewelers receive their parts very quickly—and again, a little tab-breaking and polishing is a small price to pay.

A Vision for Denesting

The prenesting software also plays a key role in denesting. When sorting, an operator refers to an image of the nest on a screen, and overlaid on each part is a job number. The operator refers to the screen, lifts the piece out of the nest, and puts it in the bin or bubble mailer already affixed with the packing label.

“Our accuracy rate for this is very high,” Belosic said, “but it’s still too manual for me. So we’re working on a vision system where we’re using robotic image matching,” using the computational power of Amazon Web Services. At this writing, it isn’t ready for prime time, but if the project meets its goals, it could give SendCutSend a technological edge.

As Belosic explained, “This uses a system from Amazon that does facial recognition, except we’re training the robot differently. Instead of recognizing faces, it’s recognizing parts. So from the customer’s drawing, the robot knows that the part is a rectangle in a hole. The robot can look for a rectangle in a hole, grip it, and put it in a bin. That’s going to be the next lights-out portion of the operation.”

Tests are still ongoing, and technical hurdles remain. For instance, the fiber laser’s kerf width is extremely narrow, which presents a challenge for a vision system attempting to detect a part outline, particularly if the part lies absolutely flat in the cut sheet. But the shop is experimenting with other methods too, including the integration of an inkjet printer to identify parts after they emerge from the cutting work envelope.

SendCutSend founder/President Jim Belosic (left) shows a cut part he removed from a nest. Jobs involving one piece are common.

Quick-Turn Opportunity

Since its beta launch last year, SendCutSend has processed orders from more than 800 separate customers.

And what’s the average lot size of those orders? According to Belosic, just one piece. “Every once in a while we’ll have a customer who wants several hundred of something. But in reality, we’re accessing a lot of customers who are new to sheet metal and new to laser cutting.”Since the soft launch last year, the shop has fine-tuned its material purchasing strategy, keeping stock of common material (aluminum, stainless, cold rolled, hot rolled pickled and oiled, copper, and brass) and can special-request materials from local suppliers.

At this writing the company is focusing on laser cutting only. That said, Belosic and his team aren’t ruling out the possibility of adding other equipment, like press brakes, down the road.

He added that the company does have the capacity to produce larger volumes. After a day of cutting nests dense with disparate parts, the company has scheduled larger-volume orders—such as thousands of pieces—in the evening.

“Whether we’re doing one or a thousand parts, there’s huge opportunity in extremely rapid job turnarounds,” Belosic said. “That’s where I see us scaling up. And we have long-term plans of additional locations. We’d like to be bicoastal. The idea is, if we can give you the parts that you want within one or two days, there are just huge opportunities there.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI