Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Reflecting on FABTECH's record-breaking 2019

Automation and digital manufacturing dominated the metal fabrication industry’s main event

- By Tim Heston

- January 13, 2020

- Article

- Shop Management

Despite the weather, FABTECH 2019 broke records, with nearly 49,000 people walking the halls of Chicago’s McCormick Place.

Early November weather wasn’t kind to Chicagoans, who endured snow, sleet, and single-digit temperatures. The mess arrived Nov. 11, just in time for FABTECH®, North America’s largest industry event, which began just as the flight cancellations that day mounted. Would the weather, combined with news of a softening global economy, keep people away?

Not at all. Despite the weather, the 2019 event closed with record attendance of 48,278 attendees, a 7% increase over the previous Chicago FABTECH two years ago. What exactly drew so many through the cold, snow, and economic uncertainty?

Gregg Simpson, owner of Ohio Laser, a custom fabricator near Columbus, Ohio, summed it up this way: “People are here, and they’re interested in buying. Everyone I’ve spoken to all week says the same thing. ‘We don’t see anything going on out there that’s going to slow us down.’ They’ve also been telling me that work has been coming back from overseas, and it’s the kind of work they haven’t seen in years.”

Simpson and others at the show did say that the election and dysfunctional politics in Washington are concerning, and uncertainty still reigns around trade and tariffs. But one concern dominates: finding people—not just skilled people, but any people.

As Joe Vidmar, president/CEO of AOC Metal Works, a growing, multiplant contract fabricator and stamper based in Lawrenceburg, Tenn., explained, “We’re having a good year. The top line is growing and the bottom line is growing. But we’re regulating our growth based on our ability to attract and retain people. And then, how do we automate to make them as productive as possible?”

Robotics and automation dominated the show, even more so than in previous years. With record-low unemployment, fabricators large and small no longer strategize whether they will automate, but when and how.

Automation for All

“Visualize. Describe. Direct.” So said Michael Walton, industry solutions executive at Microsoft, at the show’s FABx Tech Talks, inspired by the popular TED Talks. “Historically, those three words—visualize, describe, and direct—have been very important to our military professionals,” Walton said. It was an apt observation made on the show’s opening day, which fell on Veterans Day.

Walton leads Microsoft’s efforts in cloud-based machine learning and artificial intelligence. “Many think such technology is only for the big guys,” he said, “but it’s just not true.”

This is largely thanks to two elements: First, AI often uses cloud computing, which is performed off-site and is offered as a service; second, sensor technology has come a long way, and prices have fallen dramatically. Walton described job shops that purchase sensors that cost less than $50. “Sensors with a magnetic backing on them can be placed on a fabrication machine, regardless of the brand or age, and through detecting vibrations, these sensors can record when that machine is cycling and when it isn’t.”

Walton described a visit to a small galvanizing shop. Until recently it relied on its veteran employees to achieve a consistent coating. Now, using inexpensive sensors and cameras, the company can actually see how the zinc particles adhere to the material surface, and through that they discovered how to achieve complete, consistent coverage and ultimately save more than $1.2 million. Walton said that AI allowed this small shop to visualize—to see the process in its entirety—describe that process fully, then direct toward improvement.

A robotic bending system from Bystronic features automated robot programming and the ability to remove the robot for manual operation.

“It used to be about the knowledge of the tribe,” he said. “Now, it’s science.”

Walton added that there’s nothing inherently wrong with the “tribe.” After all, tribal knowledge built much of modern manufacturing. Many successful manufacturing careers have been built on such knowledge, gained through years of experience on a single machine or process.

But modern manufacturing, with its minimal inventory and kit-based (as opposed to batch) part flow, demands cross training and flexibility. Few spend years doing a single process over and over and over, so that tribal knowledge never has a chance to develop the way it has in the past.

Enter automation and, especially, autonomous operation, where machines with AI manage all by themselves to keep processes stable. If AI and machine learning development continues on its current trajectory, the future fab shop worker will experience a very different reality, reflected by many emerging technologies at the show.

Consider Omni Robotic, a company offering robotics driven not by a written program but by AI. Available now for powder coating and other surface prep robotic units, the system effectively allows robots to teach themselves.

Cameras view a part entering a powder coating booth and create a “digital twin” on-the-fly. From that the robot can “learn” to paint the part and ensure complete coverage. Sequencing and product mix are inconsequential. The robot isn’t using a previously drawn solid model, but instead a digital scan of the actual part it’s about to coat. The data from AI feeds directly into the robot controller.

“We’re targeting all surface treatment processes,” said Sam Gerges, business development manager, “including blasting, shot peening, painting, and powder coating.”

The company has yet to tackle processes in which the robot or other automation needs to apply pressure, and it hasn’t yet offered technology for other robotics applications in the fab shop like bending and welding. Regardless, the technology might hint at how AI could drive robotics applications in the future.

You’re Automating What?

The latest FABTECH revealed just how far automation has penetrated every aspect of the industry, even in the heaviest of fabrications. For instance, Pemamek introduced its large-scale welding automation platform designed for high-product-mix operations. Every weldment can be completely different from the next.

Picture a large-scale gantry that travels over a massive panel assembly destined for a ship. “You lay out the parts in any orientation you’d like, and the system’s laser scanner scans it,” said Michael Bell, the company’s North American sales manager. “You snap your welds with your mouse on the image, draw where you want the weld to go, and the robot finds it and welds it.”

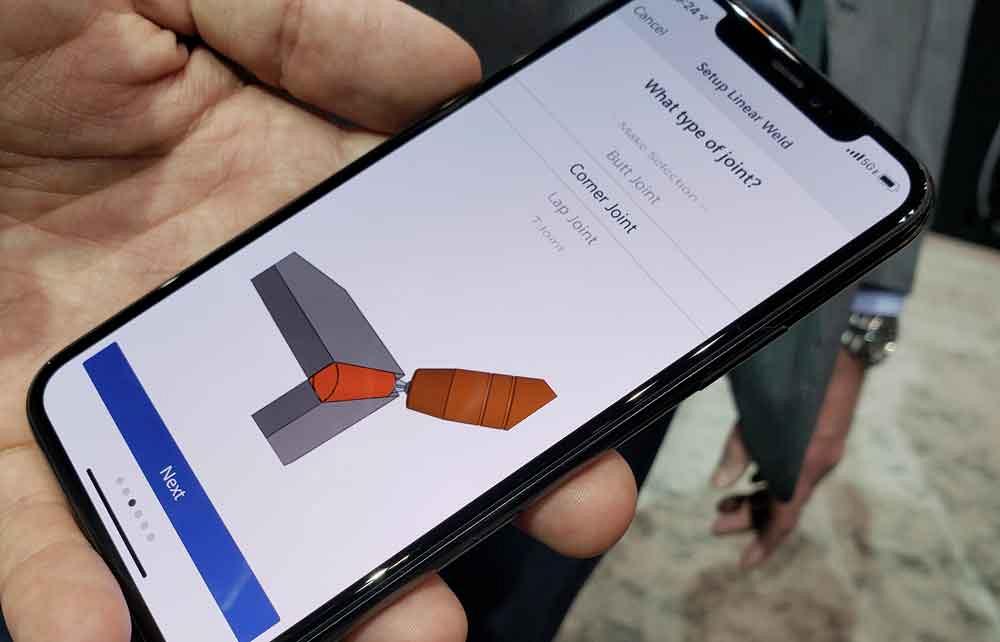

Hirebotics, in collaboration with Universal Robots and Red-D-Arc, introduced a welding cobot that can be programmed using a phone app.

Matt Jurczyszyn, vice president, KUKA Industries, Clinton Township, Mich., has experience with high-product-mix, heavy-duty welding automation too. At the booth he recalled one large fabricator that needed to weld the floors of garbage trucks. The manufacturer has 27 varieties of trucks, each with different floor components. One usually would think the job to be far too heavy and complicated for automation. After all, just think of the fixturing that traditionally would be required for all those massive floor sections.

Thing is, automation engineers found a way to prepare the assembly without individual fixtures, thanks to a laser system that projects an outline of where parts go for specific floors. “The system pulls from 27 different floors, depending on the model you’re working on,” Jurczyszyn explained.

Instead of loading and tacking parts into a hard fixture, operators align parts with a laser outline projected from above. They tack them in place, then send the 25-plus-foot-long floors into a robotic welding system.

Collaborating With Robots

Many hesitate to take the plunge into robotic automation, often because of space constraints and concerns about flexibility and reliability. A part might almost fit a robot’s ability, but not quite. Or a product could be partially automated, then finished by a nearby technician. Problem is, it’s unsafe for anyone to work alongside a conventional robot. You need space for fencing, doors, and light curtains.

Here’s where collaborative robots are filling a need, and they were everywhere at FABTECH. Nearly every major robot manufacturer—Yaskawa, FANUC, KUKA, ABB, and more—had them on display.

Integrator Hirebotics showcased a Universal Robots welding cell, developed in partnership with Red-D-Arc, an Airgas Co., that can be controlled via a phone app, using cloud-based weld procedures. Hirebotics offers robotic cells, welding and otherwise, on a rental basis—a kind of robotic “temp,” hired when needed and paid for based on hours of use.

Demonstrating the collaborative welding cell, Hirebotics CEO Rob Goldiez showed how an operator can choose weld parameters using visual cues and even simple process simulations. “The animation shows the operator exactly what we’re doing,” Goldiez said, hence preventing miscommunication from language barriers or different uses of certain terms.

Collaborative robots can “sense” the world around them, thereby allowing people to work right next to them safely. Conventional cobots do this through their ability to “give” if blocked, be it by a human extremity or anything else.

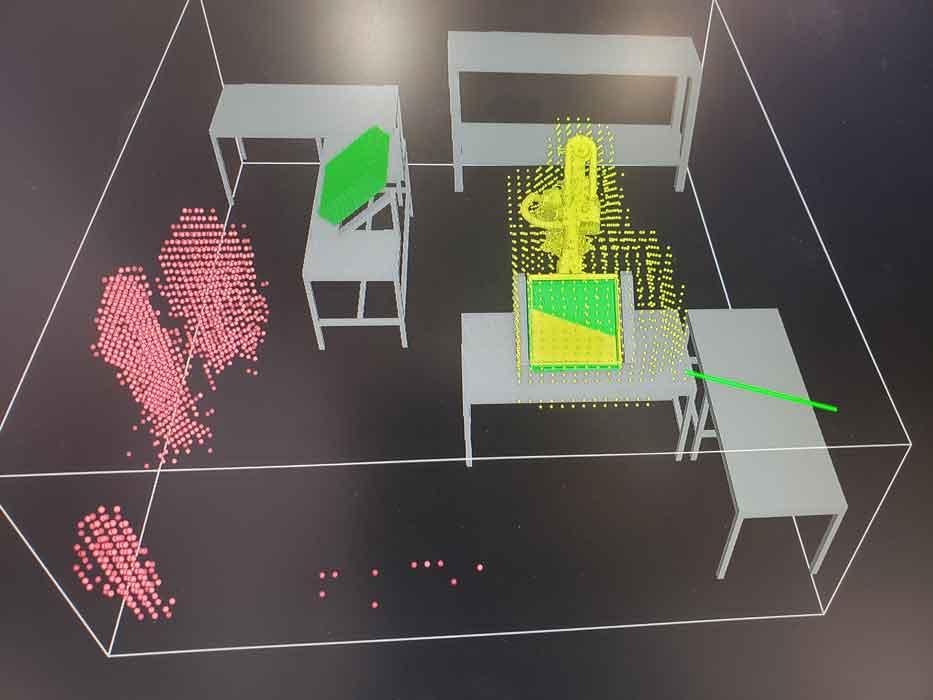

But another automated cell on the show floor had no physical guarding or conventional optoelectronic devices, and yet it had a typical articulating-arm robot that, under normal circumstances, couldn’t run safely without guarding. But there it was, running in a collaborative setup, with people walking right alongside it. Surrounding this cell were several cameras that scanned the area and created a “point cloud” around a conventional robot manipulating a heavy object. The main attraction at Veo Robotics’ booth, those cameras effectively made a conventional robot a collaborative one.

Patrick Sobalvarro, president and co-founder, said Veo has worked closely with ISO and the Robotic Industries Association on safety standards. The cameras don’t use machine learning, which is based on statistical models that aren’t encouraged by ISO safety committees.

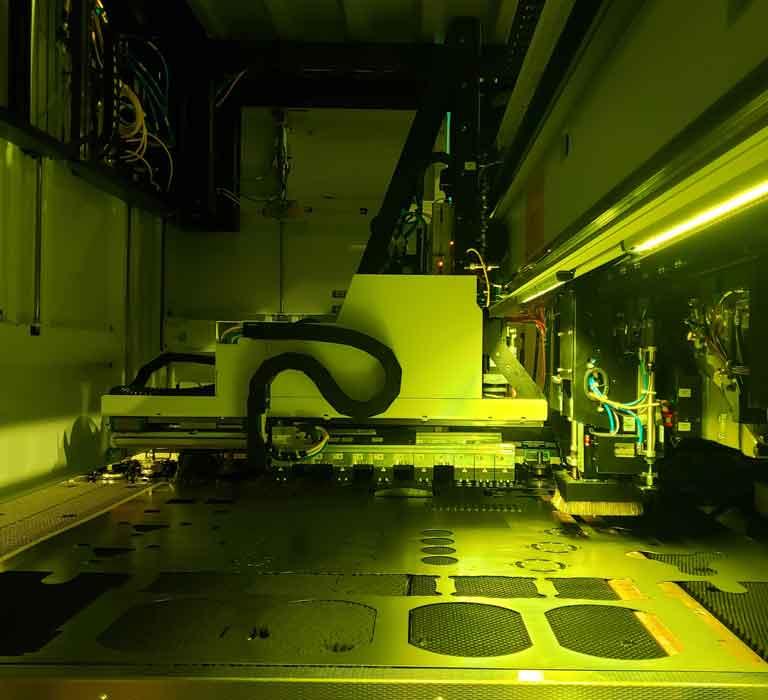

Part removal automation dominated the show. Here, cut parts are removed from a TRUMPF punch/laser combination machine.

“Everything is dual channel,” he said. “And we’ve taken a conservative approach to how the safety system works. We don’t try to positively identify humans. We identify things we know, including the workpiece and fixtures. Anything else and the robot stops.”

Sobalvarro added that the company’s long-term vision is for a distributed version of the system that could cover an entire factory floor. “Then it becomes more like a utility, such as network connectivity or compressed air. It’s just something that’s always there.”

Streamlining the Cut-Bend Cycle

Cutting and bending technology on display at FABTECH reflected an industry with a renewed focus on automation. Machine vendors continue to work to make laser cutting more reliable and consistent than ever. Amada had its North American release of a laser that manipulates the beam in specific patterns tailored for specific needs, including a kerf mode, designed to cut in a way that makes part removal automation more consistent.

TRUMPF introduced its Active Speed Control that adjusts cutting parameters in real time to accommodate actual sheet surface conditions, including rust and residue left by stickers. It also introduced its tracing system that helps track parts as they travel the factory floor, revealing exactly when and where parts halt in a bottleneck.

Bystronic introduced its fiber lasers with beam-shaping technology, along with a small electric brake with a robot that takes a 3D model and effectively programs itself, running a slow “dry run” for the first part before bending at full speed for subsequent parts. LVD demonstrated its robot bending cell that generates a bend program automatically, runs a simulation, automates the robot program, and starts bending shortly thereafter.

Mazak Optonics Corp. and Prima Power introduced 10-kW fiber lasers. Salvagnini showed its adaptive fiber laser, which adjusts laser parameters on-the-fly based on part geometry, a similarly adaptive panel bender, and a press brake with automated tool change. MC Machinery Systems introduced its own automatic tool change press brake, and like others, automation front and center, especially when it comes to part sorting. Many machine vendors have modular configurations so systems can be added to over time.

Judging by the technology at the show, fewer shops are thinking only about laser cutting speed or punch hits per minute. Years ago a cutting-only shop could make a go of it and grow quickly. Now, adding value beyond cutting is almost taken for granted. So it’s no surprise that cutting systems at the show were designed with bending in mind, with parts being automatically stacked or otherwise delivered directly to press brakes, panel benders, folders, forming presses, and elsewhere downstream.

In this sense, the manufacturing steps of fabrication are being thought of in a broader context. It’s no longer the “cutting” process; it’s the “cut-bend” process. Cutting and punching a part, achieving the highest material yield practical while maintaining minimal work-in-process after cutting, is just half the battle. The other half involves organizing and presenting the cut part to the next process. It’s little wonder FABTECH had more part takeout and stacking automation than ever before. After all, a cut blank isn’t truly complete until the next operation can do something with it.

The Factory of the (Near) Future

Taken together, the booths at FABTECH, showcasing technology from more than 1,700 exhibitors, hinted at the industry’s future—and it’s sure to be a connected one. Lincoln, Miller, ESAB, Fronius, and others touted weld data management and the use of the cloud to make a welding department more productive. Vendors of cutting and bending machines, along with a handful of third-party players, touted their ability to connect and monitor machines remotely, catching problems before they occur.

The show even hinted at a future of materials processing. This included additive manufacturing, of course. The show’s Additive Manufacturing Pavilion presented some eye-opening capabilities, including a large-scale laser additive process that uses a unique three-beam head from Laser Mech® integrated into a system from Midwest Engineered Systems Inc. (MWES).

At Omni Robotic’s booth, an AI-driven system scans the part in front of it (in this case, the “part” is a show attendee) and creates a digital twin, which it uses to create a robot program automatically.

MWES exhibited a massive blade structure that took several days to print. That’s a long cycle time when you compare it to a casting process, but it’s no time at all when you realize that the casting (of unusual material) has lead times from overseas suppliers spanning months or even a year or longer.

Near the back of the show floor, an area of startups and other firms with small marketing budgets, was one company touting nanotechnology. It’s a niche that received a lot of press attention 10 to 20 years ago, though not as much recently, but the field hasn’t gone dormant.

That startup in the far-back booth was MetaLi. Launched out of work from UCLA, the company has introduced nanomaterial-infused metal. At present it’s focusing on welding consumables that can weld material that would previously crack during cooling. The material MetaLi has created is effectively “engineered” with nano-sized ceramics that control the material grain to meet a certain need, be it welding or, perhaps in the future, stamping, bending, and various types of thermal cutting, from oxyfuel to the laser.

Considering this, imagine a fab shop with an inventory of nano-engineered materials, each tailored to undergo specific cutting, forming, and welding operations. For years machine-makers have worked to make their machines adaptable to material variability. Engineered material would make fabrication that much more reliable.

Also imagine, if you will, a connected, automated shop. Predictive maintenance, managed by sensors and cloud connectivity, is taken for granted, just one more utility like the electric and water. So is safeguarding, with a virtual “point-cloud curtain” surrounding every hazardous robot and machine. This frees robots from their cells, allows everyone to work alongside them, and makes shop floor layout more flexible than ever. AI rules robot and machine programming. Like their human predecessors, robots “look” at parts and decide for themselves the best way to bend, weld, and coat them.

Even so, the tribal knowledge remains; after all, the knowledge of a fabricator’s “tribe” sets it apart from the competition. But the knowledge will be applied differently. Those with detailed process knowledge will be more valuable than ever, but they won’t use it to cut, bend, or weld part after part after part. They’ll instead use that knowledge to communicate best practices and make better use of automated systems.

Process ignorance could become more dangerous than ever, considering how quickly modern machines produce, and how rapidly disruptive technologies mature. The industry’s rapid adoption of the fiber laser is an apt example. An ignorant operator can produce a lot of bad parts in a hurry. Yes, the future shop floor might look utterly different, but sheet metal fabrication fundamentals—rooted in physics, thermodynamics, and geometry—aren’t likely to change.

At the same time, the most successful also will learn to adapt and embrace structural and technological disruption. During his presentation at the FABTECH conference, David Tweedt, president of Win Enterprises, an industry consulting firm, showed a video of a new kind of boat-building that uses, of all things, 3D printing. The result of a project spearheaded by the University of Maine, a massive printer produced a complete patrol boat in just 72 hours. Conventional fabrication would have taken months.

“Yes, you can see that [the printed boat] is ugly, and it’s not ready for prime time,” Tweedt said. “But how long do you think it will take for industry to refine this, when it will be able to utterly disrupt the boat-building business?” He added that in the modern economy, “we have structural and technological disruption, and it’s not limited to a single industry. It’s not a matter of if your industry will be disrupted. It’s a matter of when.”

“What Can We Do?”

On the final day of the show, a 20-year-old welding engineering student from LeTourneau University stood during a panel discussion on skilled labor and asked an inspiring question. “What can we, as young people who will soon be entering the workforce, do to ensure that we’re not attending the same kind of panel discussion in 20 years?”

A robot in Veo Robotics’ booth was protected by a virtual “point cloud” curtain. The red dots represent nearby attendees observing the operation

A moment of silence followed, then a rush of applause. It was as if audience members were giving a collective sigh and gaining a glimmer of hope. They were so happy to hear a 20-year-old ask such a question.

The panelists gave some timeless advice. Be engaged but humble. Don’t expect revolutionary change overnight. But over the next 20 years, that welding engineering student might see the pace of change in manufacturing accelerate faster than ever.

The industry must draw a new kind of worker, one who grew up with software and automation but also has a passion for making things—and, not least, for uncovering the increasingly sophisticated ways new types of fabrication processes and automation can help.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI