- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The unsung hero of fluid and bulk solids delivery

Loading arms from designer, fabricator, and OEM provide vital connection for moving freight

- By Eric Lundin

- July 7, 2020

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

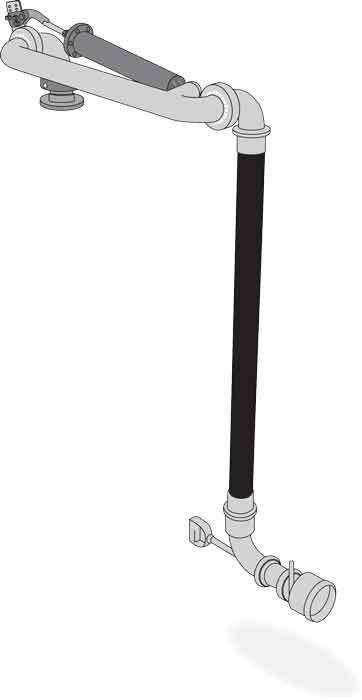

Somewhere among that colossal amount of metal—the innumerable tons of steel that make up the rig or the platform, the vast amount of tube and pipe, and the tremendous number of valves and couplings—is a small subsystem, one made up of about 400 lbs. of steel, that provides a vital connection: a loading arm. That's the forte of OEM and fabricator Excel Loading Systems.

You don’t have to specialize in the petroleum industry to visualize some of the equipment used to take oil from raw material to a finished product, such as gasoline. Oil rigs and oil platforms, ocean-going tankers, refineries, pipelines, and tanker trucks are among the most visible elements in a system that nearly all of us rely on every day—a system that pumps oil from the ground, transports it, refines it, and delivers it to any of the 168,000 gas stations in the U.S.

Somewhere among that colossal amount of metal—the innumerable tons of steel that make up the rig or the platform, the vast amount of tube and pipe, and the tremendous number of valves and couplings—is a small subsystem, one made up of about 400 lbs. of steel, that provides a vital connection.

That subsystem is a loading arm, a device that is the forte of designer, fabricator, and OEM Excel Loading Systems, Sharonville, Ohio.

Load ‘em Up!

A loading arm usually comprises two or three of lengths of pipe that end in 90-degree elbows. Each end is joined to the next tube by a swivel, a mechanical device that can rotate 360 degrees and still contain the media. One end of the unit is fastened to a storage container or a tank, and the other end has a coupler that attaches to a port for emptying a railcar or a tank. When a railcar or tanker truck stops to unload its cargo, a depot operator swings the loading arm into position, fastens it to the unloading port, and opens a valve.

“Our three most common applications are railcars, tanker trucks, and totes,” said David Shull, president. About 90% of the company’s products are designed for railcars and tanker trucks. Loading systems for totes, chemical mixing vessels that measure 48 in. by 48 in. by 48 in., constitute about 10% of the company’s business. Most of the applications involve liquids, although some bulk solids also are conveyed by loading arms.

“Standard loading arms measure from 2 in. dia. to 6 in. dia.,” said Joe Williamson, director of engineering. “The specific diameter depends on the required throughput.”

Excel’s loading arms come in two broad varieties: fixed-length and variable-length. For rail applications, and truck applications in which truck positioning is accurate and consistent, the simpler, fixed-length type—the one with the fewest components and, most importantly, the fewest bends—is appropriate. For applications in which positioning the transport vessel isn’t solidly consistent, the variable-length style is the best choice.

Building a Loading Arm

Excel’s raw materials include carbon steels, stainless steels, and for handling aggressive chemicals, specialty metals such as alloy 20 and Hastelloy metals. The company purchases lengths of tube and matching 90-degree elbows. For food-grade applications, it purchases tube that has the ID polished to the necessary smoothness, specified in average roughness (Ra).

After getting cut to length on a band saw, the arm component is joined to an elbow.

“We utilize both TIG welding and MIG welding for our applications,” Williamson said. "For all loading arm applications, we weld to a governing standard, such as ASME B31.3 Section VIII.

In addition to top loading and bottom loading styles (bottom loading is shown here), loading arms come in several varieties, including fixed reach, variable reach, supported boom, unsupported boom, and counterweighted.

“For our food-grade loading arms, the final fabrication step is a polishing of the weld zone,” he said. “We use a manual tool that has enough flexibility to handle the 90-degree bend, polishing the IDs of pipe sizes that are 3 to 4 in.,” Williamson said. The company uses roughness gauges to determine the smoothness, and when the weld bead is smooth enough, the arm goes to an assembly step for attaching the swivel joints and other hardware. Then it’s ready to ship.

Nearly Endless Versatility. For some applications, the arm and options are straightforward. For example, tanker trucks comply with American Petroleum Institute (API) standard 1004, which dictates the unloader diameters—most are 4 in.—and the adapter design, which is a coupler that meets API specifications.

In other cases, it’s not so simple. Of course, everyone who has to unload bulk liquids would like to maximize the flow rate, which means using the largest-diameter pipes, the fewest bends, and the smallest number of fittings and adapters possible. However, most applications lack standardization, so it’s impossible to know if a port diameter will match the loading arm diameter, and adapters sometimes are required. While they can restrict the flow rate, adapters provide enough flexibility to handle any unloading situation.

Many swivel-joint styles also are available to suit the many bulk fluid delivery applications, such as joints fitted out with food-grade seals and grease, or dual seals for caustic chemicals.

“The loading arm also can have a built-in port with a sensor so the contents don’t come into contact with the atmosphere,” Williamson said. Some chemicals are so reactive that they become flammable, or even explosive, when exposed to air.

Standard Features and Options. The versatility doesn’t end with adapters. While each loading arm must have a couple of standard features, many options are available to provide maximum utility:

- A loading valve to start and stop the flow of the product

- Grounding or bonding to prevent a spark at the point of connection due to static electricity buildup

- Vapor recovery to capture fumes

- Vacuum breaker to free a stopped flow

- Steam jacket to keep the product at the proper temperature while loading

- Lockdown device

- Drop hose

Length Options. Bottom-loading can be a challenging application.

“To unload cargo through the bottom of a tanker truck, excellent positioning is necessary,” Williamson said. If it’s a matter of using the same drivers over and over, and drivers get a sense of the right spot for the truck, the unloading station can get by with a fixed-length arm. However, if the drivers aren’t regulars on that route, or the stop isn’t a frequent one, it’s much more difficult for the drivers to position the truck where it needs to be. A variable-reach loading arm, one with an additional length of tube plus two additional swivel joints, allows the loading arm much more positioning freedom.

Excel’s longest-length tubes run 14 ft., which is the limit of its fixed-length loading arms. It’s variable-length loading arms can run up to 26 ft.

No Pain, No Strain

Williamson estimates that a typical 4-in. loading arm weighs 300 to 500 lbs., so how does the depot operator swing a loading unit into position and retract it, off and on throughout the day, without strain?

To alleviate operator fatigue, Excel designs and manufactures its own spring cylinders—a spring inside of a tubular housing, of course—that supports the weight of the arm. It also provides pneumatically powered and hydraulically powered balancing systems.

It’s a matter of going beyond making loading arms that work and developing products that are as easy to use as possible. Reducing the effort associated with unloading 140 billion gallons of gasoline annually stands to save quite a few depot operators from repetitive stress injuries.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Team Industries names director of advanced technology and manufacturing

Orbital tube welding webinar to be held April 23

Chain hoist offers 60-ft. remote control range

Push-feeding saw station cuts nonferrous metals

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI