- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Zero to sixty in the blink of an eye

- By Eric Lundin

- November 20, 2003

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

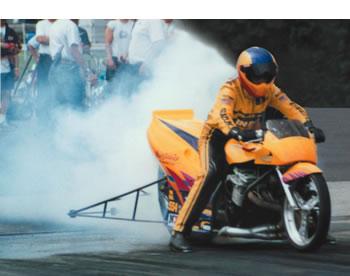

Bruce Van Sant heats the rear tire just before a time trial at The Big Race at Brainerd International Raceway, Brainerd, Minn.

It would be no exaggeration to say that Bruce Van Sant grew up around motorcycles. The youngest of three Van Sant brothers, he rode motorcycles all over the family farm as a child. He was exposed to racing at a young age, too.

"Our oldest brother Jeff used to race a '57 Chevy," recalled Craig Van Sant, Bruce's older brother. "He got me involved with racing by making me a partner on his racing team." Years later when Craig was driving hotrods and racing, he pulled the youngest brother, Bruce, into the sport.

"Actually, they told me not to worry about racing," said Bruce, clarifying the story. "They said by the time I'd be old enough to drive, gasoline engines would be gone and everything on the streets would be electric." He spent some time wondering how he'd go about getting racing-caliber performance from electric motors and batteries, but eventually gave up and hung his hopes on using traditional fuel. During his high-school years, Bruce turned hope into experience by working as a crew member for Rusty Kramer, a local gearhead and racing buff with a talent for metalworking.

"You learn a lot about the metalworking trade when you're involved with racing," Bruce said. And he learned a lot about everything that makes motorcycles fast: building modified engines, wiring and troubleshooting electrical systems, and fabricating lightweight tubular frames and wheelie bars.

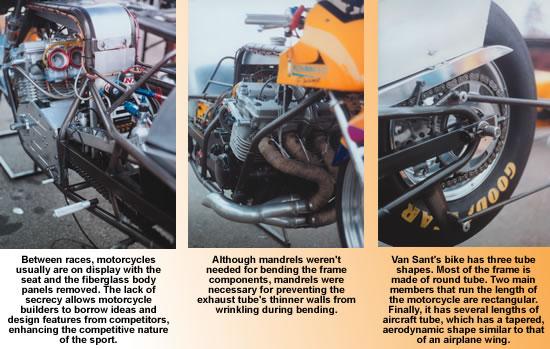

Building a Bike from Scratch

The world of motorcycle racing isn't swarming with university-educated engineers, people with Ph.D.s in mathematics, or eggheads carrying slide rules. It's full of people like Rusty and Bruce–regular guys who use and share information, common sense, and experience. They even share racing tips with their competitors. While a typical racer probably wouldn't divulge everything he knows, he wouldn't mind giving a few pointers to a newcomer or talking shop with a seasoned peer. This informal information exchange keeps the sport competitive. Likewise, design ideas are among the worst-kept secrets in the sport. Between races, motorcycles are on display for everyone–fan and competitor alike–to see.

Bruce saw many bike designs during his years of crewing and racing. He took many notes and snapped dozens of photographs over the years. When he and Rusty set out to build Bruce's latest bike, they incorporated many of the best design features they had seen and came up with a couple of new ones, too.

Following the Rules. The rules that govern motorcycle drag racing in the U.S. are set by AMA/Prostar. The organization's rule book allows a great deal of design freedom for the frame. Section 2.4.2, titled Frame Construction, stipulates heli-arc welding and suggests 4130 chrome-moly steel. The minimum tube diameter is 1 inch and the minimum wall thickness is 0.058 in. It also specifies that if the main top structure of the frame is made from a single tube, it must be 2 in. in diameter. That's it, except for a few details on minimum seat height, minimum ground clearance, and the minimum and maximum wheelbase.

Although chrome-moly is stronger than steel, which allows racers to use less material and thereby save weight, it does have one main disadvantage: It work-hardens and becomes more and more brittle as it absorbs the shocks and impacts during the race. That notwithstanding, it is the accepted material of choice for drag racing, mainly because the rate of work-hardening is slow. "During an entire weekend of racing, the bike might race for a total of 48 seconds," Bruce said. Despite the cold working that occurs, a well-built frame can last for more than 10 years.

Preparation is Key. Like any fabrication project, building a motorcycle frame requires a lot of cutting, bending, fixturing, and welding. These aren't the only steps, though. Fixturing and welding require quite a bit of setup and prep work, too.

"We made the frame from scratch," said Bruce, "by using an I-beam as a main fixture." After centering and leveling the engine on the I-beam, they clamped it into place. They then centered, leveled, and clamped the rear axle and steering neck into their positions. With these three main components fixed, they set about designing and building custom fixtures to hold every length of tube for the frame.

In addition to the fabricated tube used for the frame, Van Sant's motorcycle also includes several over-the-counter items made from tube. The handle bars, some of the steering components, the front forks, and even the gas spring that works as a steering damper (lower left) are all tubular components.

"Building the fixtures was an overwhelming task," Bruce said, "because every component had to be located somewhere in 3-D space." Although he and Rusty had several reference points to work from, fabricating custom fixtures was a time-consuming and tedious process.

|

"Some people look at the finished motorcycle and think that it might have taken a few weekends to build," Rusty said. "It took a few weekends just to plan how to build the fixtures!"

Successful heli-arc welding, or gas-tungsten arc welding (GTAW), also requires significant preparation. "Heli-arc welding requires nearly the same level of cleanliness as surgery," Rusty said. The process goes awry when any of the components–workpiece, filler rod, or electrode–is contaminated or dirty. "Everything must be very clean. This is tricky because many tubes have corrosion prevention coatings that must be removed. Then, everything must be wiped down with acetone immediately before welding."

Even though it requires such a high degree of cleanness, GTAW is well suited to this application. "It's a precise welding process that can be used on materials as thin as 0.035-in.-thick steel or 0.040-in.-thick aluminum," Rusty said.

Part fit-up is just as crucial as cleanness. GTAW is somewhat unforgiving in that gaps between parts must be 1/16 in. or less, according to Rusty. Successful GTAW requires a great deal of experience, too. "There's a fine line between too little and too much heat," Rusty said. "For thicker materials, such as 0.095 or .083 wall, there's a big window of acceptable heat. With thinner materials, such as the 0.058 used in the motorcycle frame, the window is much smaller. Still, it's a good process for this application. Usually you can tell a good weld with a visual inspection." AMA/Prostar rules prohibit grinding or painting welds for this reason.

More Speed on the Track and in the Pit. Because the AMA/Prostar rules aren't very restrictive, motorcycle designers have a lot of freedom to incorporate new ideas. Bruce conceptualized a chassis that would make maintenance a breeze, allowing easy access to areas where adjustments and repairs are most frequent. He also wanted to make it easy to remove and replace the entire engine, which is required about every eight to ten runs. He and Rusty also used a few tricks to reduce the frame's weight. All of these innovations were more than weclomed by Craig and the pit team's third member, longtime family friend Alan Geetings.

Although most racing motorcycle fuel tanks are fabricated from pipe, Rusty and Bruce put together a bolt-on, quick-disconnect tank fabricated from sheet aluminum. The tank is easy to remove, which gives the crew fast and easy access to the engine. They hand-fabricated each motor mount from short sections of tubing and bushings. After disconnecting the engine from the motor mounts, the crew can swing the motor mounts out of the way, which speeds up removal and installation of the engine. They even went so far as to profile some of the bolts that hold the bike together, removing some material from the bolt heads and drilling out the centers of the bolts. This follows a racers' maxim: It's easier to find 16 places to remove an ounce than a single place to remove a pound.

They focused just as much attention on the wheelie bar as they did on the main frame. Having a lightweight, sturdy wheelie bar is crucial for stability during a race. A wheelie bar can vibrate during a race, and a massive, sloppy wheelie bar would transfer some of the vibration to the motorcycle frame, making the motorcycle more difficult to handle.

"To save weight, some motorcycle designers are using aluminum wheelie bars," Rusty said. Rusty had doubts about using aluminum. Concerned that welding could make aluminum too brittle to stand up to the abuse that wheelie bars take, they decided to use the conventional chrome-moly steel. But they found a way to reduce its weight nonetheless.

"Most wheelie bars have the same diameter tube in the top and bottom tubes," Bruce said. "I don't think it's necessary to have them the same size."

Although he looks calm, cool, and collected, Bruce Van Sant usually has little time to gather his thoughts before a race. The motorcycle requires frequent teardowns, and often Bruce transitions from mechanic to driver in mere minutes.

"The bottom tube is under tension, so it doesn't need to be as strong as the top tube," Rusty concurs. However, the top tube is under compression with some side-loading force, so it needs a higher yield point and therefore is made from a larger-diameter tube.

They didn't stop there. "Wheelie bars have threaded hardware so they can be adjusted, but most designs put all the stress on the threads," Bruce said. Bruce came up with an original design that keeps the stress off the threads. To top it off, he attached it to the motorcycle's frame with quick-disconnect fasteners.

Craig walks across the track near the starting line, looking for the best possible path down the track. After finding a good spot, he points to it and Bruce brings the motorcycle forward to the white line, lining it up with the spot Craig picked out. Alan approaches the back of the motorcycle and, if the bike isn't perfectly perpendicular to the starting line, picks up the back end and moves it over until the motorcycle is lined up.

With the motorcycle in position, only a few seconds remain. Bruce purges the nitrous oxide from the system so that, when it's show time, the engine will get a boost of fresh nitrous straight from the tank rather than the nitrous that has been bubbling through the fuel system.

Alan crouches next to the motorcycle and flips the remaining switch on the onboard computer system to start gathering data. The system will record dozens of parameters for later downloading and analysis.

When the other racer appears to be ready, Alan taps Bruce on the leg to let him know that everything is in place, lined up, and ready to go. He steps away from the motorcycle, and Bruce is on his own.

Move It or Lose It!

After racing at local tracks for several years, Bruce stepped into the professional circuit when he purchased a nitrous oxide system. It was a much bigger step than he anticipated.

"I told the other guys I was just adding a little nitrous, and they laughed," he said. Bruce didn't know this at the time, but there is no such thing as "a little nitrous." It gave his motorcycle an instantaneous 60-horsepower kick in the seat of the pants.

"I was hooked," he said.

The engine, a Suzuki GS block topped with a Suzuki GSXR-1100 cylinder head, develops about 225 horsepower. The current nitrous system adds another 250 horsepower.

"Racing is a matter of managing problems," Bruce said. One of the main problems is figuring out how and when to effectively transfer 475 horsepower from the tire to the track. Too much, too soon is just as bad as too little, too late.

"We usually program the fuel system to start out pumping about 25 to 30 percent of the engine's total fuel capacity," Craig said. "Over the course of the race, the fuel system ramps up to peak at 100 percent of the engine's capacity. If we started out at 100 percent, the motorcycle wouldn't even move. The back tire would immediately break loose from the asphalt and just spin and spin."

Another problem–or set of problems–crops up at every single race. Weather conditions, including air temperature, track temperature, and humidity, affect the motorcycle in different ways and require a variety of measures to counteract their effects. The air temperature and humidity affect the fuel mixture, which affects the engine's performance; the track temperature affects the rear tire's traction, which also is influenced by the engine's performance. Small adjustments in one area sometimes force counteradjustments in other areas. And it's largely based on experience; the team does not have the luxury of trying out new combinations of settings on public roadways.

"People sometimes ask if I take it out on the streets to test drive it," Bruce said. It's not much like a street motorcycle. It doesn't steer well, it's hard to handle, and it runs poorly when its burning straight gasoline, even 118-octane racing fuel. In short, it's a racing platform–a finicky, temperamental beast best suited to a very short, straight track, not a road.

But for all of the difficulties the sport poses, the pool of experience among the Van Sants, Kramer, and Geetings has served the team well. The bike goes from 0 to 60 miles per hour in 1 second, 0 to 100 MPH in 2.10 seconds, completes 1/8 mile in 4.41 seconds with a top speed of 170 MPH, and finishes 1/4 mile in 6.91 seconds with a top speed of 194 MPH.

Bruce presses the rev limiter button, then opens the throttle completely. When the lights flash green, Bruce releases the rev limiter. The months of planning, weeks of preparation, hours of fine-tuning, and last-minute checks are behind him.

The engine speed instantly jumps and the motorcycle roars across the starting line. To prevent the back tire from going into an uncontrolled burnout, the fuel system starts out pumping much less fuel than the engine can handle. During the next four seconds or so, the fuel system will respond to commands from the onboard computer and dump more and more fuel and nitrous oxide into the cylinders until it peaks at 100 percent of the engine's capacity. Meanwhile, Bruce will run through all five gears. Shortly after that, the front wheel will touch down with a puff of smoke and the bike will streak across the finish line.

Races aren't always trouble-free; problems often crop up during a race. A strong sidewind, a stuck shifter, a faulty spark plug–any of these can make the difference between winning and losing. Racing is a matter of managing problems, and the most critical ones are those that crop up during the 7 seconds of the race.

By the time he crosses the finish line, Bruce will know if he has managed them well.

AMA/Prostar, P.O. Box 18039, Huntsville, AL 35804, 256- 852-1101, fax 256- 859-3443, www.amaprostar.com.

Van Sant Enterprises Inc., 80 Truman Road, Pella, IA 50219, 641-628-3206, fax 641-628-2614, www.vansantent.com.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Team Industries names director of advanced technology and manufacturing

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI