Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Watch and adjust: How manufacturing companies of today can learn from the Digital Equipment Corp. collapse

- By Lincoln Brunner

- May 30, 2023

A quarter century is a long time.” So said Mattie Ross at the end of 2010’s “True Grit” as she searched for Rooster Cogburn, the U.S. marshal who’d saved her life 25 years before, right after she avenged the death of her father. Alas, Cogburn himself had died just days earlier.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of another death—that of the once-mighty Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC), which ceased to be a stand-alone company in 1998 when it was purchased by Compaq (which itself would merge with Hewlett-Packard just a few years later).

What led to DEC’s demise has been studied, debated, and whispered as a warning ever since. Was it hubris? Perhaps. Stupidity? Not a chance— DEC’s leadership was rightly considered among the brightest the tech industry has seen. So, what exactly steered DEC into an early grave, and what can manufacturers today learn from the giant’s collapse?

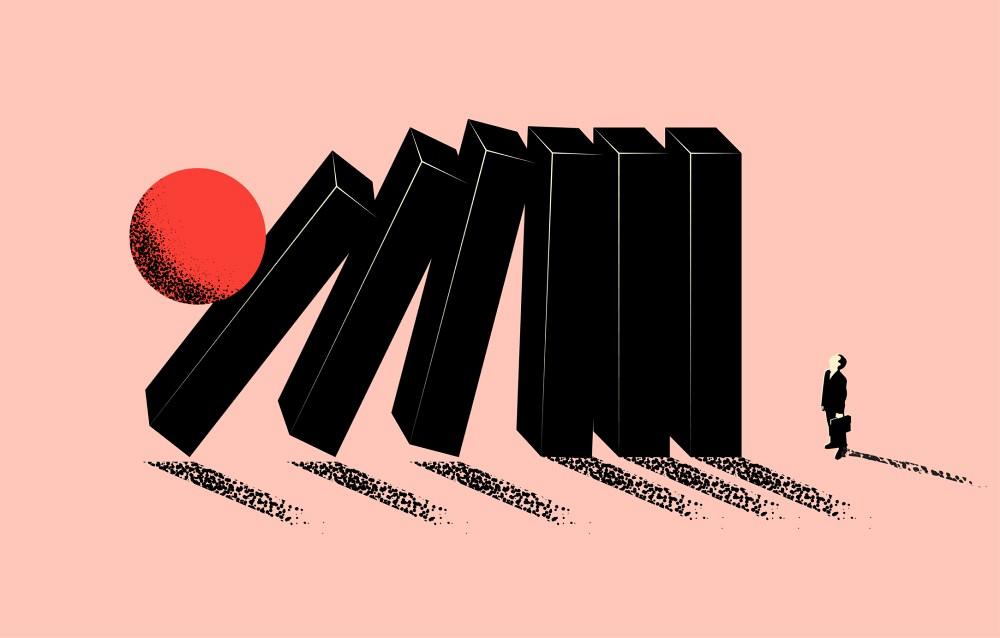

One thing seems clear: Continued success requires you to scout the landscape and adjust.

The irony was that innovation was second nature to DEC. For its first 20 years, DEC championed the new—and made billions of dollars from it. In fact, what had propelled the company to the top of the tech world by the late 1970s was the eminent usability and popularity of its revolutionary PDP-11 and VAX minicomputers. (Even mighty IBM only made plays at competing in that space.) Those wildly successful computers made the components that launched DEC in 1957 look like Stone Age hand tools by comparison.

But then—then something happened that turned the tide forever. In “True Grit”, it was Mattie finally avenging her father’s death. In early ‘80s computing, it was DEC getting smacked by a proverbial bus for which its technology (again, ironically) had paved the way—the microcomputer.

How? As in all races, it came down to timing. IBM, sensing a market opportunity, quickly downshifted and turned—launching the IBM personal computer in August 1981 after nimbly creating the secret company division that designed it. Instead of doing the same, DEC decided to cruise in fifth gear with its minicomputers—and ran itself off the track. It wouldn’t introduce its Rainbow 100 PC until the following year; by that time, IBM had become synonymous with the PC and sewn up the market.

DEC would remain profitable for many years after, but it had missed a critical turn in a consumer electronics race that fundamentally changed the way the world worked.

The thing is, a company with DEC’s resources, brainpower, and market dominance should have seen the revolution coming and been ready. After all, everyone knew Moore’s Law—the number of transistors on a microchip doubled roughly every 18 months. That trend was making memory cheaper and cheaper, putting significant computing power nearly within consumer reach. By 1981, the world was ready for something new—but DEC somehow wasn’t ready to deliver.

Some blame the company’s failure to adjust on the rigidity of its business model; others blame the East Coast snobbery of those leaders who disregarded upstarts from the West Coast like Apple, Intel, and the rest.

“We know when leadership is at a point where they see success, they need to get up on the top of the mountain and look and be a visionary to see what’s coming next,” said Dr. Mary Hinesly, a professor of executive education at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business. “You can’t believe it’s just going to continue. The saddest thing for me was that they [DEC’s leaders] literally sat on their laurels in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. They just kept doing the same thing. And for me, that is a leadership failure.”

As Mattie remarked at the end of the film, “Time just gets away from us.” May it never get away from us so much, though, that we forget to keep educating ourselves and peering around the corner to see what might be coming next. It may just be the next turn that proves to be the most important.

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

Lincoln Brunner

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8243

Lincoln Brunner is editor of The Tube & Pipe Journal. This is his second stint at TPJ, where he served as an editor for two years before helping launch thefabricator.com as FMA's first web content manager. After that very rewarding experience, he worked for 17 years as an international journalist and communications director in the nonprofit sector. He is a published author and has written extensively about all facets of the metal fabrication industry.

About the Publication

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Team Industries names director of advanced technology and manufacturing

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI