- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Inclusions caught with PAUT

Phased-array ultrasonic unit detects tiniest flaws

- By Eric Lundin

- February 17, 2014

- Article

- Testing and Measuring

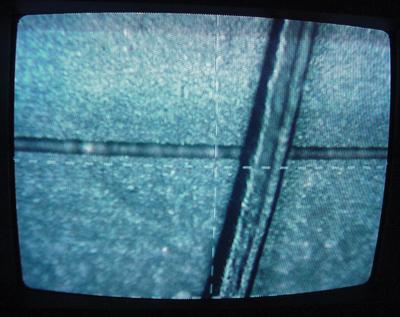

Phased-array ultrasonic testing equipment is calibrated using a micronotch that measures 0.001 in. wide, which runs horizontally in this image. A human hair, which has an average diameter of 0.003 in., is shown for scale.

Tube and pipe producers are familiar with ultrasonic testing (UT) which, as the name implies, uses high-frequency sound waves to find discontinuities in tube and pipe. It is often combined with eddy current (EC) testing, which sends a small amount of electrical current through the tube or pipe. In both cases, a smooth, freely flowing signal indicates good material; a disruption in the signal’s characteristics is an indicator of a discontinuity, such as a bad weld. They work well together because EC finds short, abrupt flaws, whereas UT finds long flaws that start small and grow. Also, UT penetrates metals well, making up for EC’s inability to get much below the surface.

While conventional UT is effective for testing raw materials with simple shapes—round tubing, rectangular billet, and rectangular plate—complex shapes such as castings and assemblies need something more. Speaking at the EDTR Roundtable 2013 in Silverton, Ore., Michael Powell, president and co-owner of Westpro Lab, Salem, Ore., explained that the phased array ultrasonic test (PAUT) is that something more. Much more. PAUT uses a large number of test signals in several phases to produce a much more complete picture of a component’s internal structure than standard UT.

“Our PAUT equipment can use more than 200 discrete elements and produces up to 256 individual beams,” Powell said. “The beams can be steered back and forth without moving the transducer.” It can also be used on long, large-diameter tubes, providing the test resolution far beyond conventional immersion and contact inspection. A typical test specimen is a forged titanium flange joined to an extruded titanium tube by a method known as friction inertia welding (also known as inertia welding).

“Conventional UT has a lot of difficulties detecting small indications in titanium castings due to the large grain size that titanium produces,” Powell said. “When we started implementing PAUT inspection, we were able to find substantially smaller inclusions. We also found that it improved our ability to detect indications throughout the casting, including flaws in hard-to-inspect areas like heat-affected zones. With PAUT we were also able to see a variety of grain sizes,” he said. A large, complex casting can produce many grain zones due to thickness changes throughout the casting, according to Powell.

PAUT is similar to UT in that the technician needs to use an artificial flaw to calibrate the equipment. A chief

difference is that PAUT gives the option of sweeping the UT beam back and forth electronically, which provides more testing versatility than a standard system, which has a single beam.

“PAUT is beneficial in detecting microscopic gas pockets trapped in cast titanium, with indications often measured down to 0.007 in. dia.,” Powell said. A key strength is its ability to detect an indication from multiple angles. “If we find an indication in one dimension only, and it does not track on several focal laws, there’s a good possibility it is just a grain boundary,” Powell said.

The ultimate test of Westpro’s PAUT system was inspecting large titanium castings.

“PAUT detected 40 indications in one section of the casting,” Powell said. “Later, when it was cut up, all 40 inclusions were validated.”

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 05/07/2024

- Running Time:

- 67:38

Patrick Brunken, VP of Addison Machine Engineering, joins The Fabricator Podcast to talk about the tube and pipe...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

Making the move from hard automation to robotic welding

Miscellaneous metals fabricator increases productivity and opportunity with plasma cutting

- Industry Events

Laser Welding Certificate Course

- May 7 - August 6, 2024

- Farmington Hills, IL

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,