Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Why fabricators should get to know cobotic bending

The new alternative for press brake automation, without the expense of fixed robotics

- By Dan Davis

- April 6, 2024

- Article

- Automation and Robotics

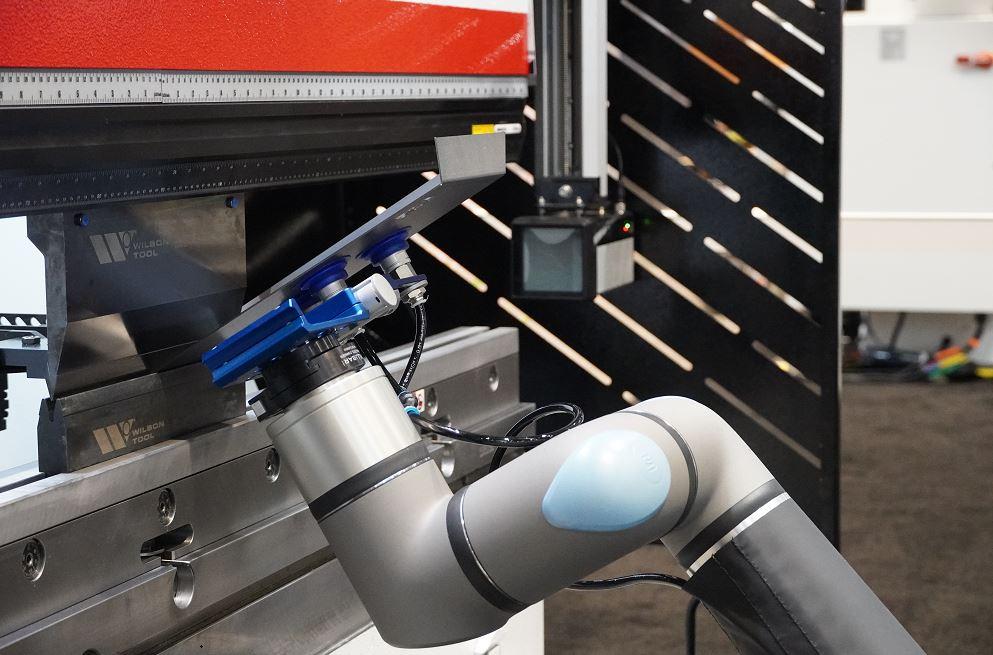

Using a cobot for a bending application allows a metal fabricator to test the idea of automated bending without the need for investing in a cell with a robot and the associated guarding required for such automation. Images: Cincinnati Incorporated

Only a few years ago, collaborative robots, or cobots, were rolled out to demonstrate their viability in welding applications. An operator—who didn’t need to be a welder—could take the cobot, teach it by moving it along the prospective weld path, and start the welding process.

Today, shops typically fall into one of two categories: They either have a welding cobot, or they are looking into possibly bringing one into the welding department. The cobot’s flexibility, ease of programming, and relatively inexpensive cost when compared to fixed robotic welding cells are a huge attraction.

The attraction is strong enough that metal fabricators are looking to see where else they might be able to use these automation tools. It should come as no surprise that most of the attention now is focused on the bending department.

Ryan Lemmel, business unit leader—aftersales, Cincinnati Incorporated, witnessed the increased interest in cobotic bending at FABTECH in 2023. His company introduced a low-code programming cobot attached to a mobile workstation that can be wheeled up to a stand-alone Cincinnati press brake.

“The feedback was great at the show, and the interest has been strong,” Lemmel said. “I think it’s the right time for something like this.”

The Fabricator spoke with Lemmel to find out what metal fabricators should be aware of as they investigate using a cobot for bending.

What type of bending application is best for using a cobot at a press brake?

The part size and shape really govern whether a cobot might be able to do the job or not, according to Lemmel.

For instance, the Cincinnati cobot is a Universal Robots UR20 model, which has a payload of 20 kg (just over 44 lbs.) and a reach of 1,750 mm (almost 69 in.). With that in mind, Lemmel said the best parts for the cobot are those that are 35 lbs. or less.

Additionally, the part needs to have a flange long enough to allow it to be picked up and maneuvered to complete the bending sequence. Parts that need multiple regripping stations and/or changing end effectors are indicators that the job might not be the best for a simple cobot setup.

Suction cups on the end effector provide secure handling of metal parts while simultaneously minimizing the risk of marking or damaging the parts.

“Whether it’s a suction cup, magnet, or a gripper that you use to pick up the part, you will want to use the same end effector for most individual bending jobs,” Lemmel said.

Should a part have a limited number of bends when a cobot is involved?

Lemmel said that he has seen jobs with as many as 10 bends processed with the cobot. The part geometry really determines if multiple bends might be possible during one sequence. For example, a job with intersecting flanges can be challenging, but multibend jobs are possible, sometimes with a little creative thinking.

“For a lot of parts, we’re actually able to use the press brake as a regripping opportunity because we regrip at the bottom of the stroke,” Lemmel said. That keeps the bending process going without the need for moving the part to a regripping table or requiring a different end effector.

What kind of repeatability can a metal fabricator expect from a cobot and a press brake?

The UR20 cobot can deliver a tolerance of 0.05 mm (almost 0.002 in.), and the Cincinnati press brakes all maintain ram repeatability within 0.0004 in., according to Lemmel.

But what really helps with repeatability are the force sensors within the cobot. In traditional automation, a proximity switch (or some other type) is installed within the backgauge to ensure that the part is positioned properly against the backgauge. With the cobot, the end effector pushes the part forward along the axis of movement; it’s only when the part engages with the backgauge and the right level of resistance is noted that the ram is engaged.

Does a metal fabricator need to be concerned about safety when using a cobot for a job?

“That’s always an important consideration because at the end of the day, the shop owner is responsible for providing a safe workplace,” Lemmel said.

A metal fabricator has to recognize that any such automated bending operation is worthy of a safety audit before anything is implemented. The cobot is engineered to work closely with humans, with rounded joint areas and sensors that shut it down if contact occurs. However, this type of automated setup also includes variables, such as the size of the workpiece being handled. At the very least, it’s important to keep people away from the bending area as the cobot handles workpieces.

Placing the cobot in front of the press brake is the first step in establishing a cobotic bending cell. The tables for blank pick-up and part drop-off have to be arranged nearby.

Lemmel said that Cincinnati includes optical scanners as part of its cobotic bending package. The scanners ensure that humans aren’t present within the press brake area as forming is taking place.

If someone enters the periphery of the area being scanned, the cobot slows down considerably from its regular operating speed. If the person more deeply penetrates the operating zone, the cobot stops. Lemmel said that further safety steps, such as integrating an e-stop for the brake, can be included as well.

How does an operator program a cobot?

Lemmel said that programmers with press brake experience can quickly learn how to program the cobot for a bending operation. A mechanical engineer with experience in manipulating a 3D model is not necessary.

Cincinnati provides a basic program on which all the cobotic bending jobs can be based. Because a majority of the program has a similar flow, this can be a starting point for someone new to cobot programming.

Because of this, the program starts with the cobot and the gripper taking a part from the table, presenting it to a double-blank detector to confirm that only a single piece has been picked up from the inbound stack, and presenting it to the press brake. This is the point where the job can be tailored. Lemmel called it establishing the cobot’s waypoints.

An operator can move that cobot in free drive, from one point to the other, and record it. That creates the waypoint. This step is repeated, even through multiple bends, until the last waypoint is recorded, placing the formed part on the outbound side of the table. These waypoints also can be tweaked later and copied, if necessary.

The cobot’s software is sophisticated enough that it even records the force being applied during the presentation of the part to the backgauge. Again, this particular sequence can be copied and reused in programming a multibend job.

“How someone programs a cobot will be based on preference,” Lemmel said. “In the beginning, operators probably will touch up an existing program and create a new one from that. But as they get more comfortable, they might want to start from scratch.”

With the use of an add-on software program, creating a bending program for the cobot is as easy as putting the cobot in free drive and having the software record the operator moving the cobot through the entire bending process. The software records every movement and the speed in which the cobot is manipulated.

Lemmel said that metal fabricators are typically told that it should take a programmer about 15 to 30 minutes to create a cobotic bending program. Obviously, a lot of variables exist, but the cobot’s ease of programming helps to speed up the process, especially when compared to programming industrial robots. After about three days of cobot training, a programmer should be proficient enough to create new jobs quickly.

Does an experienced press brake operator make for a better programmer of cobotic bending jobs?

“I absolutely think so,” Lemmel said. “They know what parts make the most sense for this type of automation. They know all parts of the bending process, such as the correct way to gauge parts using one or two fingers, for example. They know the order that the bends should take place. They know all of that stuff, and those are the keys that are important to making a good cobot program.”

Any other words of wisdom for metal fabricators looking to possibly add a cobot to the bending department?

Lemmel said that the addition of a cobot, particularly if operators are involved in the integration process, can help to raise the morale of a company. They keep hearing about how automation is inevitable in the modern metal fabricating company, but if they are involved, they get to see that automation can change the dynamic of how parts are formed, not necessarily that the cobot can replace jobs.

Additionally, finding those parties that want to be a part of proving out the automation will increase the odds of a successful implementation.

“You have to have that person who is going to be a champion for this, someone who is going to own the process and move it forward,” Lemmel said.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI