Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A better way to tackle that complicated bending job

In many instances, customized press brake tooling can make life a lot easier for a machine operator

- By Dan Davis

- May 28, 2021

- Article

- Bending and Forming

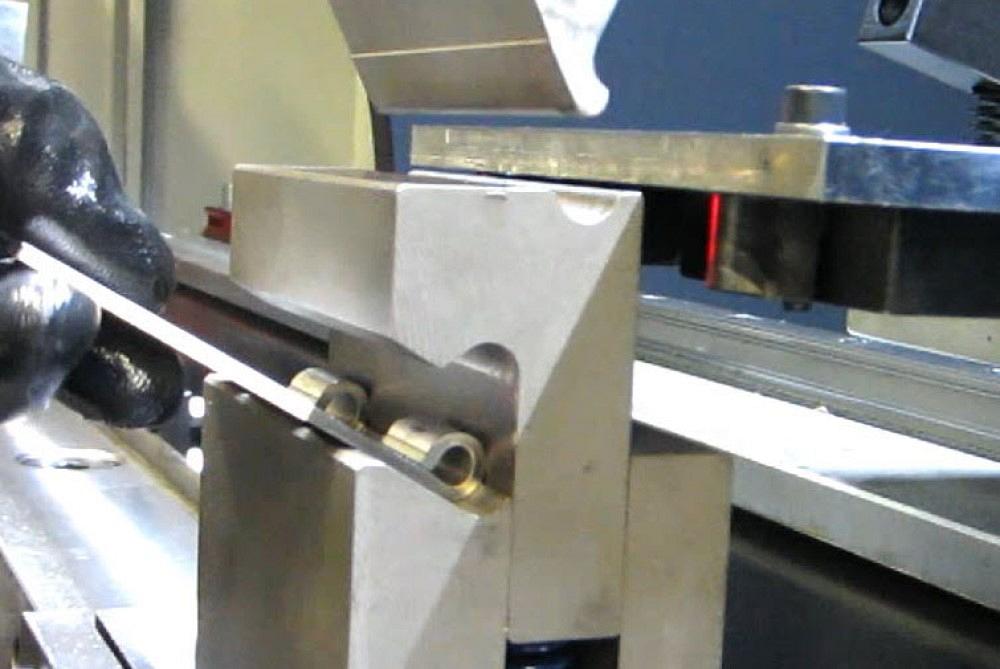

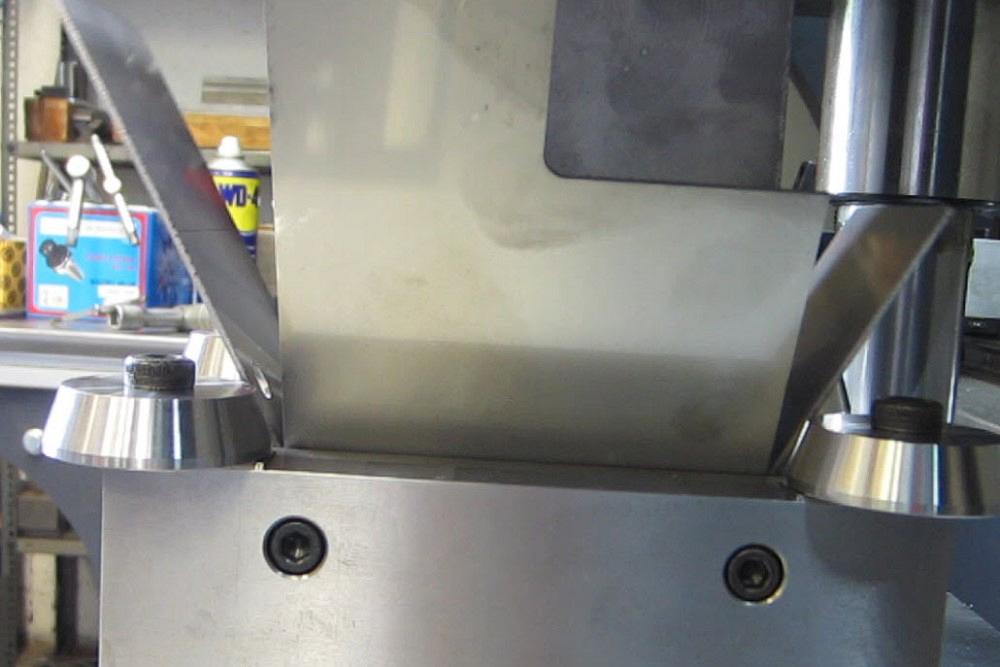

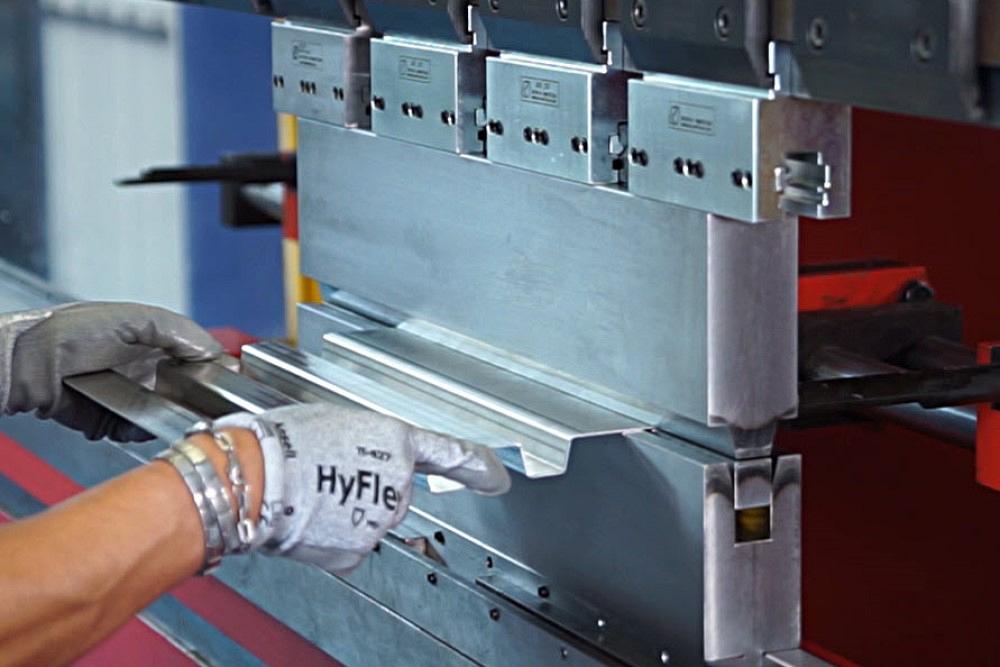

Need a large omega shape? Sometimes the most efficient way to create a form on a press brake is to have tooling that creates that form in the most expedient way possible. Images: Rolleri USA

“I’ve seen a guy with a Pacific press brake from the 1950s, and it was something to see. Now this is a thing that goes up and hammers down. It’s an endless cycle. There are no hydraulics or anything like that. So this thing was going.

“The press brake operator had found a way to stop it [before the ram engaged the material]. Also, there were no backgauges. And he kept talking about the ‘light.’ I was confused. What was the light? I said, ‘Can you show me?’

“He walked me over to the press brake, and he had some kind of light on the inside part of the upper beam. When the beam came down, it would stop at that exact point, just about 1 mm before the punch was about to touch the sheet. The shadow of the light would then tell him where to put the workpiece on that punch—and it was always the same punch. So, while you don’t have a backgauge on the press brake, you have a reference point. He knew where the bend was going to be. That’s how he could form a box and all the legs would have the same length.”

Julio Alcacer, international sales manager, Rolleri USA, shared that story in the midst of a discussion about experienced press brake operators retiring and leaving metal fabrication shops and taking years of institutional bending knowledge with them. The people that could hear a general description of a part, plan out the flat, draw it on a sheet, and step in front of the press brake to make it happen are few and far between nowadays. The industry recognizes that even the most advanced control systems can’t begin to capture all the institutional knowledge in the heads of these press brake veterans.

That generational transition in the bending department leads to another discussion of just what can be done to help metal fabricating companies dealing with more inexperienced press brake operators. Are the managers and owners of these shops putting their employees in the best position to form parts efficiently?

Alcacer estimated that the press brake wizard working on that giant mechanical brake likely was producing about 10 parts an hour on the machine—a truly remarkable accomplishment given the situation. But if that operator had a customized tool to do the job, how many more parts could have been knocked out? A guess of 100 parts per hour is pretty reasonable.

That’s the power of a custom press brake tool, according to Alcacer. It can make an inexperienced press brake operator more productive from the start and elevate an experienced bending technician’s output even more.

What often stands in the way of this type of investment, however, is a lack of recognition by the front office because they simply don’t have experience of being in front of a press brake. They know that orders for parts are received and that parts ultimately leave the shipping dock for delivery to the customer. They don’t really know what happens in between.

Alcacer referenced a simple hat form as an example. (Think of the form as a trough with a flat base and two elevated sides.) To create this shape without any special tooling, the press brake operator has to flip the sheet three times and correctly position the workpiece against a backgauge four times. Of course, that sounds easy enough if you don’t have to do it yourself—and do it repeatedly over a shift.

Now this form can be bent on a press brake because the base of the hat is longer than the side legs. If the base is shorter, problems will come up. In this scenario the only way to fabricate the part efficiently and within tolerance is a custom tool—either a hat tool with an extractor to get the part out of the die once it has been formed or a cam die where mechanical actioned cams bring the side legs up to form the part.

Instead of flipping over a part repeatedly to make this hat form, custom brake tooling can make the form in one hit.

To bridge the gap between what is unknown and what is possible with customized press brake tooling, Alcacer shared some of the more frequent requests his company gets from metal fabricating companies and how special tooling helps to solve their bending challenges.

The Z Bend

The Z bend or a joggle often is the most common request from customers, Alcacer said. It’s easy enough to understand. In a typical forming process, the workpiece is bent with a standard punch and die and then turned over to bend the other side. It’s a slow process, but it does the job. The customized tool is going to make that form in one hit. It also helps when the jump, where the bend is made, is so short that a normal two-stroke process cannot be done.

The catch is that the jump has to be longer than the material thickness. When forming occurs, the material has to go somewhere. If the bend length is shorter than the material thickness, that material has nowhere to go.

Forming a Hinge

Attempting to form a curl at the edge of a workpiece is difficult. Unlike a punching machine that has a clamping mechanism to grasp the sheet metal, the sheet has to be placed in the right position in the die to ensure an accurate bend.

Customized tooling can take a lot of the guesswork out of this effort, according to Alcacer. In such a tool, the first hit partially forms the curl as the ram forces the sheet into the curved die opening. The operator repositions the workpiece for the second hit, which further forms the rollover. The operator then moves it to another station, which many times can be incorporated in the front of the same tool in which the initial hits were made, where the ram descends into the die and slowly forces the curl to conform to the punch cavity, forcing the curl end into the sheet.

For this hinge form to be created, the internal diameter of the curl needs to be at least 3.5 times the material thickness. (Working with a soft material such as aluminum can provide some wiggle room with this rule.) Any diameter less than that will result in sheet metal that will wrinkle or even break, Alcacer said.

Putting a Short Flange on a Long Workpiece

Large parts can put undue strain on a press brake operator. They are awkward and an ergonomic pain to deal with.

Long parts that require a short flange are particularly challenging. The press brake operator places the long workpiece into position, and the punch comes down to drive the sheet into the die opening, causing the rest of the sheet to fly up into the operator’s face. Even if the overall workpiece weight might not be that much, the operator still might need assistance to handle the sheet as it is moving during the bend.

Customized tooling can help in this situation as well. Alcacer said that a rotary die keeps the long portion of the sheet from rising as the short flange is formed. He described how a 3-ft. workpiece would react as a 2-in. bend is made on its end: “What happens is that the punch drives the sheet into a die, shaped like a Pac-Man, and the die rotates to form the 90-degree form on the sheet’s end. The other 3 ft. stays where it is as the other side goes up. It’s like the process that is usually done on a panel bender.”

When a rotary die is used, the maximum flange depth is governed by the space available in the tool cavity. Alcacer said this type of tool is very helpful for press brakes with no front-sheet followers and thin-gauge parts with long legs.

Forming a Box in One Hit

Boxes are a pretty common form that metal fabricators are asked to create. They also require multiple bends and can be challenging for someone new to a press brake.

Alcacer recalled a tool his company made for a Mexican company that wanted a higher rate of production for forming boxes. Customized tooling, about 3 ft. long by 3 in. wide, was made to form the rectangle shape that had two extremely long legs and two shorter sides of a few inches. As the upper beam drove the upper tooling into the lower die, the lower tooling formed the long legs with little issue. To form the shorter legs, however, Alcacer said the lower die had cams that pushed the shorter legs out to a 90-degree form.

But the real problem was taking the formed box off of the upper tool when the ram retracted to its resting position. It was not going to slide off without a bit of help.

“We came up with a solution that we call ‘moving horns,’” Alcacer said. “So when we say the upper tool is 3 ft. long, it’s basically 3 ft. minus 1 in. on each side. The horns, which have springs, occupy those two 1-in. spaces. When the tool goes down, those two horns move to the side and fill out the 1-in. spaces. When the pressure is taken off of the upper tool, those two horns move back in. That provides the space to put your fingers in and take the part out.”

Bending Some Rod

Alcacer said he has seen increasing interest in custom rod bending tooling because inexperienced operators tend to try to bend rods on a standard tool, causing great damage to them. More specifically, they are placing a rod on top of a die opening and driving a punch into the rod. That ultimately ruins the upper die.

“What people tend to forget is that force is being applied to a small area. If you reduce the area of contact between a rod and the upper tool to where it’s basically nothing, you are just increasing the pressure at that one point. You end up breaking the upper tool,” Alcacer said.

The customized tool is designed to eliminate tool damage during rod bending by increasing the surface area involved in the forming process. This distributes the force across that increased area.

Because rods are available in common diameters, such as ¼ in. and ½ in., exact forms in the upper and lower die are machined into the tooling. The press brake operator places the rod into the respective groove and initiates the ram, and the punch makes contact with the rod and forces it down into the grooved lower die.

Because the customized tool accommodates different rod diameters and the price is slightly less than other special tooling, Alcacer said the rod bending tooling has become very popular. He jokingly called it a “standard custom tool.”

Ensure the Tooling Pays for Itself

These examples of custom press brake tools all solved a specific production challenge for metal fabricating companies. The company leaders made the investment because they knew productivity and quality would improve.

Alcacer said that custom press brake tooling should not be purchased with the idea that eventual work could end up paying for the tooling. Customized tooling is not general-purpose tooling. For example, a customized hinge tool is made to work with a certain material thickness and to deliver a certain diameter hinge. That’s it. The customized hinge tool isn’t going to be flexible enough to work for a somewhat similar job. That creates a situation that the programmer and the press brake operator need to keep in mind.

Also, if a shop doesn’t have bending programming software that keeps track of its bending tools, customized tools can easily be forgotten about. If they are out of sight, they can be out of mind.

Alcacer said purchasing managers, parts programmers, and press brake operators need to be aware of what customized tooling can do for them and when it makes sense. It can make a significant impact, especially when a company is looking for a better way to form parts on the press brake.

“Once you are challenged, you have to put forth effort to find a better way. And when you put your effort into something, you start learning,” he said.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Trending Articles

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

How laser and TIG welding coexist in the modern job shop

Robotic welding sets up small-batch manufacturer for future growth

Ultra Tool and Manufacturing adds 2D laser system

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,