President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A tale from the pretreating and powder coating front lines

Pretreating and coating even a simple metal box isn’t so simple for some fab shops

- By Ted Schreyer

- May 21, 2020

- Article

- Finishing

Editor's note: This fictional tale is based on actual challenges that have occurred over the years. The names have been changed to protect the innocent.

I couldn’t help but have a smile on my face while driving to work that morning. All week I had wanted to work on the design for our new paint line, but daily interruptions kept getting in the way. Today would be a perfect day to stay in my office and focus on the plan since the main job in the plant was just powder coating a simple steel box with only one threaded hole to mask (see Figure 1).

When I entered my office the phone message light was already flashing. It was a call from Quinn, our shop foreman, saying he needed me to look at something right away. Quinn was a dependable, hard worker, but he sometimes lacked confidence and he probably just needed me to verify something he already knew. This should be quick.

As I approached the powder line, I could see a trail of oil on the floor leading from the warehouse right to the skid of parts next to Quinn. “Hey, boss, look at this mess. The customer really overdid it with the rust preventive oil. I realize they had some rusty parts last week, but this is ridiculous!”

The parts were scheduled to run on our line with the three-stage washer since this customer normally has fairly clean parts. We get good results with this washer as long as the parts aren’t too oily or greasy. Considering this excessive oil, we weren’t too confident.

The three-stage washer carries parts on an overhead conveyor through a cleaner/iron phosphate zone followed by two rinse zones. Sent through a single stage of cleaning and phosphating, the parts spend part of the time in the first stage getting clean before the phosphate coating develops.

To build phosphate, there also must be acidity in the bath, and acidic cleaners tend to be less effective than alkaline cleaners. With the amount of oil on these parts, we were afraid we wouldn’t get a good phosphate coat, or we may not get the oil completely removed using this washer.

“We’d better move the job to the five-stage line,” I told Quinn. He agreed and was already prepping his crew for that task.

The five-stage washer is similar to the three-stage one in that a conveyor carries the parts through the spray zones. The cleaning and phosphate are split in order to take on filthy parts. Stage one is an alkaline cleaner, which tends to clean most oils better than an acid. It’s followed by a rinse during the second stage. Stage three is an iron phosphate that’s acidic and builds a nice pretreatment coating to hold the paint and provide corrosion protection. It also does some additional cleaning at the acidic level. Stages four and five are two more rinses. With the parts staged to run on this line, I knew my worries were over, so I could get back to my office.

I just settled into my first cup of coffee and some quick emails when my phone rang. “Boss, can you take a look at this?” I always hated it when Quinn called me boss, but I couldn’t get him to quit so I gave up trying. “I’ll be right there,” I replied.

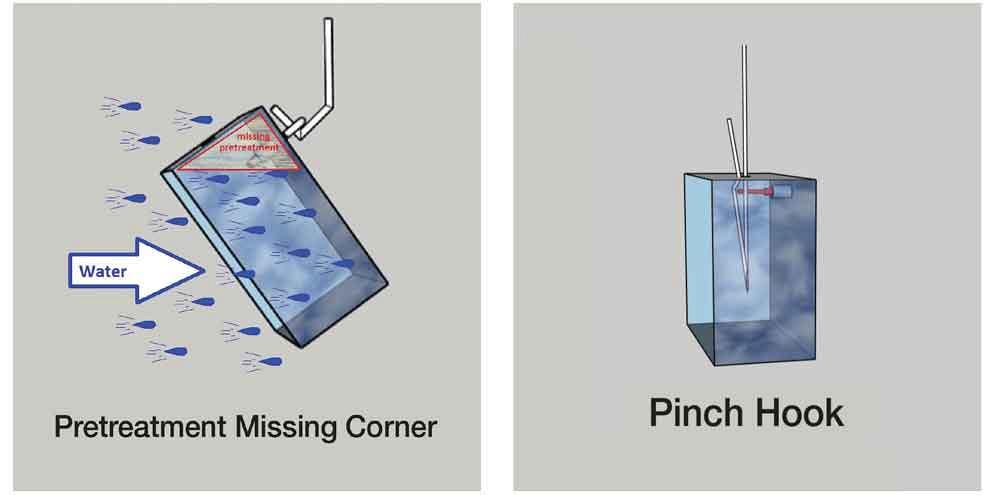

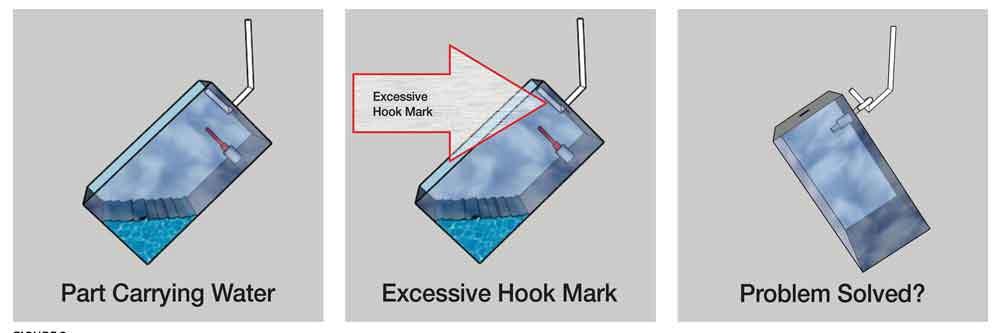

The first parts were just coming out of the oven, and Quinn was holding one and shaking his head. “I just don’t get it. Every part has got powder separation in the bottom corner—and look at this. Most parts have a huge hook mark in the top side.”

We walked back to where the parts exit the dryoff oven and saw that each part had a band of rust in the bottom corner. This rust caused the powder to separate when it melted. When we looked at wet parts coming out of the washer, we saw that each part carried a pool of water in the bottom. This is what dried and became rust. We also saw that the top side of the box had shifted in the washer and was resting firmly on the hook (see Figure 2).

To correct this, Quinn suggested that since we had to mask the threaded PEM nut anyway, we might as well mask it with an eyebolt and hang the part from the eyebolt so the water would drain from it. “Problem solved,” said Quinn, so back to my office I went.

It seemed like I had just dumped my cold coffee and made a fresh batch when my phone rang again. “Boss, can you take a look at this?” Quinn was sounding more frantic this time, so I rushed right down to the line. Sure enough, Quinn was standing by the oven again, shaking his head with a part in hand. “I can’t believe this. Now we’re getting pinholes and fisheyes in the top corner of the parts.”

I took the part from Quinn and scratched the area with my thumbnail. The paint flaked off easily in that upper corner. We again went back to the washer and looked at the upper corner of the wet parts. Water was beading up like rain on a fresh-waxed car (see Figure 3). Because the parts were tilting downward, the pretreatment chemical was not able to reach the upper corner. “Now what?”

“Quinn, have you still got those pinch hooks we were testing?” I asked. “This might be a good application.” Quinn grabbed a dusty box from the back room and pulled a funny-looking V-shaped hook from the box. He slid it into the hole on the part and it held tight. With the box hanging from this hook, it hung perfectly straight, allowing for full exposure and full drainage. “We’re on track now,” I said. “Now let’s pull the eyebolts and rehang these parts on the pinch hooks.”

Finally, all the problems were solved, and I could get back to my paint line design project ... but the phone rang again. “Boss, can you take a look at this?” I don’t know why I was surprised.

This time when I got to the line, Quinn was holding a part that was on a table we use for rework prep. “Look at this, boss. We tried removing the eyebolts and they won’t come out. We’ve already broken several of them.”

Several eyebolts were screwed in too far and extended beyond the PEM nuts, exposing the eyebolt threads to the powder coating (see Figure 4). The powder buildup made it impossible to remove the eyebolts. I told Quinn to get them into the chemical paint stripper. “We’ll have to strip them, remove the eyebolts, and repaint.”

At least this happened only on a portion of the parts, and the painting was going well, so now I knew I could get some work done on my project. My office was beckoning me back. I started pouring a cup of coffee and then paused to look at the phone—just anticipating. Sure enough, it rang again.

Figure 2

The part carried excess water coming out of the washer, which led to rust. The part shifted during processing, too, creating an excessive hook mark. So we masked the PEM nut and hung the piece from the eyebolt (far right).

“Boss, can you take a look at this?” Quinn sounded sad this time, so I wasted no time getting to him. “Look, boss, the parts came out of the stripper and all the PEM hardware is rusted. The stripper took the plating off, so now they’re ruined.” I tried to console Quinn, reminding him that the current painting was going well and at least we were dealing with a limited number. I agreed to call the customer and explain.

I went back to my office and took a deep breath. I knew this call was not going to be any fun. Staring at the phone, I tried to figure out a way to explain this in a way that wouldn’t make us look like complete idiots. Finally, I picked up the phone and called to tell him we destroyed his parts. Fortunately, the customer understood, but I did have to pay a premium to have the parts remade since they were critical for the order, and now it was a short run so the setup exceeded the part cost. Life lesson learned. At last the problems were over, the current painting was going well, and I could finally work on my design project.

The phone rang. “Boss, we’ve got a problem.” At least he didn’t say, “Can you take a look at this?” I asked, “What now, Quinn?”

Quinn went on, “With all that’s happened today, we didn’t get a chance to put a gap in the line for lunch. Is it OK if we stop the line with parts in the washer so we can go to lunch?”

Argh!

Ted Schreyer has spent 42 years running a large job shop coater in Minnesota and has experienced just about every finishing challenge you can imagine. He currently is president of Associated Finishing Inc., (AFI) and is co-owner of Pretreatment Equipment Manufacturing (PEM).

About the Author

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,