Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fabricate, install, maintain

Fabricator focuses on projects from cradle to grave

- By Tim Heston

- June 8, 2012

- Article

- Shop Management

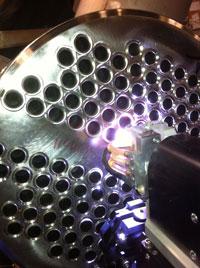

Figure 1: Roberts Co.’s fabrication team performs orbital welding on a heat exchanger. The company handles all aspects of such projects, including engineering, fabrication, delivery, and installation.

In 2009, after many years in the industrial fabrication business, Dave Staskelunas moved to The Roberts Co. as vice president of fabrication services. Many of his colleagues in senior management came onboard during the past few years as well. During this time, Roberts Co. has remained profitable even during slow times, an unusual situation for a heavy fabricator tied to the industrial construction business. Retrofit and remanufacturing were up during the downturn, because industries needed old equipment and facilities to last longer, but plant construction certainly wasn’t on a tear.

The company specializes in industrial facilities, not residential or commercial buildings, one of the epicenters of the financial bust. But Roberts still is in the construction business, and plant construction requires capital, which was in ridiculously short supply during the Great Recession.

Some aggressive investment in both people and capital came after Main Street Resources, a private equity firm, acquired Roberts in 2008. Thanks to recent events, including the career of the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, many see private equity people as efficiency experts—or as the less corporate moniker, hatchet men. Main Street reportedly doesn’t fit this stereotype. According to Staskelunas, the firm has various high-mix, low-volume manufacturers in its investment portfolio and so understands the idiosyncrasies of this complex, highly variable business.

“Even though things slowed down, we purposely continued to grow the talent pool, because when it turns around you’ve got to be ready. And the economy doesn’t stay down forever,” Staskelunas said. “We all know that.”

Those seemingly gutsy investments are paying off. In 2011 the 700-employee firm earned revenue of $108 million. At this writing, managers expected 2012 revenue to be $150 million. But the company probably wouldn’t be so successful if the founder, John Roberts, had built a more conventional organization. The Roberts Co. isn’t a heavy industrial metal fabricator. It’s not an erector, general contractor, maintenance services provider, or engineering firm. It’s all of the above.

Cradle to Grave

Company founder John Roberts didn’t set out to create such an unusual place. He launched the business in 1977 as a conventional mechanical contractor, spending his days in a truck driving to local companies to perform welding and other repair work. By the mid-1980s Roberts built a small fabrication facility in Winterville, in eastern North Carolina.

Throughout the early years the fieldwork and in-house fabrication divisions collaborated in a way that helped Roberts edge out competitors, especially those that offered just one service or the other. “If the fieldwork side of the business needed something in a relative hurry, say, for a plant shutdown over a weekend, they could call on the fabrication department. They would have the material in-house, make it, and deliver it over the weekend,” Staskelunas said. “Customers weren’t chasing around, trying to find a company that could fabricate a product quickly. We could do it in-house, immediately.”

Then customers began to request additional services, and Roberts obliged: first simple pipe welding, then pressure vessels and heat exchangers (see Figure 1), then structural supports for those pressure vessels and heat exchangers, and then finally to the fabrication of specialty materials like duplex steels, Hastelloy®, and myriad proprietary metal grades, which has become Roberts’ sweet spot.

Employees have gotten used to customers sending them secrecy agreements to sign. If someone files a patent, it’s public knowledge, available worldwide with just a few clicks, thanks to the Internet. Secrecy agreements keep innovations offline and, well, secret. (Those agreements also are why this article provides only sketchy information about specific jobs.) The company continually develops new welding procedure specifications (WPS) for unusual material. By now Roberts has more than 500 qualified, active welding procedures.

Over the years customers have requested engineering and specialty mechanical services too. Eventually they needed Roberts to help design, build, and maintain entire facilities, and this led to the company’s current incarnation: a midsized EPC (engineering, procurement, and construction) firm, but a very big industrial fabricator, erector, and construction contractor. Its bread-and-butter work includes jobs with total project costs from $25 million to $150 million.

Figure 2: To make a project as efficient as possible, field services workers collaborate with the fabrication department to ease both manufacturing and installation. Most of Roberts’ installation work occurs in the Southeast, but the company does offer field erection services nationally, such as this tower work in Arizona.

Unlike smaller industrial fabricators, Roberts can handle entire projects, and unlike large EPC firms, it claims to do so with minimal bureaucracy. Roberts Co.’s size allows the firm to tackle projects too small for multibillion-dollar EPCs. But with 700 employees, it’s not a small shop, either.

“We have nearly 50 engineers now,” Staskelunas said. “We’ve grown into a truly midrange EPC.”

The company uses its unusual size to its advantage. Its engineering division works with the fabrication division, which works with field services (see Figure 2). Everyone moves in concert to provide services throughout the project’s life cycle: design, engineering, fabrication, construction, and maintenance.

When a customer orders a vessel, Roberts may also learn that the vessel is part of a plant upgrade. That means the company at least is aware of a future project that may be coming up for bid during the months ahead.

“The company may not even be contemplating putting an [installation] job out for bid for another six to eight months,” Staskelunas said. “It gives us some market visibility.” This partially alleviates a common problem since the financial crisis not just for Roberts but for all kinds of fabricators: Customers are waiting longer to place orders. Just because Roberts may perform the vessel fabrication doesn’t mean the customer will place the on-site construction work out for bid any sooner. “But at least we know it’s coming, and we’re prepared for it,” Staskelunas said. “We’re not blindsided.”

The company’s maintenance division, which reports to the field services department, helps diversify Roberts’ revenue and rounds out its cradle-to-grave plant services strategy. Personnel handle a variety of maintenance tasks, from one-time machine maintenance and equipment rebuilds to work involving maintenance service teams based inside customer plants. From the customer’s perspective, these maintenance workers don’t act as outsourced contractors who may need regular management or guidance. Instead, they report directly to Roberts’ managers. This essentially takes maintenance duties off customers’ hands.

“These are people we are responsible for, so we should be the ones who manage them,” Staskelunas said.

Ham and Egg

“We ham and egg it really well together,” Staskelunas said.

The egg has to be fried just so, the ham cooked to a certain temperature, and then both put on the plate at exactly the right time. That’s easy for a short-order cook, but not so easy for those who manage projects with hundreds of workers having diverse specialties. To work in concert requires some good conducting.

When any project comes up for bid—be it for a vessel, a construction job, or a comprehensive EPC contract—the company team bids carefully. If a job has a prebid meeting at the customer’s facility or job site, Roberts’ managers will be there. The quoting process is very detail-oriented. Estimators may call the customer to request clarifications and suggest alternatives, and the company has built a database of time logs and hourly cost structures over the years.

Figure 3: Roberts opened its new, 90,000-sq.-ft. fabrication facility in 2011. The facility handles most of the company’s specialty material work, including duplex and superduplex metals.

“We try not to estimate,” Staskelunas said. “You’ve got to be able to know your true costs. No one likes surprises, and no one likes change orders.”

He conceded that this approach sometimes prevents the company from winning bids, simply because the quote includes every element involved in the order—again, to avoid those surprises in the middle of the job. It also fosters pragmatism and honesty. The company focuses on complex projects involving unusual materials and comprehensive service, including engineering and field erection. Personnel will quote simple vessel work if asked, of course, but the company often tells prospects that its quote probably won’t be the most competitive for the job.

“We tell them that other companies may be a better fit for the job,” Staskelunas said. “That’s doing a service for customers, and many times they remember it.”

Scheduling Strategy

With so many employees performing such diverse work, inaccurate quoting would make already complex projects even more so. After a bid is won, Roberts’ centralized administrative group assigns each job a number that incorporates the date as well as a suffix that signifies which division will handle the job, be it engineering, fabrication, or field services. The choice hinges on whichever division will add the most value for the job.

Say a complex pressure vessel requires extensive planning and perhaps even a few more WPSs to add to Roberts’ already vast library of procedures. For this job, the fabrication operation will become the lead and other divisions will play the role of a subcontractor. Conversely, if a project involves complex erection, the field services team will become lead, the fabrication division the subcontractor.

It is typical practice for structural fabricators to simplify field erection by bringing more fabrication in-house, a controllable environment. They attempt to assemble more parts under their roof so that the erection team doesn’t have to perform as many picks on the job site. But because both on-site and field fabrication experts work together at Roberts, the team thinks broadly. Sometimes more in-house fabrication isn’t necessarily easier, especially if it becomes a bear to transport, pick, and position parts into the structure on-site. Crane pick distances and other on-site erection considerations come into play. The fabrication shop may well choose to fabricate a structural element in smaller pieces that are easier to transport and position, even if it complicates on-site fabrication and erection.

Project-centered Fabrication

Roberts now has two fabrication facilities, one at its Winterville headquarters and another recently opened, 90,000-square-foot shop a mile and a half away. Primary fabrication equipment—including an 800-amp plasma cutting table, 10-foot-wide plate rolls, and press brakes—remains at the Winterville facility, which also has blast and paint booths (see Figures 3-5).

“We tend to do carbon steel or anything else that needs a protective coating at that [Winterville] facility, so the products are right there for the blast and paint booths,” Staskelunas said. “In the new facility, we tend to do a lot of our high-alloy work that doesn’t need coating, so the work can ship directly from there.”

Like in the sheet metal job shop world, some periods are busier than others. Say the field erection crew needs a pipe spool for installing power piping, but the in-house fabrication group is slammed with complex vessel work. “So the field services division might send a few workers to the [fabrication] shop to make those pipe spools for a job in the field,” Staskelunas said.

Field workers visit the fabrication operations frequently, not only to perform some basic fabrication when needed, but also to keep abreast of any new capabilities the shop might have. Conversely, shop personnel visit job sites to gain a grasp of standard field erection practices.

Figure 4: The company’s primary fabrication equipment, including its plate rolls, remains in the Winterville facility. Because the original plant has blasting and paint booths, it handles most of the company’s carbon steel work.

The approach is a bit like some of the “patient-centered” initiatives that have made health care headlines in recent years. Say a general internist sends a patient off to a specialist. That specialist prescribes pills that cause an unexpected reaction, which could have been avoided with adequate medical records, and especially if that specialist and internist had simply talked to each other over the phone or, even better, in the same room with the patient.

In this sense, Roberts takes a project-centered approach and has all experts in the same room, or at least on the same page. Employees do work where needed to keep production on schedule, healthy and profitable—with no adverse reactions.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI