CEO

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Free the sales bottleneck in metal fabrication with balance

A successful shop needs a sales department equal parts prospecting (hunting) and account management (farming)

- By Anthony M. Colarusso

- February 17, 2021

- Article

- Shop Management

A shop with immense fabrication power won’t grow revenue if salespeople don’t have time to land new accounts and feed the shop more work. They’re too busy being farmers to be successful hunters. To grow, a fabricator needs both. Getty Images

“Matthew Howell!” George Peterson’s voice boomed from down the barren hallway.

Matt couldn’t imagine what this was about. He had just completed implementing a manufacturing execution system (MES). It was a huge success and every aspect had been thoroughly tested and proven over the past two weeks. The plant had more manufacturing capacity than ever before.

“Coming, Mr. Peterson,” Matt shouted as he grabbed a notepad and pen. What did I get myself into? Timidly, he entered Peterson’s office.

“Matt, I gotta be honest with you. The MES has been a huge success. With all of the visibility and efficiency from your system, we have nearly doubled our available production capacity.

“Still, we have a problem,” Peterson continued, looking over his glasses. “You see, if you zoom out of any business, it really just consists of two parts, sales and production.”

“Yes, I suppose that makes sense.” Matt pondered the oversimplified concept. “Sales will drive what comes into production, and then production makes whatever sales can close.”

“You got it. So we just made a massive investment in MES and nearly doubled production capacity,” Peterson reminded him. “So, what is our problem?”

Matt thought of the theory of constraints, which says that any manageable system is limited in achieving its goals by a very small number of constraints—and at present he knew that production wasn’t one of them.

“So if our goal is to grow Peterson Manufacturing, a business consisting of two parts—sales and production—and production capacity has increased significantly, then our constraint must be sales,” Matt said.

“Yes,” Peterson replied. “We have a sales problem, Matt. Heck, one of our estimators is just sitting idle. I need you to fix it.”

Similar to production, sales prospecting (hunting) requires defined processes, division of labor, and tracking mechanisms at each stage. A CRM can be used to load prospects that can be prequalified (scored), decision-makers can be linked, and sales actions can be tracked. Getty Images

Trying to Do It All

Matt had spent most of his career in production, and now he was being tasked to fix sales? The sales function seemed to be a black box from which orders just, well, emerged. To learn more, he needed to talk to Bill Henderson, the company’s chief (and only) salesperson.

First, for some perspective—and to see how the new MES was faring—Matt walked to the shop floor. He saw receiving personnel inspecting raw material and recording information into the MES. He saw that same raw material loaded into the laser. When the parts emerged, employees sorted them into designated carts and applied job-specific bar codes before the carts were pushed downstream to the press brakes. Scan, deburr; scan, bend; scan, hang for powder coating; scan, assemble; scan, package and ship. Every step built upon the next: Quality laser cutting made bending easier; proper bending ensured ease of assembly.

Matt’s thoughts then turned to Bill. During lunch breaks and water cooler chats, he learned that Bill liked to prospect for new customers—to “hunt,” as he called it—but couldn’t spend much time doing it. He spent a good part of his day taking care of current customers. Pulled in all directions, he tried to do it all: research markets, prospect potential customers, and serve current ones.

Matt stopped walking and watched a fabrication cell dedicated to a product family. He imagined Bill inspecting incoming material, then running every machine in the cell—the punch press, the brake, the hardware press, the spot welder—all on his own. How productive would that cell be?

Matt turned toward the door that led to the front office. He had an idea, and he wondered what Bill would say.

The Sales Problem

“Bill, I’ll be honest ... I don’t know the first thing about sales.”

It was several days later, and Matt, sitting in a coffee shop booth across the table from Bill, figured he might as well be honest.

The sales chief chuckled. “No kidding.”

Matt sat holding his coffee with both hands. “Peterson has asked me to get involved, and I think I can help.”

“OK. What do you have in mind?”

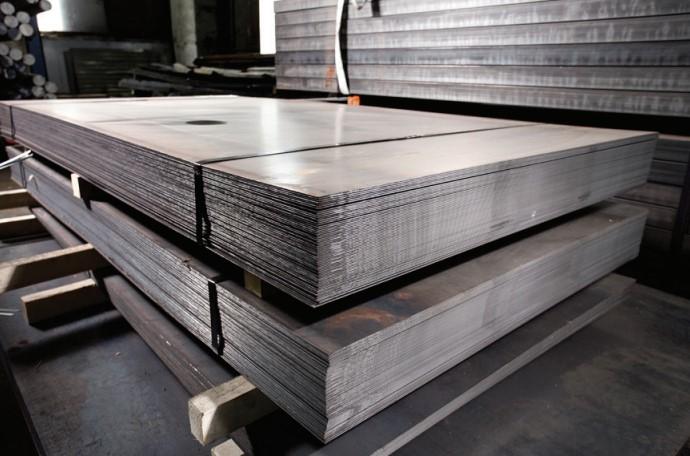

A list of qualified prospects is analogous to inspected and verified sheet metal at a fabricator’s receiving dock. Getty Images

“Well,” Matt carefully proceeded, considering how silly it would sound. “We need to … fabricate sales.”

“What? Fabricate sales? Look, I’m an honest guy …”

“No, no, no,” Matt cut him off. “I don’t mean we need to lie about sales. We need to figure out how to put each prospect through a process, just like the way material flows through manufacturing.”

Bill looked confused.

“Where do you get your prospect list from, Bill?”

“I download lists from a source online.”

“OK, that is your raw material,” Matt said. “Imagine each row of the Excel sheet is like a sheet of metal.”

“I suppose that makes sense.” Bill raised his eyebrows.

“So then what happens?”

“I call down the list. I can call up to 100 in a day, but only if I’m not interrupted by a current customer. I call all the way down the list, then start back at the top. After three passes, I toss the sheet and then download another one.”

Matt began making some notes on the notepad in front of him. “So, you have a list of 500 prospects. That should last you about three weeks. How many would you guess buy fabrications at some time throughout the year?”

Bill sat up in his chair. “I guess I never thought about it that way. I usually just ask if they are quoting anything right now. I would say if the list is any good, about half buy fabrications on some level. Some will buy a lot more than others.”

“Exactly,” Matt jumped in. “That is what I mean by qualified. Bill, you are going through the list of 500 three times, but only 250 even have the potential to be customers at any given time. But what if you batch your actions, just like we do in manufacturing? We have receiving, cutting, bending, coating, and shipping. Each area has a process and skilled operators that perform specific actions.”

“So are you saying I’m not a skilled operator?”

“No, that’s not it at all,” Matt clarified. “I’m saying you need to divide the labor at each step of the sales process. Your ‘receiving area’ is when you download that list. You need to verify and validate your lists. Effectively, you need to prequalify them. How long would it take you to open all 500 websites and assign a score?”

“A score?” Bill asked.

“Yeah, just something simple, like A B C D. An ‘A’ account is excellent, with the potential to fit into the top 20% of our business. A ‘D’ account is disqualified. ‘C’ is small, but we would take it. ‘B’ is the bell curve of our business, an average customer.”

“Doing that 500 times would take me all day, I would think. Probably around eight hours.”

“That’s what you’re going to do all day on Monday,” Matt said with confidence. “You need to put a process around ‘receiving,’ where you verify and validate your lists. Once you go through and validate that list of 500 once, you might eliminate half. That means it’s going to save you two and a half days of work each time you work the list.

“Now,” Matt continued, “when you call, whom do you speak with?”

“Well, usually a gatekeeper answers,” Bill replied. “A receptionist or something. I ask them if they have any fabrications for me to quote.”

“When you talk with the decision-maker, are you more likely to find work?”

“Sure. Problem is, most of the lists don’t come with contact data. If I don’t have a name, I can’t get through.”

“Here is what I want you to do on Tuesday, Bill.” Matt took a sip of his coffee with one hand while making notes with the other. “You’re going to call through that prequalified list of 250 and ask who is responsible for working with outside fabricators like Peterson Manufacturing. If you’re just asking that question, not selling, how many of the 250 could you get through on Tuesday? Especially if you aren’t interrupted?” Matt asked. “Think of this as your fabrication process. You’re adding value to the raw material—your verified list—by cutting blanks.”

“I would say … I could get through to all of them. That doesn’t sound so bad. I could actually use LinkedIn to get some names.”

“Sounds like a plan, Bill. So by Tuesday afternoon, you will have narrowed the list and identified all the decision-makers. Now, you currently call the list three times and then toss it?”

“That’s right. I move on to a new list.”

“You’re not going to do that anymore. Since you prequalified those 250 accounts, I want you to nurture them. Eventually something will happen in their supply chain, and you will find an opportunity.”

“So I never let them go?”

“Well, let’s not jump to that,” Matt replied. “I want you to start tracking the calls you make on the list of 250. We can measure how many attempts it takes to reach a decision-maker, and then how many conversations yield a meeting.”

“You mean I should track the actions in the CRM?”

“A what?” Matt asked.

Bill smiled, having identified something Matt didn’t know. “Our customer relationship management system. Think of it like an MES, but for sales. Every email, sales call, and request for quote can be recorded.”

“That’s perfect, Bill,” Matt exclaimed. “By tracking everything, we gain visibility. By keeping in touch, you continue to add value to each account, just like we do by forming on a press brake or powder coating a component.”

“How are you going to keep current customers from bothering me?” Bill asked.

“I’ll take care of that.”

In Practice

On Monday morning Bill got to work validating and verifying a list of 500 contacts. Matt set a meeting with Peterson and pitched him the idea of shifting the idle estimator to handle existing customer requests. This would offer the customer a dedicated contact, freeing Bill to hunt for new customers.

On Tuesday Matt popped into Bill’s office. “How’s it coming along, Bill?”

“255 accounts verified and validated!” Bill said, beaming. “I have 40 labeled as A accounts, 150 as B accounts, and 65 C accounts.”

“Excellent!”

“I’d love to keep talking, but I gotta start cutting blanks,” Bill said with a smile.

Wednesday morning Matt checked in with Bill again, who was already calling through the list of prequalified accounts.

“I plan to call twice in the first week, followed by an email,” Bill said. “If I don’t get a response, I’ll continue a cadence of contact every four to six weeks to follow up.”

“That’s great, Bill,” Matt replied. “That process ensures you’re always ahead of the next project.”

“I’ll prioritize the A and B accounts. They get contacted more often, while the C accounts get called maybe quarterly,” Bill said. “Rather than hunting for an RFQ, I’m asking if they would be interested in a discovery meeting.”

Matt nodded, thinking that discovery meeting was, in essence, a value-adding step in the sales process, much like bending or powder coating in the plant. Scheduling those meetings is one of the many steps required between qualifying a prospect (again, akin to inspecting and verifying raw material) and winning an order—turning that prospect into a paying customer.

The Payoff

After three months, Bill transitioned all of his current customers to the previously idle estimator, who in turn was able to grow those accounts quickly. Bill called this “farming,” tending the crop of current customers.

At this point Bill didn’t farm but instead devoted most of his days to hunting for new prospects. On average, he made seven attempts to reach a decision-maker, and he often pushed for a meeting before quoting. This way he could sell value to the account and build trust over time before transitioning the account over to a dedicated customer support person.

Process Matters

On the production side, most fabricators develop dedicated processes, train operators, and adopt robust tracking mechanisms that provide visibility and costing down to the millisecond and penny.

But what about the sales side? After all, according to the theory of constraints, a business will not grow until sales meets or exceeds the level of production.

Fabricators often track salespeople only by what they close. Furthermore, salespeople often continue to manage the customers they close. In this model, a successful salesperson is destined to become a mediocre account manager. By allowing for the division of labor in the sales process, a hunter (prospector) can continue hunting, and the inside team can farm—manage and grow existing accounts.

Similar to production, sales prospecting (hunting) requires defined processes, division of labor, and tracking mechanisms at each stage. A CRM can be used to load prospects that can be prequalified (scored), decision-makers can be linked, and sales actions can be tracked.

A shop with immense fabrication power won’t grow revenue if salespeople don’t have time to land new accounts and feed the shop more work. They’re too busy being farmers to be successful hunters. To grow, a fabricator needs both.

About the Author

Anthony M. Colarusso

6657 W. Ottawa Ave. Unit D2

Littleton, CO 80128

(419)-702-0683

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 05/07/2024

- Running Time:

- 67:38

Patrick Brunken, VP of Addison Machine Engineering, joins The Fabricator Podcast to talk about the tube and pipe...

- Trending Articles

Young fabricators ready to step forward at family shop

Material handling automation moves forward at MODEX

A deep dive into a bleeding-edge automation strategy in metal fabrication

White House considers China tariff increases on materials

BZI opens Iron Depot store in Utah

- Industry Events

Laser Welding Certificate Course

- May 7 - August 6, 2024

- Farmington Hills, IL

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,