Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Hot rod origins, metal fabrication future

How a hot rod shop became a growing manufacturer

- By Tim Heston

- August 2, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

This is the interior of an aftermarket stainless steel exhaust system from Stainless Works. Being first to market with several products has given the company a competitive advantage.

Greg Fuller remembers his father’s long nights in the shop. Ron Fuller, a former shop teacher with a lifelong interest in restoring cars, had launched Classic Auto Works in 1987. As its name suggested, the company focused on restoring classic cars and hot rods, from Model Ts to early roadsters—a competitive market, for sure, and one driven by people with passion for the work.

Ron loved the work too, but those late nights spent alone after the crew had gone home began to get old. In the early 1990s he purchased the assets of a bankrupt shop called Classic Stainless. As Greg recalled, “It wasn’t much of a company. What he really bought was the right to use a couple of fixtures, a few patterns, and a tube bender. The company produced a handful of products for older Chevrolets, products we don’t even sell today.”

Still, buying that tube bender changed the course of the company’s future. What was once a hot rod shop now is Stainless Works, a growing automotive aftermarket manufacturer with a custom metal fabrication subsidiary, MetalFab Group. The 50 employees of the Chagrin Falls, Ohio, organization will be moving into a new, 65,000-square-foot building later this year, with two acres to spare for future expansion.

Becoming a Manufacturer

Working on hot rods is a labor of love, and this certainly was the case for Ron Fuller. He even won the Don Ridler Memorial Award for excellence in building during one Detroit Autorama hot rod show. Still, time, labor, and component costs varied substantially from project to project, with unexpected challenges turning up regularly, often at the worst possible times. It would have made good drama for reality TV (had that been around at the time), but the situation wasn’t the easiest for creating a sustainable, growing business.

After the shop invested in its first tube bender, though, its focus changed, and a transition soon was underway.

As Greg Fuller explained, “This is when [Ron] began the transition to a manufacturing company, what is today Stainless Works. He did some restoration work [in the 1990s], but his main focus was the manufacturing. By 1999, he restored his last hot rod, and all resources were focused on manufacturing.”

Instead of building classic hot rods, the company, doing business under the Stainless Works name, launched its own lines of aftermarket stainless steel exhaust products. These would evolve to include exhaust products not only for classic cars, but also late-model ones.

As Heath Kohler, national sales manager, recalled, “When the company transitioned to exhaust component manufacturing, it was just an eight- to 10-person operation. The company founder was smart enough to realize that if he focused on component manufacturing, he could figure out the fixed costs fairly easily. If you have one setup and you can build 20 systems at a time, you’re amortizing the [setup] costs across the run.”

Like many small shops, Stainless Works began its component manufacturing using the resources it had available, which at first wasn’t much. But by the early 2000s its growth really stepped into high gear. The shop hired an engineering team and built a process for quick product development. This quick response was the keystone to Stainless Works’ early success; the automotive component aftermarket rewards those who are first to market with a product. Using touch probes and other tools to establish datum points, and using that information to establish the tube bending program, the team builds a prototype as quickly as it can.

Stainless Works developed relationships with local car dealers. As Greg Fuller, now sales engineer, explained, “Our engineers and R&D personnel design an exhaust system that provides the best air flow and best sound. That’s what everybody’s looking for: sound and performance.”

A large sheet is staged for bending at the press brake. MetalFab Group is increasingly getting into large assemblies.

“The exhaust system is made out of 304 stainless steel, so it’s going to last for 100 years,” Kohler said. “The car will be long gone before the exhaust system wears out.”

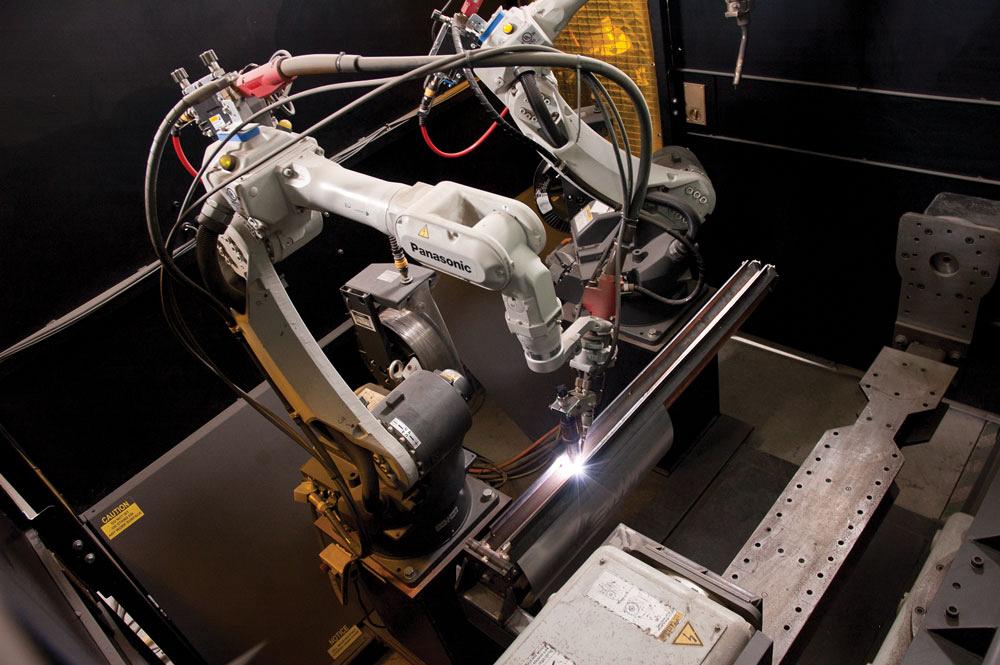

The company moved early into welding automation. A decade ago it purchased a welding cell with two articulating robot arms, one with a gas metal arc welding (GMAW) gun and one with a wire-fed gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) torch.

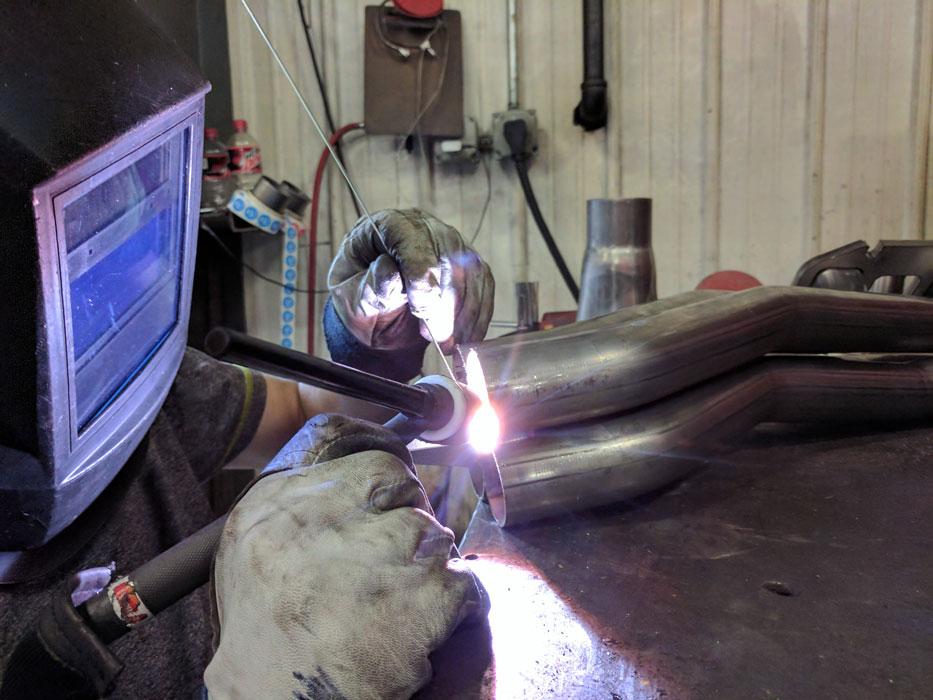

“We were an early adopter in our area for automated GTAW,” Kohler recalled, adding that GTAW was a good fit for a few of the shop’s higher-run stainless product lines. The thinking was that making the same weld all day, even with GTAW, wouldn’t take full advantage of the company’s welding talent, which now focuses mostly on lower-volume work.

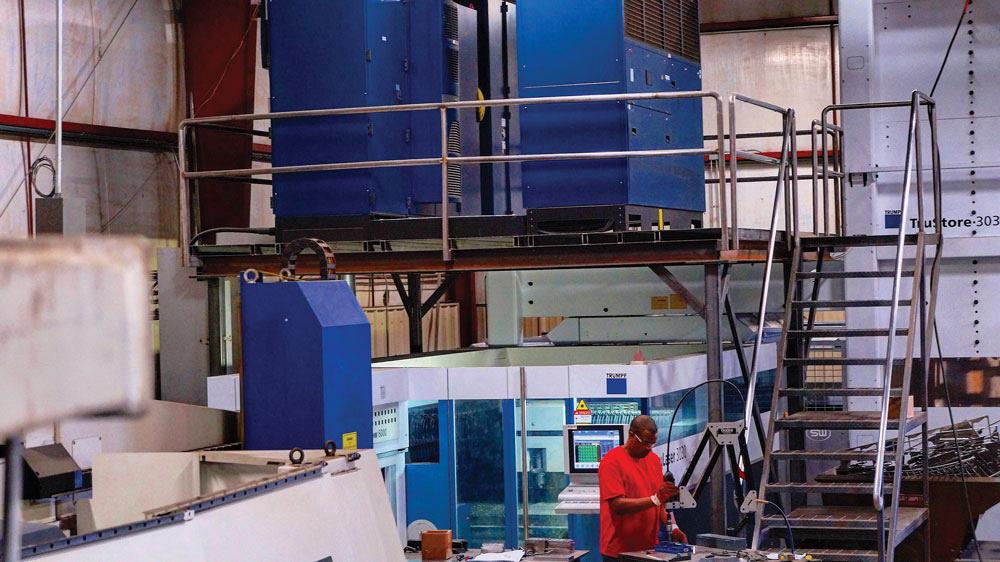

To cut its own flanges for the exhaust components, the company purchased its first laser cutting system in the early 2000s, followed by a second system in 2006. It then replaced its first laser with an automated material handling tower in 2013. When the shop wasn’t cutting flanges for its own product lines, it cut flat laser parts for other local companies.

Going Custom

Of course, the flat laser cutting market got crowded in a hurry. With nearly every fabricator in the area owning a laser, flat laser cutting by itself was becoming a commodity. So in 2005 it upgraded its bending capability with a new TRUMPF press brake that, combined with its existing welding capability, allowed the manufacture of complete sheet metal assemblies.

“The owner [Ron Fuller] at the time had the foresight not to put all of his eggs in one basket, with the Stainless Works brand,” Kohler said. “After all, with trends in emissions, is aftermarket exhaust manufacturing going to be viable in 20 years? On the other hand, there’s always going to be a need for custom fabrication.”

This led to what became MetalFab Group, a subsidiary officially formed in 2013. Today the custom fabrication operation processes everything from small pieces to large sheet and tubular assemblies, including fabrications made of food-grade material.

Exploration

Launching MetalFab Group helped overcome two fundamental challenges. First, selling custom fabrication under the Stainless Works brand made people assume that the company specialized only in stainless steel, which wasn’t the case. It’s the reason MetalFab Group’s website prominently lists a range of materials the company works with, from carbon steel to titanium.

The second challenge was commoditization. Answer a request for quote and do nothing else, and it can become just about the price. For this reason, MetalFab Group has instituted an “exploration” step, spelled out in detail on the company’s website and other marketing material. It all boils down to four steps: exploration, quoting, ordering, and production.

The company’s laser cutting system is shared between Stainless Works and MetalFab Group. Note the space constraints. The company is moving into a new facility later this year.

“During exploration, we want to look at the job in depth,” Kohler said.

Sales engineers ask questions about specified tolerances (or lack thereof), and generally discuss how they can save customers money while maintaining or improving quality. It’s a common practice among fabricators these days, though documenting it in marketing material helps set the fabricator apart, especially for prospects unfamiliar with sheet metal.

Internal documentation detailing exploration, quoting, and estimating (and every other shop process, for that matter) helped the company attain ISO 9001 certification in January of this year. The company originally worked toward ISO certification for the MetalFab Group subsidiary, considering many original equipment manufacturers in the market require it. But because processes were documented on both the custom fabrication side and the automotive aftermarket side, Stainless Works attained ISO certification as well—and as of this writing, it remains one of the few aftermarket stainless steel exhaust manufacturers to do so.

The organization had the growing pains many small companies experience. Early on the shop’s handful of employees wore multiple hats and just did what it took to get a job done. The shop had a lot of holdovers from its hot rod days.

Now, instead of working off hand-drawn prints, workers refer to standardized work instructions and blueprints. The company now has an engineering and sales staff, as well as a marketing team that has successfully gotten the Stainless Works name into various media outlets. Watch the Discovery Channel’s “Street Outlaws”, and you’ll see cars with exhaust systems from Stainless Works. In fact, having the Stainless Works brand has helped the company gain the broad recognition that a typical custom fabricator couldn’t achieve. All the same, a good marketing opportunity on its own doesn’t make a sustainable business—hence the need to diversify beyond the automotive aftermarket with MetalFab Group.

Two Businesses, Too Many Doors

Having two businesses under one roof is now baked into the metal manufacturer’s long-term strategy. It employs two production managers who juggle the resources the two businesses share, including laser cutting, bending, and robotic welding. The flow then splits into two separate value streams at manual welding and assembly.

The current building has been expanded six times. The original hot rod shop now is the shipping department; you can still see the checkered black-and-white stripe around the perimeter—still appropriate, considering the shipping department is the finish line of production.

Although exhaust products and other sheet metal assemblies cross the finish line, the race to the checkered flag could be smoother. Sources explained that achieving smooth part flow can be challenging, and not because the shop lacks good planning. It just lacks the right facility.

“It’s so chopped up,” Kohler said. “I swear that I’ll walk around a corner and find yet another door that I didn’t even know was there. It’s very departmentalized.”

Hence the strategy of moving to a 65,000-sq.-ft. building with several acres to spare for future expansion—room for an entirely separate factory dedicated to one business, either Stainless Works or MetalFab Group. The thinking is that in the future, while the two organizations would continue to share ideas and collaborate when it makes sense to do so, they would share few if any resources for production.

The company employs 15 welders, all of whom know the gas tungsten arc process. Manual welders work solely with either the Stainless Works product lines or with make-to-order assemblies for MetalFab Group.

When the companies move to their new facility in November, though, they will continue to share fabrication and automated welding equipment. But with the open layout, flow will be much smoother, and workers will have much better lines of sight. People will know where jobs are coming from and where they’re going.

Although layout is in its early stages, as of now the company plans to have the flow start on one side of the facility, with shared laser cutting, press brake bending, and automated welding. Flow will split into separate manual welding and assembly areas dedicated to either Stainless Works or MetalFab Group, and then come back together again at the shipping department.

Handling the Growth

It’s not unusual for a fabricator to grow to, say, $10 million in annual revenue and then falter a bit operationally, particularly if sales growth remains rapid. The shop gets too large for muscling jobs through without established, agreed-upon, and documented processes.

This situation wouldn’t be surprising at Stainless Works and MetalFab Group. After all, both sides of the business continue to grow rapidly. Year-end revenue in 2016 was $6.5 million, and projected revenue for 2017 is $8 million. The company expects custom fabrication to grow 50 percent this year and the automotive aftermarket business to grow 30 percent.

So are employees feeling the growing pains now?

“Not really,” Kohler said. “We have ISO certification and process documentation. And yes, when we grow past $10 million, we know that any company becomes more difficult to manage, and at some point, we’ll break the two companies apart.

“But we’re ready. In fact, when it comes to growing pains, by far the biggest pain was going from $500,000 to $5 million [in annual revenue]. Back then, the [Stainless Works] branding was really starting to take off, and we needed to find the right skilled people to make the products.”

“We took a step back, looked at our operating procedures, and really dialed those in,” Fuller added.

Kohler jumped in with a coda about the company’s plans to add fabrication capacity, including a fiber laser. He added that modern equipment, combined with refined, documented processes, will help the business scale up to the next level. “Right now, to get to $10 million, to be honest, we don’t have to add that many more people to get there.”

If the company were still restoring hot rods, Kohler probably couldn’t have made that statement.

Photos courtesy of Stainless Works, 800-878-3635, www.stainlessworks.net; and

MetalFab Group, 440-543-6234, www.metalfabgroup.com.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,