Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The three layers of a metal manufacturer’s growth

How NSA Industries became one of the largest fabricators in northern New England

- By Tim Heston

- May 31, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

A $42 million custom fabricator, machine shop, and assembler in the woods of northern New England, NSA Industries began in 1982 as a very different organization. The St. Johnsbury, Vt., company was launched as a contract manufacturer for Troy, N.Y.-based Garden Way Carts. Business grew at a steady clip until several years later, when Garden Way moved production to Taiwan. Austin was then stuck with a shear, a press brake, a powder coating line—and a declining business.

“From that moment forward, the founder knew he needed to build the company to prevent this from ever happening again. That’s when we started to diversify. He knew he couldn’t depend on just one customer.”

So said Matt Smith, NSA’s vice president of sales and marketing. Smith started with the company in 1988, back when the shop employed 12 people. Five years later the head count had grown to 60, and by 2000 it had nearly 300 employees.

Diversification tells only part of the story, though. NSA’s growth narrative has three layers. Customer and equipment diversification is one layer; customer and employee engagement is another; and at the bottom, the foundational layer, is a strong sense of place.

Community

Succession can be critical in metal fabrication, particularly if the founder’s family isn’t interested in keeping an ownership stake. It’s a common story: A family owner sells to investors who either want to flip the company for a profit or try to fit it into a larger organization. The shop becomes a chess piece in the middle of a larger game.

But what’s often forgotten is that sense of place. A company may compete globally, but it manufactures locally, and community roots are important. When the company founder decided to retire in 2007, he sold to a group of local investors who wanted to keep jobs in the area.

“When they purchased the business, they all had interests in Vermont,” Smith said. “They believed in Vermont, believed in keeping jobs in Vermont, and wanted to see manufacturing be sustained in Vermont. And they’ve been extremely supportive over the years.”

This didn’t make NSA immune to business realities. It laid off nearly a third of its workforce during the Great Recession. This was a new experience for the company, considering the dot-com crash in 2001 didn’t really affect NSA’s major customers (a rare situation at the time for a New England fabricator).

“We survived the Great Recession,” Smith said. “It was ugly and sad for all of us. But we came out of it by doubling down on everything, from continuous improvement to automation.”

Diversification

Today those 100 jobs are back and then some, and over the past five years the company has invested $13 million in equipment, including new investments in cutting, bending, and automated welding.

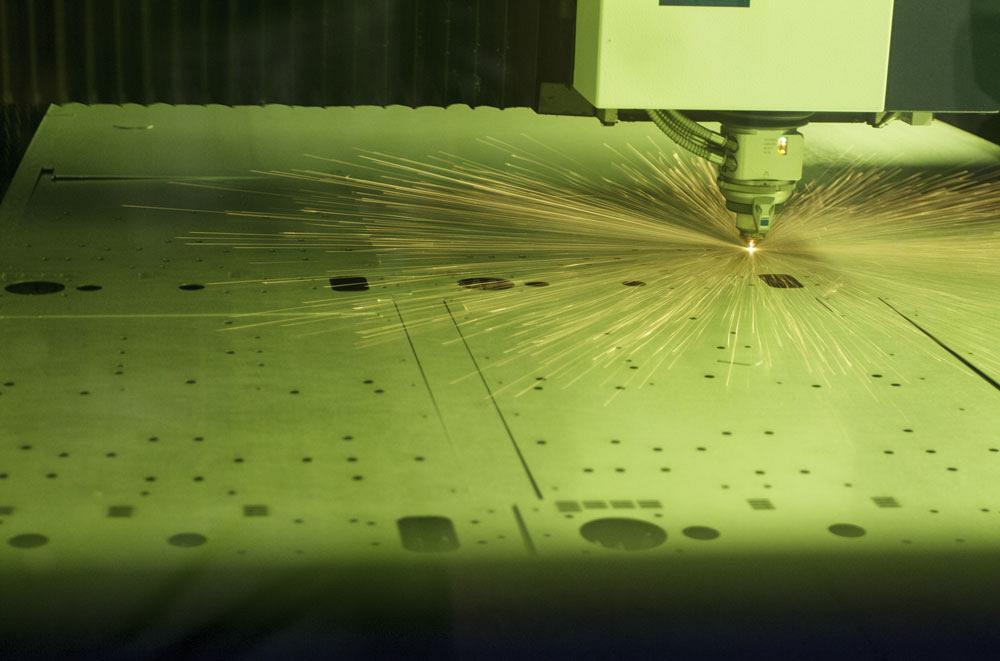

NSA has invested heavily in automation in fabrication, especially in cutting, where processes can run unattended.

The impetus for the investment came in 2012 with the purchase of an 87,000-square-foot facility a mile down the road from the original plant, which NSA was leasing at the time. The company closed on the real estate deal, then began populating it with new equipment, including a solid-state TRUMPF laser (NSA became an early adopter of 1-micron, high-brightness laser cutting) and punch/laser combination machine with load/unload automation for unattended operation. It also installed several new TRUMPF press brakes.

It was all installed in the new building over several months as old equipment in the previous facility continued producing, with no significant delays of orders. In 2014 NSA also acquired and renovated its old 84,000-sq.-ft. building it previously leased, and filled half of it with milling and turning equipment, including Swiss turn machines and several automated horizontal CNC mills.

The focus on machining goes back to the company’s early days. Shortly after losing business to Taiwan, the founder didn’t increase fabrication capabilities. Instead, he dove immediately into machining by buying a CNC vertical mill and a turning center. He soon picked up machining work, which eventually dovetailed into assemblies that included both fabricated and machined components, fastened or welded together.

The lion’s share of company growth during these earlier days came from five major accounts, all of which are still with the company today. “We were fortunate to have our top five customers grow,” Smith said. “And we grew with them.”

One customer is in the lawn and garden sector, another produces exercise equipment—two sectors that complement one another. People tend to buy lawn equipment in the spring and summer, exercise equipment in the fall and winter. “The seasonality of those two sectors stayed even,” Smith added. “Our revenue month to month stayed somewhat level. We still don’t have a lot of ups and downs. And I attribute that to the fact that our customer base is what it is.”

Some of NSA’s customers are diverse themselves, serving many different markets. Others are in industries that are simply less volatile than, say, oil and gas or other commodity-related businesses. “One of our big customers is in the food processing sector,” Smith said, adding that the product isn’t likely to become obsolete anytime soon. “Guess what? People are always going to eat. And back in 2009, two big food service companies carried us through that year.”

Once the founder sold the business to investors, the company’s growth philosophy changed. As Smith recalled, “One of our board members told us, ‘If you’re not investing in technology every year, you’re going to be left behind. You may be OK for a few years. But you’ll eventually start losing your competitive edge.’”

Ever since, NSA has planned to spend at least

$1 million in capital, either replacing old equipment or expanding capabilities with new technologies. The company obviously has spent much more than this since 2012, but the benchmark remains for future years. Investing in technology isn’t a luxury. It’s now viewed as necessary to sustain the business.

In 2012 NSA was an early adopter of solid-state laser cutting, which really made a difference considering the amount of thin stock the fabrication shop runs. “There weren’t many [disk or fiber cutting lasers] in the market, certainly in our area,” Smith said. “When you’re cutting 16 gauge at 1,000 inches per minute versus 250 inches per minute [with the previous CO2 laser], it was hard for anybody to compete.”

In the woods of northern Vermont, NSA Industries has grown to become one of the largest metal fabricators and machine shops in northern New England.

He added that, of course, this edge never lasts—hence the reason for the company’s goal of continual technology investment.

When NSA expanded into its machining facility in 2014, it had about 40,000 sq. ft. to spare. “That’s also been our philosophy,” Smith said. Being in rural Vermont, NSA can’t rely on adequate industrial space being immediately available, and building a new facility takes time. “When the next opportunity arises, we want to be able to jump on it, and that requires space. We’ve always tried to keep extra square footage available.”

He mentioned one private label job in which NSA handles all the manufacturing and logistics, from raw stock to final assembly and packaging, shipped and labeled under the customer’s brand. This job started small, but in 2016 the customer needed to ramp up volumes.

To meet this demand, NSA invested in another solid-state TRUMPF laser, two Salvagnini panel benders, three Amada press brakes, plus a robotic welding system, all dedicated to one customer. All of this was arranged as a factory-within-a-factory in that empty 40,000 sq. ft. of NSA’s machining facility.

This all happened during the spring of 2016, after which more jobs came in the door—eating up space. Then in August an opportunity arose to buy New Hampshire Precision Metal Fabricators in Londonderry, N.H., a deal that did not include the fabricator’s existing facility. “We knew we needed to absorb the new company into our existing plants,” Smith said.

This worked well for the short term, but it also consumed all the remaining available space. After working with a local nonprofit, NSA found Groveton, N.H., an old paper mill town 45 minutes away with empty and available facilities and an underemployed population.

NSA leased 72,000 sq. ft. in Groveton and moved the entire factory-within-a-factory there. Managers also have plans to add other products from other customers to that facility, increasing capacity as demand dictates. And today NSA again has space available in Vermont for future expansion.

Growth Strategy

Why did NSA purchase the New Hampshire fabricator in the first place? In a phrase, the customer base. “Organic growth is difficult,” Smith said.

Industry data backs up this claim. According to the 2016 “Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey” from the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, a typical fabricator’s new customers provide only 6 percent of overall sales. It takes time for a new customer to turn into a major account.

Smith added that organic growth has always been on the table; it just takes time. To diversify its revenue streams, NSA has launched several product lines of its own, including Carts Vermont (carts for residential lawn care) and the Driveway Groomer™ for smoothing out gravel driveways and parking lots, a common practice in rural Vermont.

Part of its $13 million capital expansion over the past year, NSA has added A robotic welding trunnion cell.

But potential for more organic growth in custom manufacturing is there. NSA serves a small geographic area, considering the company’s size. Its customers are in Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Compared to New England as a whole, northern Vermont has a relatively low cost of doing business.

“Our structure makes us very competitive,” Smith said, adding that the company’s location may help reduce shipping costs for potential clients outside of New England. “All sorts of freight is trying to get into New England, but not much leaving.”

That said, more acquisitions may well be in NSA’s future, considering the number of small family-run fabricators and machine shops in the region with owners getting ready to retire.

“We’ve seen opportunities, a lot of them beginning with strategic partnerships,” Smith said.

If a problem arises, be it capacity-related or otherwise, NSA has a network of area shops that can take on the work, and vice versa. In recent years, some (though certainly not all) of those strategic partnerships have led to acquisition opportunities, including the most recent one in New Hampshire.

Selling both extensive fabrication and machining capabilities presents certain opportunities. For instance, a recent job required cut tubes to have holes drilled to a tight tolerance. Today NSA has moved those jobs to its tube laser, which cuts the holes to well within specified tolerances.

“Sending the tube to milling extended our lead time by a week or more,” Smith said. “Now it comes off the laser and can be welded [to other components in the subassembly] that same day.”

Cross-Training

NSA cross trains heavily within and between departments. For a high-product-mix operation, it’s a necessity. And offline programming software (like 3-D CAM simulation software) makes cross-training easier. Every morning each department in each facility has a meeting to talk about where the bottlenecks are. To relieve those bottlenecks, machinists visit the fabrication shop and fabricators visit the machine shop.

Cross-training also brings about opportunities for people wanting a change to their daily routine. For instance, when NSA landed a large fabrication job with its own lean assembly cell, six machinists were transferred to help launch the new assembly line. At this writing, three of the six have remained in an assembly function. “They didn’t want to go back to machining,” Smith said. “They’re still on the assembly line.”

The Final Layer: Engagement

Smith made a confession. In 2008, when NSA managers (responding to requests from a few major customers) hired a person with a background in lean manufacturing and Six Sigma, Smith, like many others at NSA at the time, was against it. The concept of lean manufacturing wasn’t new to the company; managers had led lean projects in certain areas. But at the time, Smith and others thought that lean principles just weren’t broadly applicable.

NSA invested in solid-state laser cutting in 2012, becoming an early adopter of the technology in the region.

“I’ll be the first to admit it: I once thought we couldn’t do lean. I thought it just wouldn’t work here.” He then paused. “Change comes hard sometimes, even for me. I now confess, it’s made a tremendous difference.”

The day Smith said this, Darci Ruggles, NSA’s continuous improvement and quality director, was visiting a customer to discuss manufacturability attributes for a new part program. Before designs had been finalized, Ruggles gave her input on how to error-proof assembly, from the placement of holes to the size and shape of sheet metal parts.

This is how continuous improvement has progressed over the past nine years. Ruggles came from the automotive industry, but she knows what it’s like to work on the front lines too. At her previous employer, she started on the shop floor as a machine operator. From there she rose to become an area supervisor, then worked in quality and, finally, continuous improvement.

When she came to NSA in 2008, she began implementing Six Sigma Green Belt and lean training. She has since helped standardize work practices for setups, quality inspection, and production processes. She has helped improve kanban (part replenishment) arrangements with customers and implemented new kanban programs for repeat work.

Her role has expanded to the point where she helps engineers set up manufacturing cells. “In the past three years, we’ve really ramped up our assembly capability,” Ruggles said. “We’re setting up single-piece flow and error-proofing wherever we can.”

This has evolved to the point where Ruggles is now visiting customers before their part designs are finalized. “For one customer, we’re working directly with the firm that’s designing the product, and we’re developing the assembly process as they’re doing the design.” Ruggles conceded that this isn’t typical, but in many ways, it’s ideal.

As both Ruggles and Smith explained, offering these services may help the company turn more new customers into major customers in less time. This, combined with an acquisition strategy, may well lead to an even larger NSA Industries, with more metal manufacturing coming from the woods of northern Vermont.

Photos courtesy of NSA Industries.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI