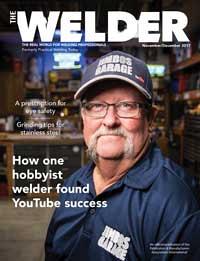

Owner, Brown Dog Welding

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

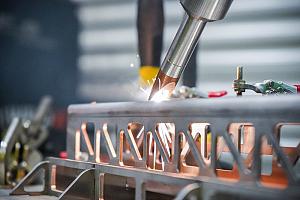

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

It’s never too late to pay attention to the details

- By Josh Welton

- November 11, 2017

- Article

- Arc Welding

Attention to detail. It’s separate from talent, experience, and skill, and even from work ethic. It’s a concept that can cover for a multitude of weaknesses, and yet it often gets glossed over or ignored completely in the early stages of a welder’s education.

In regards to focusing on “the little things,” I’ve often heard that fabricators either do it or they don’t. But in my opinion, it’s a practice that isn’t emphasized as much as it should be.

Thinking back to my early days as a millwright apprentice at Chrysler, I remember the first welding certifications I did. During that time two instances occurred that hammered home the importance of paying attention to the details, and they have stuck in my brain ever since. Neither has anything to do with technique or even skill (at least not completely). It was exorcising the demon living in the details.

The first learning moment came while doing a 3G open-root weld with a 7018 electrode. I was still struggling to see the puddle at this point, so there was some slag caught in the corners, because I didn’t hold the edges long enough. We weren’t allowed to use any type of power tool to clean, so I had a cold chisel, a pick, and a wire brush at my disposal to clean between passes. My instructor warned that it was imperative to remove all slag, saying even though it may look like I could burn it out with the next pass, in reality the bead would flow over the hard slag and leave an inclusion.

I ran my pass, chipped the slag, brushed the bead, and picked the corners. Being the impatient kid that I was, I cleaned out a majority of the junk stuck in the edges and felt it was good enough. Surely that tiny amount of slag would burn out. Once the groove was filled and the cover passes added, the plate passed its visual inspection. Then I sanded the welds flush and cut the 6- by 1½-in. coupons.

The hydraulic ram by the front wall of the weld shop was nicknamed “The Heartbreaker.” It earned the nickname because many a welder saw his or her dreams of clean bends crushed in an instant with no regard for their feelings. I was relatively confident as the destructive testing began. But welding is a humbling trade, and by taking an ill-advised shortcut while cleaning, I did indeed leave slag inclusions that showed up as the welds stretched.

That was the first and last time I failed a destructive test. I learned that what seemed like a little detail, in the form of a little speck of slag in the corner of a vertical pass, would ruin my day. No way was I letting that happen again. Every bead I run is cleaned, scrutinized, and cleaned some more. And, honestly, it doesn’t take much time once you get your system down, plus the payoffs are knowing the weld you just laid down is as strong as it could possibly be.

The second lesson I learned about detail is in regards to TIG welding, and it highlights the difference between doing something good enough and doing work that reaches the ceiling of your potential.

Between the guys I worked with at the Chrysler plant and the initial welding classes I took as an apprentice at Macomb Community College, I knew how to sharpen a tungsten electrode. At the Chrysler plant we had a dedicated tungsten grinding wheel, although it wasn’t the finest grit. Still, I knew to finish the angled point so any grinding marks were parallel with the tungsten; to leave a little land at the end for the arc to jump from; and how different tungsten profiles affect the puddle size, shape, and depth. Even with my limited experience and knowledge, I had the concept down.

I was working on some practice pieces while prepping for my first TIG certifications at the Chrysler/UAW Training Center. The beads were coming out decent, but the class instructor and CWI Fred Bernier showed me how a little more prep could take them to the next level. Fred took me over to the welding lab’s pedestal grinder—they had a fine-grit wheel for the tungsten prep; it wasn’t quite a diamond wheel, but close enough—and he sharpened my tungsten electrode with a skillful, light touch that left a nearly polished finish on the angled tip.

The difference between how the arc reacted before and after was slight but definitive. The arc was stronger, the puddle smoother and easier to manipulate. On everyday repair work or general fabrication, it’s doubtful that extra 1 percent would make a difference, but on a piece with more stringent requirements or in need of a delicate touch, the exacting electrode finish is a necessary detail for consistent success. This wasn’t about talent, hand-eye coordination, or “being the puddle”; it was again about focusing on a detail I once overlooked.

In MIG welding, the lack of attention to detail often manifests itself as a machine that “won’t run right.” I can’t count how many times I’ve heard a welder blame the machine for their poor performance. Guess what? I’d say that 99.9 percent of the time the cure is as simple as doing a little maintenance. Too many fabricators don’t perform the basic tasks required to keep a MIG setup functioning properly. Most often the root of their frustration and their poor welds is something small that requires a simple fix.

I could share so many examples about this, so here’s a fun one.

Every now and then I’m stationed at Fort Huachuca in Sierra Vista, Ariz., for my job at General Dynamics Land Systems, where I work in their prototype shop as a driver/mechanic. When I’m there, I like to visit Tombstone as it’s only about a 20-minute drive south of the base. I’m not gonna lie, I’m kind of a fanatic of the movie. I really dig walking through the O.K. Corral where the famous showdown between Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, and the outlaw cowboys took place. Currently there is a functioning blacksmith shop literally in the exact location of the shootout. How cool is that?

On one of my visits I got to talking to the man hammering on the anvil, a burly, bearded old-timer whose name is Grizz. He gave me a bit of his background and I did the same, and I told him how I’d always wanted to blacksmith. When you can have an informed conversation about metal, whether you’re a welder, fabricator, tin knocker, millwright, or blacksmith, I think there is a trust that forms. He mentioned that he had a little 110-V MIG welder that he used to stick together pieces of metal for souvenir trinkets, and that it had faded to the point where trying to use it was an exercise in futility. He figured that something was wrong with the machine, but his background wasn’t in welding, at least not in any type of modern welding.

I offered to look at it. I had a sneaking suspicion that a little attention would cure what was ailing the machine, and that it would be zapping tchotchke again in no time. Sure enough, the nozzle was filled with so much spatter that it was stopping the flow of gas. The contact tip also had spatter on it, which, along with the mess in the nozzle, caused the welding wire to either arc out and sputter or jam and birdnest. There weren’t any spare consumables, so with a pair of wire cutters, a file, and a steel brush, I did what I could to clean up what was there.

I put it back together, ran a couple of test beads, adjusted the tension of the rollers, and then handed the gun to Grizz and told him to give it a shot. He pulled the trigger and said it felt like a new machine. In exchange for my help he told me to come by again for a blacksmithing lesson or two. So, geeking out over Tombstone and my passion for metal collided and I experienced blacksmithing in the O.K. Corral!

Even the smallest, most seemingly insignificant things, like failing to clean or replace your consumables, can escalate to complete machine malfunction. Missing a little speck of slag between passes will leave an inclusion that could lead to a weld busting out. And a haphazardly prepped tungsten might have you wondering why your TIG puddle is all over the place.

It’s never too late to work on the small things, and they truly do translate to success in larger things as you progress in the trades. Attention to detail is not something that just happens. It’s a learned trait, and you’ll have it only if you put it into practice on day one.

About the Author

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Trending Articles

Aluminum MIG wires offer smooth feeding, reduced tangling

The role of flux in submerged arc welding performance

Three ESAB welding machines win Red Dot Awards for product design

Power source added to cobot welding system for simplified automation

Torch made for welding thin, conductive sheet metal

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,