- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Weld Olympics challenges students away from the booth

High school welding competition promotes hands-on learning

- By Amanda Carlson

- May 21, 2019

- Article

- Arc Welding

The Weld Olympics, a welding obstacle course competition, debuted 11 years ago in an effort to get student welders out of the booth and welding in creative and sometimes uncomfortable situations.

Oddly enough, the Weld Olympics, hosted by Yuba College in Marysville, Calif., and traditional Olympic events we have grown accustomed to over the years have a few similarities. It’s a fair statement as long as you are OK with replacing the balance beam with an I-beam; a half-pipe with a Schedule 40, 6-inch pipe; and dramatic torch-lighting ceremony with the striking of the oxyacetylene torch.

Dan Turner, professor of welding technologies at Yuba College, likes to say that welders are problems-solvers. Those aren’t empty words. It’s a principle he emphasizes in his classroom and one that he challenges himself to live by.

So it’s no surprise then that he employed this philosophy to creatively address a problem he and so many other welding instructors face—how to teach students how to weld outside the confines of a booth.

With the help of fellow instructors at community colleges and high schools in Northern California, along with material donation and mentorship from local industry, Turner helped usher in a competition called the Weld Olympics—a welding competition that gets student welders out of the booth and welding in creative and sometimes uncomfortable situations.

The Making of the Weld Olympics

In the field or in the shop, Turner is a big believer that welders need to learn how to be comfortable being uncomfortable. In 2008, about a year into his tenure at Yuba College, Turner, an energetic teacher with a passion for welding, wanted to build on the success he had as a high school instructor in Redding, Calif., where he held an annual event called Weld Camp. He discussed this desire with a friend and fellow welding instructor.

“I wanted to do a welding obstacle course, which is something I’d never heard of anyone else doing. The idea came to me about making an I-beam or pipes that students would have to crawl through and weld. And my friend said, ‘Well, why don’t we just have the Weld Olympics?’ It was an epiphany,” Turner explained.

The idea piqued Turner’s interest enough to fabricate an I-beam structure, name it Matilda, and teach his students the basics of structural welding. His students loved it, and so did he.

Other ideas followed. With help from organizations like Gerlinger Steel, Ironworkers Local 118, and Plumbers and Pipefitters 228, Turner began making more apparatuses for students to weld in or on. In 2008 the Weld Olympics made its debut.

The initial competition included high school and community college welders who participated in six events. But within the last three or four years, Turner scaled down the event to include only high schools.

“It’s really difficult for community colleges to coordinate time off and transportation. It’s also difficult to transport the various apparatuses that we had to a rotating venue,” Turner said.

One of the apparatuses at Yuba College’s Weld Olympics is the bunny slope, a plane on a 30-degree incline. Welders must complete a weld facing uphill and another facing downhill.

The competition, held every April at Yuba College, has two divisions: novice welders and advanced welders. Novice students complete weldments as a team, while advanced students compete independently.

Novice teams can include up to four people, with each person responsible for a weld or a cut on a weldment. The teams get to decide who does what. Advanced students must complete nine weldments and an optional 10th weldment for a tiebreaker scenario.

This year, 74 students from 10 high schools competed in the Weld Olympics.

Novice teams and advanced individuals had between 9 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. to complete all of the weldments. Those who did not complete all of the weldments were not eligible for judgment.“Some people think that’s a little harsh, but the rules state all or nothing. They have to prioritize their time and plan accordingly to complete all of their welds. It puts a lot of responsibility on the students.”

Drawing Inspiration From Real Life

Each event was designed to mimic something Turner has either seen in the field or in his imagination. There’s the bunny slope, which is an inclined plane at 30 degrees. Students must complete a weld facing uphill and downhill. Or there’s the cage, an apparatus inspired by the board game Mouse Trap.

“I was playing the game with my kids and the idea hit me when the little basket at the end came down and trapped the mouse. I thought it would be so cool to put a fixture in the middle of that and hang it from a chain. I went to school and built the cage. The only things that go in the cage are the students’ arms. They have to learn how to brace the cage to keep it from moving. It was received very well.”

Before the competition begins, Turner walks students through each apparatus to give them the real-life inspiration behind what they are about to do.

“I give them a real-world application to each event, whether it’s something in my past that I’ve done or something that I’ve seen someone else do out in the field. I want them to be able to understand why we’re having them do this and that it’s not us trying to be mean or make things unnecessarily difficult for them.”

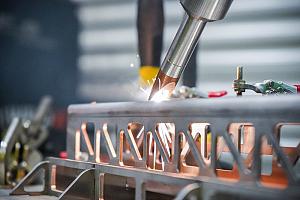

To keep things fresh, Turner imagines a new event every year. In this year’s new event, students took a Sch. 40, 6-in. pipe donated by Frank M. Booth Inc., Marysville, Calif., and cut it in half using an HMM pipe beveling machine. Then they flipped the pipe over and used portable engine drives to weld the pipes back together in the 2G position. Turner said the students absolutely loved it.

Students also weld on Matilda, the I-beam. Turner emphasizes the importance of welders becoming comfortable welding while uncomfortable.

Foothill High School, Palo Cedro, Calif., swept the top three spots in the advanced category, while Yuba County Career Academy, Marysville, Calif., won the novice division. Lincoln Electric donated prizes to the winners.

The Weld Olympics are a labor of love, not just for Turner, but also for his Yuba College students who help out, the college administrators, and the instructors of the participating schools who provide assistance during the event. It’s worth it for all involved because there’s a payoff that goes beyond placements and prizes that might not be immediately evident.

“It’s a work-world competition, not a booth-world competition. It forces students to look outside of their normal, everyday life. It allows students to explore and experience and build self-confidence when they accomplish something they never thought they could. When you have a chance to compete with and observe students from other schools, it gives you perspective on where you’re at in your own abilities,” Turner said.

Photos courtesy of Dan Turner, professor of welding technologies, Yuba College, Marysville, Calif., https://yc.ycced.edu.

About the Author

Amanda Carlson

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8260

Amanda Carlson was named as the editor for The WELDER in January 2017. She is responsible for coordinating and writing or editing all of the magazine’s editorial content. Before joining The WELDER, Amanda was a news editor for two years, coordinating and editing all product and industry news items for several publications and thefabricator.com.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,