Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A talk with Thermwood’s CEO, author of a new book on large-scale 3D printing

The founder of Thermwood Corp., Ken Susnjara, discusses building CNC routers and large-scale additive manufacturing machines that can be ordered with beds up to 15 x 40 ft.

- By Don Nelson

- November 15, 2021

- Article

- Additive Manufacturing

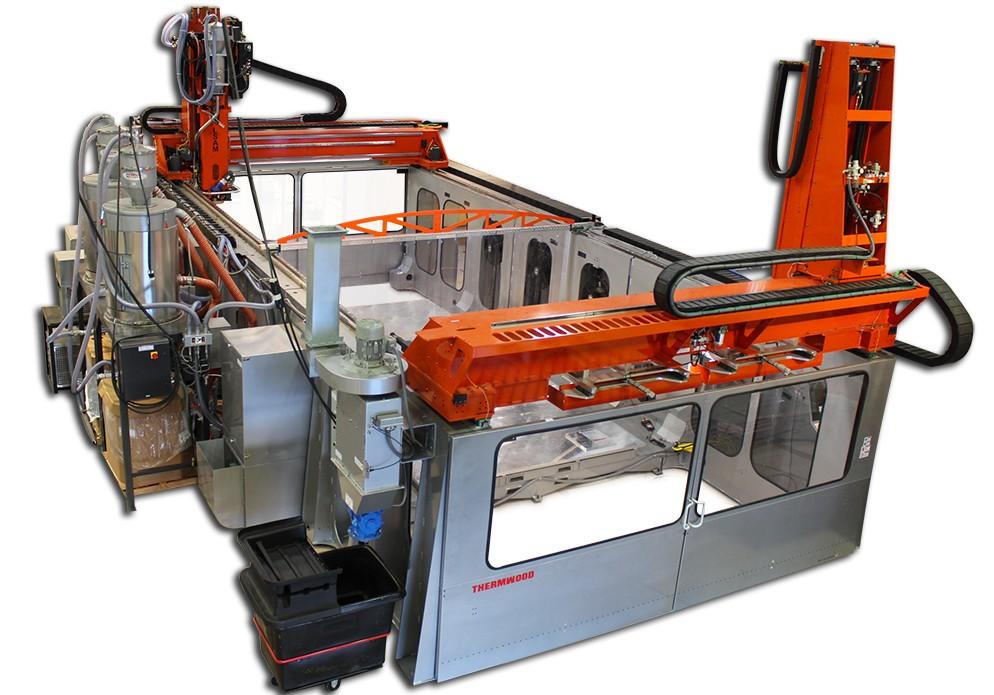

Ken Susnjara thinks big. He’s the founder, chairman, and CEO of Thermwood Corp., a machine tool builder that produces 3- and 5-axis routers and large-scale additive manufacturing (LSAM) systems with work tables measuring up to 15 x 40 ft.

(Here's a video of a helicopter blade mold being 3D-printed on an LSAM.)

Susnjara opened Thermwood more than 50 years ago, when he was in his early 20s, to mold plastic parts for the furniture industry. The Dale, Ind., company developed a thermoforming process that cut cycle times from around two minutes to less than five seconds using tools that were 90% cheaper than conventional tooling.

The Indiana facility processed millions of pounds of polymer materials annually. Thermwood designed and built much of the extrusion equipment used, which, Susnjara said, was highly automated and allowed the company to maintain a production labor cost of less than 4%.

Then came the oil embargo of the 1970s. It put the kibosh on imports of the oil needed to make polymers. Many of Thermwood’s customers abandoned plastic in favor of wood.

Thermwood looked for new opportunities and identified a need in certain industries for automated trimming of complex molded parts. Shortly after, it introduced the world’s first commercially available CNC routers.

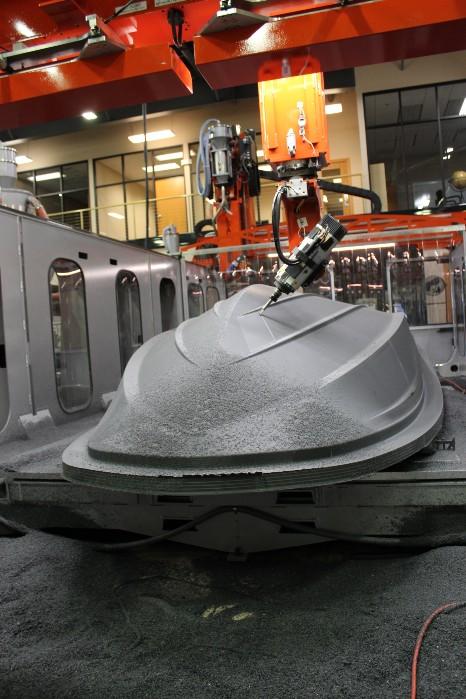

The following decades brought steady advancements in the routers’ hardware and software. Then, in 2016, Thermwood introduced the LSAM (pronounced “el-sam”). The combination machine 3D-prints and trims large composite parts, such as the tooling used to build molds for fiberglass boats.

Besides being an innovative entrepreneur, Susnjara is a prolific author. He’s written 10 books on topics that include the furniture industry, industrial robots, and, most recently, LSAMs. Titled A Manager’s Guide to Large Scale Additive Manufacturing: Understanding a New Technology, the book offers practical advice for manufacturers contemplating the use of large-scale 3D printing.

Don Nelson, editor of The Additive Report, interviewed Susnjara in October, shortly after the book’s publication. Following is an edited excerpt from their conversation about the company and Susnjara’s new book.

Additive Report:How did you come up with the idea of using a microprocessor on a router?

Ken Susnjara: After the oil embargo in the early 1970s cut off supplies of polymer, our customers panicked and stopped ordering plastic parts from us. We looked for things to do with our parts-making process, but everything we found required elaborate trimming. Trying to trim by hand wasn’t an option. The only machines out there were tape-fed NC routers. So we decided to build one too.

Around that time, though, I bought a calculator. The calculator was amazing. It could add, subtract, multiply, and divide, and it was only a thousand dollars.

I asked how it worked and was told it’s run by a microprocessor. Nobody knew what that was, so I got a book: a three-ring binder containing mimeographed sheets of paper that explained microprocesses. I read it several times but didn’t understand all of it. I called the author and asked for help.

He said, “Yeah, no problem.”

He offered to build a control in six to eight weeks for $10,000 to $12,000. Well, it took 18 months and cost a million-and-a-half dollars, but I had what turned out to be the very first commercially available CNC system in the world. We used it to create the very first CNC router. Eventually, we sold off the plastics business to focus on routers.

AR: What’s the story behind launching the LSAM line?

Susnjara: Someone named Byron Pipes, a composites expert from Purdue University, said he’d like to visit the plant. He brought a man with him who owned a company that made composite parts for aircraft. They introduced us to large-scale additive and told us that with our background and the things we knew, we would be ideal for that business.

One thing led to another and here we are. So it’s kind of Byron’s fault (laughs).

AR: What types of companies buy LSAMs?

Susnjara: Some of our first customers were very large aerospace companies, which is interesting. Large companies typically aren’t at the cutting edge of technology. They wait until the technology gets fully developed, documented, and proven, then they bring it into their operation.

Susnjara has written 10 books, including the latest about large-scale additive manufacturing. Thermwood

But they can’t do that with additive. The technology is so disruptive and has such potential to change the competitive nature of things that they have to jump in at the front end, which they’re totally uncomfortable with. Their systems are designed to not do that.

So, often, a large aerospace company will work with an entrepreneurial company and you get this clash of cultures. You could almost write a book on that.

AR: What are good applications for LSAMs?

Susnjara: Anything where you need a large outer surface: molds, vacuum fixtures, trim fixtures, plugs from which you pull molds for making fiberglass boats. We’ve done some work on large draw dies—huge tools used to pull an aluminum skin over a curved section of an aircraft.

Our machines were also used to 3D-print the 93-ft.-tall torch at Las Vegas Raiders Allegiant Stadium. We were involved with creating that thing almost from the beginning.

AR: You told me one reason you wrote the new book is because the market doesn’t understand large-scale additive. What don’t they understand?

Susnjara: Originally, people believed you could produce anything with 3D printing, and that you could do it quicker and cheaper. That’s not true. The process has capabilities and limitations. And once you understand them, there are certain products that you can make that will save you a ton of money.

AR: What are other reasons for writing the book?

Susnjara: To provide background on what additive materials are like. How the process works. What you have to do to make the process work. And if there are problems you’re going to have to deal with, I cover how we dealt with those problems.

I don’t want people jumping into LSAM and be missing some major point that could mess them up.

AR: Prospects sometimes send you test parts to print so they can evaluate the feasibility of purchasing an LSAM. You write that they often send their most complicated part, which is a bad idea. Why?

Susnjara: The danger when you send your most complex piece is that the process may not work for that piece. Then if you say, “The process won’t work for me,” you’re giving up all the savings you could have had on all the other products you could make with additive.

You’ve got to recognize that what you’re trying to do with the LSAM process is make money. There’s a possibility that what you make can be made at a lower price with additive. We’ve had some experiences where the material cost for a 3D-printed part was 45% less and labor was 70% less than with traditional ways. If you can get those kinds of savings for the majority of what you do, you ought to grab it.

AR: In one chapter you write about the lack of slicing software available for large-scale AM when you were developing your system. How did you solve that problem?

Susnjara: Over the years, we’ve written some fairly sophisticated artificial-intelligence software for making furniture, parts, and cabinets. However, we’ve also learned that once you put a software package on the market, you are going to live with it forever. So we decided we didn’t want to develop slicing software.

We talked with everyone who said they were in the slicing software business, and in the end, none of it worked. We ended up deciding we need to do this in-house, but we ought to find someone who is a little more experienced. We found some people who were part of a group that had written some major CAD/CAM software. They had created slicing software for other applications that were not polymer applications. We worked out a deal to buy the rights to that software and then began to adjust and modify it as we learned things.

It took a huge effort to get the software to work with our machine and with the way our process works.

AR: Part of the book’s title is “understanding a new technology.” AM has been around for more than 30 years. Is it really new technology?

Susnjara: Large-scale additive technology happening today wasn’t happening a year or two ago. The technology is pretty much brand new. I mean, we’ve got over 60 patents on the LSAM already. If it wasn’t new, that wouldn’t happen.

AR: There’s an interesting line about patents in the book. You write, “If it doesn’t move, paint it. If it does move, patent it.” What’s behind that saying?

Susnjara: We created some technologies used in the furniture industry that were adopted by the whole industry, and we got very little benefit out of them. So we learned some lessons about protecting ourselves when we come up with new ideas.

A Manager’s Guide to Large Scale Additive Manufacturing: Understanding a New Technology can be ordered at Amazon. Click here to view a video of the interview with Ken Susnjara.

About the Author

Don Nelson

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8248

About the Publication

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI