- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Additive training moves online

The coronavirus pandemic has forced much of 3D printing training to be done virtually

- By Holly B. Martin

- September 22, 2020

- Article

- Additive Manufacturing

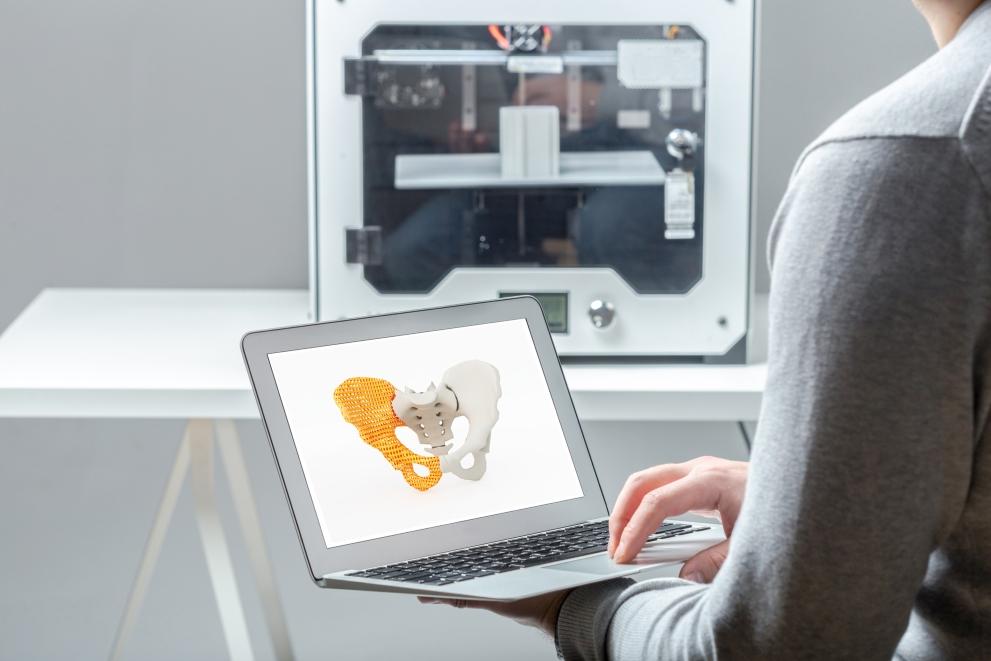

MIT’s xPRO AM course covers additive applications relating to aerospace, automotive, medical, and other parts. MIT

COVID-19 has changed the learning landscape, with many training providers switching to remote learning—at least temporarily. In the meantime, the need for skilled additive manufacturers/3D printer operators and engineers continues to climb as new technologies, software, and materials come on the market.

“There’s an important need for additive manufacturing courses at all levels of experience,” said John Hart, professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and head of the MIT xPRO Additive Manufacturing for Innovative Design and Production course. “We developed our course to fill what we saw as a knowledge gap in understanding the fundamentals and applications of the technology, (and) to help the industry develop new programs and new businesses based on AM.”

The 12-week xPRO course covers polymers, metals, and composites and other advanced materials. It also includes three weeks of content focused on design for AM and two weeks working on case studies to integrate practical knowledge learned from previous weeks. The online course takes about five hours of work per week and is tailored for individuals of all experience levels in a wide range of professions, from engineers to physicians to supply-chain managers.

On the one hand, said Hart, there’s no replacement for students working on their own 3D printers, testing out the concepts they learn. “But we’ve found high-quality videos can be quite effective to give a sense of what the technology really looks like, and the course also gives learners hands-on experience using CAD and generative design tools.”

ASME Targets Metal

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) also offers AM courses, with a focus on metal laser powder bed fusion printers. Before COVID-19, the courses were offered at different locations, but for the time being they are only available online.

“We decided to concentrate on offering training for 3D printing with metals because that’s where we see a lot of excitement and where the opportunities exist for manufacturing,” said Arin M. Ceglia, director of learning and development at ASME. “And it’s also where design is a critical element because metals introduce extra complexities, such as postprocessing.”

The goal of ASME’s four-course professional package is to provide engineers a foundational understanding of metal additive and instill the ability to apply that knowledge to their jobs. The first course is a self-study general introduction. The last three are hands-on design courses in which learners work with CAD files and topology optimization software, then submit their drawings to be critiqued.

The design courses lead learners through the processes of replicating a part using 3D printing design principles, followed by modifying an existing part, and finally building an optimized part from the ground up.

“Our 3D printing courses are all currently self-study, although in September 2020 we are planning to release at least one short course in a virtual classroom format that highlights five of the most common reasons metal 3D-printed builds fail,” said Ceglia.

In-Person Training

The GE Additive Academy, which is part of the company’s Customer Experience Center in Munich, Germany, offers in-person training courses to end users of its Arcam EBM (electron beam melting) and Concept Laser (direct metal laser melting) 3D printers.

GE requires a trainer be present for hands-on operator training to prevent damage to the machine and to ensure the safety of the operator, said René Schricker, technical trainer at the academy. “I always compare it to driving a car—you need to have a trainer present that steps in when you do something wrong.”

The printers are constructed so that “it is difficult to hurt yourself, and security doors and security switches prevent exposure to the laser,” he continued. “But when it comes to dealing with the powder, improper handling can affect your health and safety, so we train operators to properly use personal protective equipment, including how to choose the right PPE and how to put it on.”

Along with equipment training, GE Additive also offers both hands-on and online training for 3D printing software tools, though Schricker said customers typically prefer face-to-face training.

For operator training on a range of Stratasys, MakerBot, and Desktop Metal machines, AM solutions provider TriMech offers in-person instruction.

“If we are doing operator-based training, then obviously the equipment needs to be there so learners can do calibrations and see the results,” said Ricky Shannon, lead AM applications engineer at TriMech. “And when we’re doing a design for an additive manufacturing class, we want clients to bring parts that they’ve had problems with to the classroom so we can brainstorm different approaches to tackling their issues.”

TriMech, which is based in Glen Allen, Va., and has locations throughout the eastern and southern coastal regions, also offers both in-person and online training in the use of SOLIDWORKS and other CAD programs. The SOLIDWORKS side of the business was able to adapt quickly to online-only and continue offering training when COVID-19 started, said Shannon. “However, a lot of the on-site additive manufacturing training classes were backed up due to the lockdown, though we’re starting to get through that backlog now as some of the rules are loosening up and we’re able to have visitors on-site at some locations.

“Who knows where technology will take us to start delivering digital training?” Shannon added.

SIDEBAR

Sometimes training continues after students finish their courses

Finishing a 3D printing course doesn’t necessarily mean students are done being instructed.

At TriMech, Applications Engineer Ricky Shannon sends out short videos to his 3D printing clients that feature useful tech tips. “It may be just a postprocessing technique or a new way to polish parts,” said Shannon. “I’m trying to get that little snippet of information out there to help engage with our clients and show them that there’s more capability than they’re probably exercising with their machine.”

Arin M. Ceglia said ASME focuses on metal 3D printer training “because that’s where we see a lot of excitement and where the opportunities exist for manufacturing.” ASME

René Schricker, training developer at GE Additive Academy, recently implemented what he calls “microlearning cards.”

“We created small cards with a few sentences of text plus a photo or a QR code that learners can scan to get a 30-second video demonstrating how to properly perform a procedure,” he said. “The goal is to not overwhelm people with information.”

Schricker cited as an example the importance of correctly installing the rubber lip covering a 3D printer’s powder-spreader blade. “If you do it wrong, your part comes out badly,” he said. “The user manual takes 20 pages to describe this procedure, and, as a result, nobody was reading it and people were doing it wrong, so we came up with a learning card that just focuses on installing the part at the right height.”—H. Martin

About the Author

Holly B. Martin

About the Publication

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI