Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

3D scanning specialist recalls some of his favorite projects

FARO Technologies’ senior applications engineer has 3D-scanned everything from pumps to bomb bays

- By Don Nelson

- October 2, 2019

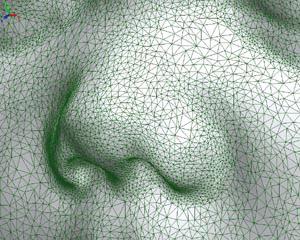

Les Baker worked on a project in England that involved scanning and 3D-printing the face of a blind mother’s infant son. Credit: 3D Scanners (UK) Ltd.

From sewage pumps to bomb bays to a representation of an infant’s face, FARO Technologies’ senior applications engineer and scanning arm specialist, Les Baker, has participated in a wide range of 3D scanning projects during his 20-plus-year career.

And, based on an interview The Additive Report conducted with Baker this summer at FARO’s Lake Mary, Fla., headquarters, he still marvels at the capabilities of the technology. “You can capture data for an entire midsize car in about half a day,” he said. “It’s that quick. Really, you could gather enough information to cause a Cray supercomputer to pause for breath.”

To lend perspective to how much data a 3D scanner collects, he said the company’s Laser Line Probes capture information at the rate of 300,000 data points per second.

He also said companies apply 3D scanners many ways. One FARO customer produces parts for large sewage pumps that originally were made by a manufacturer that went out of business long ago. “There are thousands and thousands and thousands of those pumps all over the world,” said Baker, noting that the patents on the pumps have all expired. When a pump part fails, it’s sent to FARO’s customer. That company 3D-scans the broken component—including any dings, flaws, and wear caused by years of use—then machines it.

“Once they’ve scanned the part and captured the geometry, they scale the replacement part to fit the pump as it exists today,” Baker said.

Early in his career, he 3D-scanned the bomb bay of a B-52 bomber to ensure that new weapons the aircraft would be deploying fit into the bay. More importantly, “they wanted to make sure the bombs left the bay at the appropriate time,” Baker noted dryly.

He also tells a story set in the early 2000s, when he worked at a scanning service bureau in England. A partially blind mother wanted a photograph by which to remember her infant son, but she needed something other than a regular 2D photo. The engineering department at a local university offered to 3D-print a polymer model of the child’s face. Baker scanned the baby’s face and prepared the datasets used to additively manufacture it.

“The mother wanted a 3D ‘photograph’ in order to remember the baby as he was,” said Baker. “Of course, the mother could touch the baby’s face at any time, but a photograph captures a specific moment in time.” That was what she wanted—“the opportunity to remember her baby’s face exactly as it was without the filter of memory to diminish it.”

About the Author

Don Nelson

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8248

About the Publication

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI