- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Hope dies last

Darrell “Big D” Hopper teaches welding, confidence, and the hope for a better tomorrow

- By Amanda Carlson

- July 9, 2014

- Article

- Arc Welding

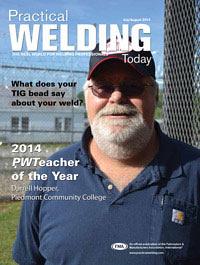

Darrell Hopper of Piedmont Community College, Roxboro, N.C., and the 2014 PWTeacher of the Year recipient, does more than teach students how to run a bead. He teaches them a craft and a way to put their signature on something that no one else can take credit for. Most important, he gives them a reason to have hope. Photos courtesy of Amanda Carlson, associate editor.

The name “Big D” is famous within the North Carolina penal system, not because it is attached to a notorious gangster or someone who has committed a crime, but because it belongs to a man who holds the keys to a gateway of opportunity, a new life, and a method for a man to provide for himself and his family. “Big D” teaches men a craft that no one can take away—a way for a man to put his signature on something important.

The inmates housed in Caswell Correctional Center in Blanch, N.C., a community of brick buildings shrouded heavily by thick trees and high, barbed-wire fences, know this. In fact, they clamor for a chance to learn from him. While those in other correctional facilities across the state don’t know what the nickname “Big D” stands for, they too know of the opportunities that learning from him can provide, and do everything in their power to transfer to Caswell Correctional Center just for the chance to take his class.

In essence, “Big D” is synonymous with one word: hope.

Giving Credit Where Credit Is Due

It’s not difficult to comprehend how Darrell “Big D” Hopper got his nickname. He stands roughly 6 foot 3 inches with shoulders as broad as he is tall. He is broad in the metaphorical sense too. For 18 years he’s made it his mission to educate Caswell inmates in the art of welding and fabrication. For many instructors, the task would demand too much. Perceptions, preconceived notions, and judgments might make it difficult for an average person to view the individual instead of the crime. But not Hopper. When he was hired as welding instructor by Piedmont Community College, Roxboro and Yanceyville, N.C., 18 years ago, he had a choice: Teach welding at the community college or teach welding to inmates at Caswell through the college’s corrections education program. For most, the choice is a no-brainer. The same was true for Hopper.

He chose the inmates.

To understand why, you must first understand Hopper. The jobs he worked before becoming a weld instructor always left him feeling disappointed. No matter how conscientious or thorough he was, and no matter how many potential disasters he helped diffuse, someone else always ended up receiving the credit for a job well done—a shift supervisor or a manager, for example—credit he felt like he deserved.

Hopper went out in search of a career that would allow him to put his stamp on things and where no one else but him would get the credit. That career, a friend told him, was welding.

“I didn’t know the first thing about welding. My nephew was going to Guilford Technical Community College in Jamestown, N.C., at the time, so I asked him to introduce me to the welding instructor there because I had decided to do it. I went right in and introduced myself—his name was Ken Kurt and he became like a second father to me. I told him that I wanted to be the best welder he ever had, and he just laughed at me,” Hopper explained.

The desire to become the best welder wasn’t easily accomplished. At 26 years old, Hopper had a wife and bills to pay. He couldn’t afford to quit working altogether in lieu of going to school full time, so to make ends meet he worked third shift as a production supervisor at a chemical company. He’d finish his shift around 3 a.m., drive to school, and sleep in the parking lot until class started. His alarm clock, he said, was a train that came through daily at 5:45 a.m. When he heard the train whistle, he knew it was time to wake up.

That, in a nutshell, was Hopper’s life for 2½ years until he graduated. Eat, sleep (in a car), work, and weld.

Darrell “Big D” Hopper stands alongside his 18 student welders and three teacher’s aides. Most had never welded until they started Hopper’s class last August, and now 14 are certified in all-position SMAW and GMAW.

“The day I graduated, my instructor shook my hand and told me that I had accomplished exactly what I said I was going to. So I’m thankful for it. He really pushed me, and that’s why I now push my own students so hard. He’d always tell us, ‘You can’t learn if you don’t burn,’ and that’s what my saying is too.”

Welding was everything Hopper thought it would be, and more. But after suffering an injury on the job, he began looking into teaching opportunities. After spending some time teaching welding to high school and community college students, the opportunity to teach inmates at Caswell Correctional Center presented itself.

To him, it sounded perfect.

Breaking the Recidivism Cycle

The rate of recidivism—a term that describes a person who reoffends and is sent back to prison—in the U.S. is staggering. In 2005 the Bureau of Justice Statistics tracked over 400,000 prisoners in 30 states and found that within three years of release, 67 percent of them had been rearrested. Within five years of release, 76 percent—three-quarters—were rearrested. And of those arrested, a little more than half of them—56.6 percent—were arrested by the end of the first year.

Those are sobering numbers that prompt two questions. The first and probably the most difficult to answer: Why? The reason varies from one individual to the next, but essentially, said Pat Ray, program director at Caswell Correctional Center, people reoffend because many times they return to the same environment, the same life pattern, and the same behaviors that prompted them to be incarcerated in the first place. Sometimes prison offers a better environment than anything they’ve got waiting for them on the outside.

“A guy I talked to had 352 days of disciplinary time he had lost, which meant he would have been out of prison 350-some days ago. I said, ‘Look what you’re doing! You’re keeping yourself in prison by getting in trouble all the time.’ And he just laughed. I asked him what was so funny and he said, ‘I ain’t got nowhere to go,’” Ray explained.

Oftentimes they enter prison with very little education, work experience, or hirable skills. Without those tools, they don’t know any other ways to make a living, so to speak, other than to fall into the same pattern they were in at the time of their arrest.

“I remember asking an inmate if he was excited about going home,” Ray continued. “He said, ‘No, I’ll just go back to doing the same thing I was doing.’ I asked him what he was doing, and he told me he was selling drugs. When I asked why, he said it was because his mom and dad told him to. His parents had him selling drugs so they wouldn’t have to. He was a youthful offender and if he got caught, he wouldn’t get as much time as they would. They even kept him out of school because they had this plan for him.”

The second question that comes to mind regarding this nation’s high recidivism rate: What are we doing about it?

The consensus there is the need for education, and here’s why. A study conducted by the Office of Research & Planning titled “Educational Attainment of Inmates Entering North Carolina’s Prisons July 2005” revealed that the average person who entered North Carolina Division of Prisons (NCDOP) read at a ninth-grade level and solved math problems at a seventh-grade level. A little more than half (52.6 percent) of inmates who entered prison in North Carolina in 2004 claimed they earned a high school diploma or successfully completed their GED® testing.

Motivational phrases and “Big D’isms” can be found scrawled on walls in soapstone inside the welding booths. Things like “Obstacles were made to be destroyed,” “Tighten Up,” and “Travel Speed, Angle, and Arc Length” serve as written reminders to the welders.

There is no better way to give inmates a leg to stand on once they are released than through education, Ray said.

In the case of Caswell Correctional Center, Piedmont Community College offers vocational training in the form of welding; heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC); industrial maintenance technology; and horticulture. Inmates who possess less than a high school education (or equivalent) have the opportunity to participate in GED preparatory classes or remedial education.

A study conducted by the RAND Corporation and sponsored by the Bureau of Justice Assistance found that inmates who participate in some form of corrections education are 43 percent less likely to return to prison once they are released. Employment upon release was 13 percent higher among those who participated in academic or vocational training than those who didn’t.

There is a potential for more harm to be done by not investing in corrections education. For starters, there’s the cost of housing an inmate. According to the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, in 2013 it cost $79.26 a day, or $28,929 a year, to house an inmate in a medium-security facility such as the Caswell Correctional Center. Costs are higher or lower depending on the level of security.

Researchers who conducted the RAND study found that a $1 investment in prison education reduced incarceration costs by $4 to $5 during the first three years after a person is released. Why? Because the ones who are participating in these programs aren’t going back to prison.

However, there are the naysayers—that is, the people who believe it is wasteful to spend tax dollars on corrections education even if statistics and studies reveal otherwise. To those people, Ray says to be careful what you wish for.

“A lot of people want to cry and complain about prisons having weight racks, game boards, televisions, and, yes, educational programs. Well guess what? If we didn’t have any of that, especially education, then those guys would be out there fighting all day long. If these guys have a skill when they leave, it means the general population won’t have to continue paying for these guys to live, be educated, eat, and sleep. It costs a lot of money to run a prison, and when you get somebody that’s not coming back, then that’s good for you.”

Mike Wall, correctional case manager at Caswell Correctional Center, agrees.

“If you don’t want to put the money or the time into teaching these guys to make better choices, then they’re going back to the streets and committing crime again once they’re released. We want to get them out in society and to have some way they can support themselves. And why not? We’re having to pay for their way in here,” Wall said.

Tough Love

Each August a new crop of 18 inmates walk through the doors of Hopper’s relatively small welding shop and transform into college students. Isaac Rogers, correctional programs supervisor for the correctional center, oversees all of the vocational programs at the prison and assembles the roster of inmates who will be the next to learn from Hopper. Sometimes that includes an inmate who has specifically requested a transfer from another facility just to take the welding class.

Hopper teaches his students that the best-paying jobs are in structural and pipe welding, so class time has a heavy emphasis on structural SMAW and GMAW in all positions.

“I get phone calls, e-mails, and letters from inmates and case managers from all across the state. The class that will be starting this August has been full since last December. It doesn’t take long,” Rogers asserted.

Some spend months on a wait list. Others spend months undergoing the transfer process only to be put on a wait list once they get to Caswell. Rogers said there are other very good welding programs within the NCDOP, but Hopper’s seems to be the most sought after.

Inmates know even before they begin the class that Hopper is tough. Rogers warns them. Former students warn them. But they don’t really understand what that means until they experience it for themselves.

Hopper demands that inmates leave their baggage at the door. They are on his time, and as such they are expected to work hard and keep an open mind. He’s not going to feel sorry for them. He’s not going to listen to their whining or complaining. He’s not going to show pity for their circumstances or, most importantly, judge them for what they’ve done in the past. His time is to be used for one thing: welding.

“I don’t want to know what their crime is. I don’t want to know what they did to get in here. I can’t deal with that. I want to look at everyone as equals. When you come through that door, you are a student of Piedmont Community College and I am your instructor.”

Some guys walk in with a chip on their shoulders. Some guys walk in hoping to test the famous “Big D.” Others have never experienced a structured environment outside the prison walls and don’t know what to do or how to act. Because of this, Hopper has to set clear boundaries right from the start—like the importance of being on time, respecting equipment, hard work, and good behavior both during class and during off days. He has a zero-tolerance policy for disrespect. For most guys, the first few months are hell, but Hopper is very honest with them in that regard. He tells them flat out that they aren’t going to like him very much in the beginning. He makes no apologies for being tough because he knows that the rewards for those willing to stick it out and learn are endless. Co-workers at the prison like Wall and Ray understand and appreciate it as well.

“He teaches them tough love. He’s tough on the inmates, but he’s giving it to them the way the streets will when they get out. They walk a tight line under him, and if they veer off that line, he’s real quick to kick them out or teach them a life lesson,” Wall said.

Added Ray, “Darrell comes off as very strong-willed and hard-core. He’ll yell at them in a skinny minute, but they read that into being honest and that he means well by it.”

There are some like Joshua Proby, who walk in with their guard up and on high alert. Even though Proby is one of the many inmates who transferred into Caswell specifically to take Hopper’s class, trusting someone, even if they come highly recommended, is difficult.

“It’s hard to restructure a mind that’s already been set in something for so long. Your perception of an individual is automatically a certain way based on what you’ve experienced in your past. He obviously sensed that because within the first couple of days he said to me, ‘You need to get that chip off your shoulder,’” Proby asserted.

Space and equipment are tight, so two people share a booth. Hopper likes this system because he feels it promotes learning and healthy competition among the welders.

From 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. four days a week, Hopper tells them they are community college students, and will be treated as such. He teaches things the hard way, partially out of necessity, but also because he believes it’s the best way.

For example, there are no auto-darkening helmets. Only Hopper and his three teacher’s aides (also inmates) get the privilege of using those. Everyone else uses the old- school masks with the small view finder. Each welder also gets one pair of gloves for the year. Shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) electrodes are a premium inside those four walls, so each welder uses his electrode until it is only 2 inches long. Anyone who throws away a rod longer than 2 in. must fish it out from the scrap bin and get back to work.

Students start out learning SMAW in the vertical-up position. Most instructors begin by teaching the horizontal position, but not Hopper. He doesn’t believe in easing into anything—he’s a jump-in-feet-first-in-the-deep-end kind of guy. He also makes his students learn on the most difficult of SMAW electrodes only, either 6010 or 6013.

He emphasizes what he calls the five essentials—amperage, arc length, angle, travel speed, and polarity. He hammers those essentials into the brains of his students, teaching them the characteristics of each and how to identify when one of them isn’t quite right in their welds.

There are no grades; everything is either pass or fail. Welders move at their own pace, starting with overhead SMAW and moving through each position, and then switching gears to overhead gas metal arc welding (GMAW) followed by the other positions.

Due to budget constraints, there isn’t much room to add a full-fledged gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) or flux-cored arc welding (FCAW) section, but they are able to touch on it, albeit slightly.Students have the opportunity to certify in SMAW and GMAW. Hopper is a certified welding inspector (CWI), so when it comes time for guys to test, he transforms from “Big D” the teacher to Darrell Hopper the inspector.

“My emphasis is getting them certified. I want to get them a foot in the door when they get out. Even if the certification expires while they are still here, at least it tells an employer that they’ve been able to pass the certification test before. And it gives them the confidence that they can do it again,” Hopper said.

Once guys start passing certification tests or mastering various weld positions, they begin hating him a little less. Hopper asserts it’s because the guys are building confidence because they are seeing results. On top of the welding, Hopper assigns textbook work and requires his students to write him letters detailing their personal goals, expectations, and assessment of the class.

“They get homework. The first reason for that is they have to know their stuff. The second reason is it keeps them in the dorm, off the yard, and out of trouble. If they get in trouble, they’re done. I don’t let them back in.”

This year 14 of the 18 students earned double certification in all-position SMAW and GMAW and three earned certification in one of the two.

It’s Got to Be the Teacher

At the time of this writing, the 11-month class is coming to a close. Excitement is in the air because graduation is right around the corner—the prison and the college host a graduation ceremony, complete with caps and gowns, to honor the accomplishments of everyone who participated in educational or vocational training during the year. Everyone is still abuzz in the wake of the second annual Weld-off competition, in which a champion, second-place, and third-place finishers were crowned.

But the enthusiasm is tempered, both on the students’ and Hopper’s end. Graduation signifies the end of the road for this class and marks the beginning for a new crop of welders come August. Guys are going to have to find something else to occupy their time while they wait to be released. In some cases, the certifications they’ve earned will lapse and the momentum they’ve built during the nine-month class will go cold.

For some, those eight hours of welding time provide more than just an opportunity to learn a craft. They provide an escape, albeit brief, from the reality of their situations. Sometimes it can provide motivation to pursue their GED or higher education.

James Washington said the welding class doesn’t exactly make him forget altogether where he is or why he’s there, but it is a positive outlet that allows him to spend his time productively, doing something that will benefit him upon his release.“I’m not going to say it makes you forget, because you always know. But it is a release. When I’m on the yard, I feel stagnant. I’m wasting time. But when I come up here, I’m accomplishing something. In here I don’t have to look up and pay attention to the razor wire. I don’t have to look over and see that there’s a uniform standing and waiting to see how I’m going to react to something,” Washington said.

Even though Hopper is tough on them and expects more of them than what they even believe they are capable of initially, spending nine months with Hopper has taught them how good it can feel to master something that a man can call his own, something that a man can do to earn a good living and support himself and his family. Something that no one else can take credit for.

But most importantly, they’ve been given the opportunity to learn from an individual who has a genuine interest in them as welders and as people.

Some, like former student and current teacher’s aide Wallace Woodard, have gained a mentor and a friend. Woodard doesn’t get much mail or many visitors, but his time spent in the welding shop with Hopper, first as a student and now as an assistant, has meant the world to him.

“I guess this is why I see Darrell Hopper as my friend. He knows that I am alone so he has gone above and beyond his duty to teach me a trade so that I can make it once I’m out,” Woodard said.

On the flip side, the students mean the world to Hopper. He rarely has a conversation about his job that doesn’t start or end with him expressing how much he loves what he does and who he teaches.

I love my students. I want them to succeed at welding and to do more than I ever did,” Hopper added.

They are his kids, his works in progress, and his legacy.

In Their Words

“They made a serious mistake at one point in time. And that one point in time might have been all of five seconds, but it did cause significant injury or even death to somebody else. They made a bad decision, but we’re about giving them skills and changing the thought process that maybe led to that bad decision.”—Dr. Doris Carver, Piedmont Community College, interim vice president, instruction and student development

“As welders, he wants us to be the absolute best. As men, he does all he can to make sure we successfully and responsibly re-enter society. Where others see castoffs, ‘Big D’ sees potential success stories.”—Dan Boone, student

“They’re still people. They’re still here. And there’s still hope if somebody gives them something they can do that’s positive so they won’t jump back into their old ways.”—Pat Ray, program director, Caswell Correctional Center

“So many people have counted me out for the things that I have done. I’ve made mistakes all my life, but coming into this class gave me an opportunity to be good at something.”—Joshua Proby, student

“Now, I smile a little more. Before I didn’t even want to look at him and smile. That meant a lot. Not only did I learn to weld, I learned to become more outgoing. I appreciate the laughs and the opportunity to learn. You don’t get that every day here.”—James Washington, student

“I’ll see them on the yard after the first week and they’ll tell me how tough he is. But at the end of the year at graduation, they go up and hug him. Most times you don’t see grown men hug, but they go up there and grab him.”—Isaac Rogers, correctional programs supervisor, Caswell Correctional Center

About the Author

Amanda Carlson

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8260

Amanda Carlson was named as the editor for The WELDER in January 2017. She is responsible for coordinating and writing or editing all of the magazine’s editorial content. Before joining The WELDER, Amanda was a news editor for two years, coordinating and editing all product and industry news items for several publications and thefabricator.com.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI