Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

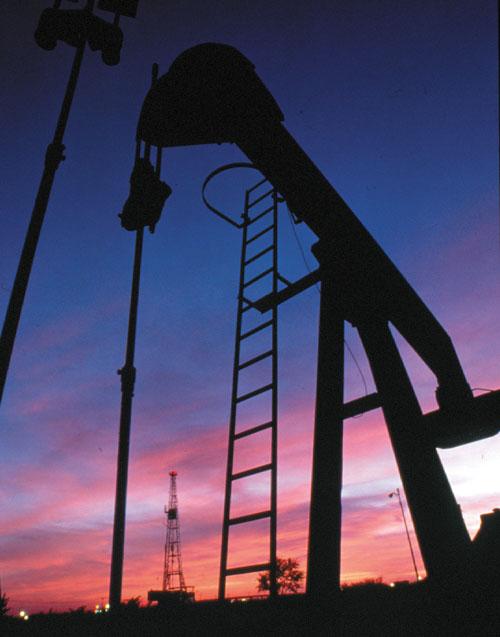

Odessa, oil, and the welding arc

Oil prices may be dropping, but for now the demand for welders isn’t

- By Tim Heston

- February 19, 2015

- Article

- Arc Welding

In late December investors sounded the alarm bells. The oil glut was upon us, they said. Saudi Arabia was keeping the taps open, and the rush to produce more and more shale oil continued unabated. What does the future hold? By press time in early January, some oilfield companies were announcing layoffs as oil plunged to less than $50 a barrel. The Dow plunged briefly, not so much because cheap oil is bad for the economy—for most parts of the consumer-driven U.S., it’s not—but because of uncertainty.

In his January Fabrinomics® e-newsletter, Chris Kuehl, economic analyst at the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International, put it this way: “The U.S. has been relying on the energy sector for the bulk of its growth the last few years, and losing that sector momentum will hurt. The good news is that the U.S. has other sectors that are benefiting from the low price, which offsets the loss from the energy sector—for now. Long term, the U.S. has as much interest in seeing oil prices climb as do the nations of OPEC, but there is no enthusiasm for oil prices much past the $100 a barrel level.”

The people on the ground, the fabricators and welders at the heart of the boom, seem less worried about a bust, and more worried about traffic and housing. James Mosman, associate professor of welding technology at Odessa College in Odessa, at the heart of the west Texas shale frenzy, put it this way: “We’re right dead in the middle of oil and gas country here in Odessa, in the middle of the Permian Basin. It’s slowing down a little, but not by much.”

This Time May Be Different

West Texas boasts some of the country’s lowest unemployment rates. In September Odessa’s unemployment rate fell to 3 percent; neighboring Midland’s was at 2.6 percent. In a boom and bust market like oil, a lot can change in a hurry. But according to some who have lived in west Texas through many booms and busts, this time seems different. For one, the boom is longer. The uptick in Odessa started more than five years ago, while the real boom began within the past three years. According to the Odessa Chamber of Commerce, sales tax revenue has increased for 56 consecutive months.

Michael George, CEO and chairman of the Odessa Chamber, explained that technology in oil exploration has changed the game. “It’s different from years ago, when they didn’t have the technology to tell them where the oil was. They did a lot of wildcatting. People were drilling, and a good percentage of these wells ended up being dry holes, and people would lose their investment.”

Today, technology has reduced the risk of finding only dry holes. “Because of technology, they now know where the oil is, and they know how to get it out of the ground, out of the tight rock formations, because of the hydraulic fracturing,” George said. “The price of oil now dictates the rates of return. That’s different from years ago, when the oil price had to be so high to offset the risk of investment.”

He added that all this has drawn to Odessa hundreds of service companies that focus on specific areas of technology that help develop the oilfields. So when an oil well is drilled, myriad companies are involved. “This has spread the wealth throughout the community throughout hundreds of businesses.”

Playing Catch-up

Investors of course care about the rate of return, and a lower return may mean less investment. The area may experience a slowdown in 2015, but according to fabricators who have a front-row seat in the boom—welding educators, company owners, weld inspectors—a moderate slowdown in 2015 wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world.

“We know there will be a slowdown,” George said, who added that Odessa’s economy has diversified over the past two decades into health care, distribution, education, and other sectors. “We no longer have our wagon hooked to just one horse. But we see [a potential slowdown] as an opportunity to develop more infrastructure for when the price of oil rises again.”

“You have the doomsayers, those who say the end of the boom is near,” Mosman said. “It may be slowing down a little, but that would be a good thing. It would give the industry some time to catch up.”

Almost two dozen hotels have been built in and around Odessa within the past three years. Traffic is a bear. Housing is being built as fast as possible—6,000 living units, including houses and apartments—in the past three years. “And all that isn’t enough,” George said. “Many of these oil service companies have living trailers in their yards, where they’re housing employees who they’ve recruited from other areas.” RV parks are full of workers from out of town, and the local industry still doesn’t have enough people to fill all the available jobs.

“If you try to go out and eat, or go to the grocery store, it’s crowded everywhere,” said Tim McCallum, a lifelong Odessa resident who works in nondestructive examination. “Many suspect this oil price drop will last six to nine months, but that’s not really a long time in the scheme of things. [As of December], work hasn’t slowed down.”

For welding in particular, demand for qualified workers has far outweighed supply. This has created a new Wild West of sorts, and welders have become the modern-day cowboy, the mortar holding the infrastructure of the oil boom together. Without the welding arc, no oil flows.

During his morning commute to Odessa College, Mosman passes dozens of welding trucks, all on their way to the drilling rigs, derricks, and pipelines. Hydraulic fracturing is happening everywhere, including, literally, in his backyard. Within the past two years, he said, more than 100 drill sites have been installed within 10 miles of his house.

“There are more welders here per capita than anyplace else I’ve ever seen,” he said. More than 15 years ago, he typically had between 50 and 60 welding students. “In the fall I had more than 230 students,” he said, “and more than half of them are working full-time and going to school at night to improve their skills.”

Scott Parker, vice president of sales for International Derrick Service, has lived in Odessa since 2003. “Back then, when I drove to work, I saw the same 15 to 20 welders driving on the highway, and I would know all of them. Now I might see 100 different welders, and I often don’t know any of them.” His company contracts with various welders, depending on the job; a minor rig repair might require only a few, while a complete overhaul might require 70 or more.

Two Kinds of Welders

Over the years Mosman has trained two types of people: those destined for the shop to weld pipe and other pieces of large equipment used in the field, much of it ASME Section IX work, and those destined to become the independent contractor for rig and pipeline welding. These contractors may work 14 days with only one day off and be on 24-hour call. “They’re out there chasing the oilfield, performing the pipeline work,” Mosman said, and they’re often welding to API (American Petroleum Institute) standards.

“The guys are doing exceptionally well,” Mosman added. “There’s more work than they can handle. Still, some people don’t like to constantly chase the job. So they’re happy in big fabrication facilities building products for the oilfield.”

Demand for combo welders, those who can do gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW, or TIG) root and shielded metal arc welding (SMAW, or stick) cover passes, are on the rise, too, especially for welding the 316 stainless pipe in the field processing plants that separate the crude oil and the fuel gas from hydrogen sulfide, or “sour” gas.

Many start young in the field and then settle down as a shop welder to raise a family. Some start in a facility but then see greener grass (with better pay) in the oilfield. They jump out into the field, then realize that it isn’t the life they want, so they return to the plant.

(Source: Getty Images)

“There are more welders here

[in Odessa, Texas] per capita than anyplace else I’ve ever seen.”

—

James Mosman, Odessa College

“It takes a tough person to be out in the weather, from freezing cold to our Texas summers, where we were hitting 110 with the wind blowing. It’s like being in a blast furnace,” Mosman said. “And in my opinion, you need a little bit of swagger to do it. They’re the modern-day cowboys. They have their gear and they’re out there chasing the job.”

In oilfield work, connections mean everything. As Mosman explained, a welder’s reputation, good or bad, gets around. For these welders, personal connections and networking land the jobs—and with enough jobs, a $200,000 gross income isn’t out of the question.

“Of course, when you take off everything they have to expense, they’re still doing OK, but they’re not taking home that much. To work on some of these oil rigs on location, these guys need $2 million to $3 million liability insurance in some cases. They need a new truck every few years, a new welding machine. If they’re good businesspeople, they’ll do very well. You need that entrepreneurial spirit.”

Mosman said he’s also seeing more self-shielded flux-cored welding in the field, but stick welding, using the 6010 or 7018 electrode, is the perennial standby. “I do CWI work, and most of the API testing I do is still 5P+ downhill, or 7010 downhill, welding on the big 12-inch pipe. Two summers ago I tested more than 100 pipeline welders from all over the country, and they’re here working the oilfields.” He added that welding automation has crept into Odessa, particularly for in-plant work, but it’s been a slow creep. Manual welding still rules in the Permian Basin, Mosman said, and it probably will continue to rule in the near future.

Whichever career track they take, welders are doing well, he said. The take-home pay for rig and pipeline work may be more, but so are the insurance premiums and all the expenses that come with being a sole proprietor. Meanwhile, in-plant welders have enjoyed the steady demand for parts and equipment to support the energy boom. All in all, despite future uncertainties, it’s not a bad time to be a welder in Odessa.

Demand Versus Talent

It’s not a bad time to be a business owner and manager either, but it’s also challenging when it comes to finding talent and scheduling. “I would say scheduling everything remains our biggest challenge,” Parker said. “For all our projects, we need to schedule [contract] employment, schedule the material for the job, and then finally schedule the job. When it’s booming, it’s difficult to find materials; we need to wait for the mills. Then that makes it hard to schedule a job, to get it delivered on a specific date.”

Like in any situation where you have immense demand and not enough supply, finding employees hasn’t been easy. “The sad thing is, I’ve heard some companies say, ‘Well, if I can get four days of good work out of [these welders], I’m happy,’” Mosman said. “With the demand as high as it is, unfortunately, that’s the way it is. When I was rising through the ranks, if you didn’t show up, you were out of a job, and they’d find somebody else. Now, it’s the other way around. The companies need people, and there aren’t enough people out there.”

McCallum, who manages people who examine welds every day, has noticed a downtick in weld quality. “The quality of welder is down from what we’re used to seeing. Typically, managers at these big pipeline jobs want their repair rate to be at 1 percent or less. And now it’s up to around 10 percent or more. That’s a huge difference in quality. It used to be that if you had three repairs, you were kicked off the job. Nowadays, because the industry needs them so badly, that’s not the case. They have more second chances now.”

He works at a facility that performs welder qualification testing, and roughly 60 percent of the welders he’s tested come from out of town. “I’ve seen a lot of people struggle with the testing. Out of about a group of 10, about four of them just don’t make it.” Again, he said it boils down to simple supply and demand: too many jobs, not enough talent. “The experience level is down because of the sheer volume of work that’s out there.”

Mosman is working with one ambitious student who’s in the lab every chance he gets, welding pipe. He wants to break out in the spring. He’s the first in the booth and the last one out. As Mosman sees it, no matter what the price of oil does in the coming weeks and months, those kinds of welders—those who put in the work—are sure to do well.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI