Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Making lean manufacturing work in a job shop

Thinking that lean principles don't apply to assembly in a job shop is wrong

- By Dan Davis

- May 7, 2015

- Article

- Assembly and Joining

Too many metal fabricators believe lean manufacturing principles don’t apply to them. They don’t have a regular product lineup, so they don’t have to worry about spending hours analyzing a production process. The job mix changes every day, and so do the challenges of any final assembly that’s necessary.

Ray Mikulak, a lean manufacturing authority and leader in online training for companies, believes job shops should reconsider that thinking. His company, Resource Engineering Inc., has offered lean guidance to manufacturers for years, but it is just now putting together courseware for shops with low-volume and high-mix jobs.

Early in his career he offered more consulting services to companies, but today most of the outreach occurs through online training. Over the years he has observed that some classic elements of lean manufacturing work well and others don’t. The FABRICATOR recently interviewed Mikulak to find out some ways that fabricators can streamline their assembly operations.

The FABRICATOR: What is the first thing a metal fabrication company should do when it is looking to introduce lean manufacturing into its assembly area?

Ray Mikulak: The first thing we would do, when we were consulting, was to have someone take us around, as if we’re an order. Let’s just walk through it the way the flow really is. And just by doing that, it opens up people’s eyes and they realize, “Oh my God, I’m just walking back and forth all over the place.”

That is a good way to get people to open up. Don’t skip anything. Walk exactly the way it goes. Of course, you may have to get the next person in line in the process to tell you what really happened, because the one that’s doing the processing will tell you the way it should happen, but may not be exactly what they do.

In a manufacturing facility, you just take a layout and plot out the flow. Then you ask the question, “What can we do to have less waste of transportation and movement?” and connect the processes together.

When it’s a high-mix, low-volume environment, it’s really complex because you are using the same equipment for so many things. But then it’s a matter of putting processes together, constructing a matrix, and asking, “What processes use what?” You end up identifying maybe four or five different families. No one uses everything the same, but we have a lot of similarities. Let’s focus on those, especially the ones that come up often and that are relatively high on the high-mix side. Let’s focus on those, put those processes together, and see how we can get them closer together. Let’s get the people talking to each other and eliminate some of the wasted motion.

FAB: What’s the best way to identify those product families?

Mikulak: I don’t think you can get much of that information out of your IT reporting structures. It’s a matter of putting down the different process equipment and having a cross-functional team putting a grid together. The rows on the left-hand side might be press punching equipment, and the columns across the top are different products. Let’s then see if we can come up with some families.

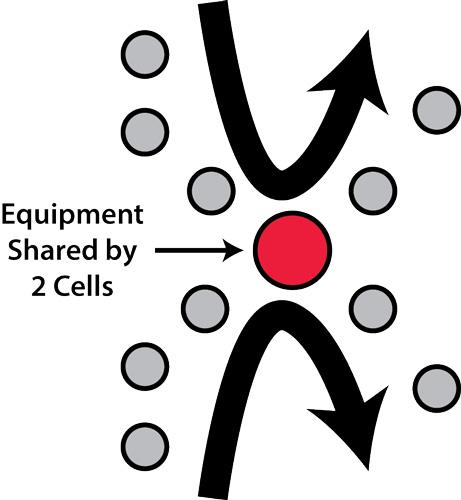

Figure 1

If equipment can’t be moved, lean assembly changes have to occur around this stationary object. In this model, two cells share one common piece of equipment.

The shop might make 200 different products, but the focus should be on 20 because that’s 40 percent of the volume. You’re going to gain a lot of efficiencies, reduce a lot of waste, and come up with other ideas for the other 60 percent.

FAB: When it comes time to move equipment, do some of the common process layouts used in lean manufacturing work in high-mix, low-volume environments?

Mikulak: Oh, sure. You’re going to come up with some things that we call monuments or what some people call anchors. There are things you’re not going to go change. They’re just too expensive to change [see Figure 1]. They’re used by half the different product mixes. Maybe it’s a heat-tempering operation or a big oven.

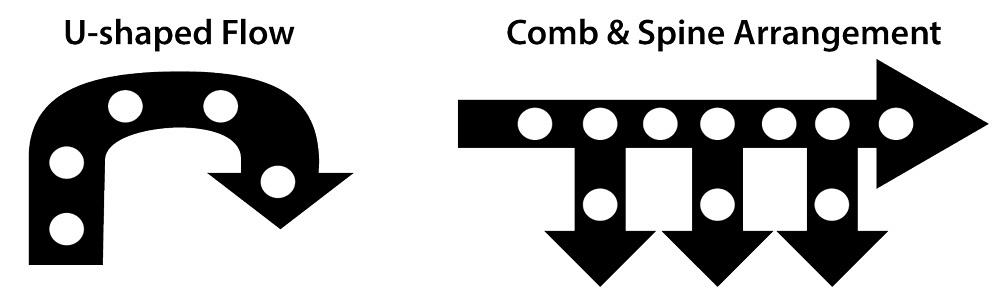

So then it’s a matter of having your product flow get into that unit from a variety of different ways. Then you’re into different types of flows that all take place in any kind of lean manufacturing. It might not just be a U-shape [see Figure 2]; it might be a spine and combs [see Figure 3]. You’re going to skip a lot of different process steps for some product lines. But the same concepts are going to work from that standpoint. It’s just not going to be as simple to do.

FAB: How is scheduling addressed in this type of effort?

Mikulak: Let me go back to rearranging, and then I’ll address scheduling. One of the things that really works well in the type of mix you’re talking about is to put equipment on wheels with quick disconnects for air or electric. That way you can bring it in and bring it out. Not every piece of equipment will work that way, but some will. That’s part of your setup for that run.

Scheduling is one of the crucial things. Too often people in scheduling are left out of the mix for too long, so they’re still scheduling the old way when the new lean concepts are implemented. They have to understand why it’s so important to schedule differently, and the concepts of safety stock and the like have to be forgotten. You need to have those folks take a leap of faith and believe this will really work. They need to know that we’re going to cut down on our defects because we’re going to have quick feedback from the processes to create information quickly. It’s going to be a better way of servicing our customer mix. Not involving people in scheduling right at the beginning is one of the major pitfalls.

FAB: Does this require a big investment in scheduling software? Can old ways still be good ways?

Mikulak: The old ways are the better ways when you’re dealing with scheduling for lean manufacturing. We’ve seen more companies become successful by removing the big ERP systems than anything else.

The ERP systems and the old accounting systems—it’s almost anti-intuitive to get rid of them when you have spent so much money on them and trained everyone. But without them, you’re back to people making decisions, as opposed to the software doing it.

Figure 2 and 3

(left) The U-shaped work flow is arguably the most common layout facilities use when implementing lean principles. Despite the shape, it is simply a variation of straight-through flow.

(right) The comb and spine arrangement works well for assembly operations when products exit the process flow at various levels of assembly. This layout might be suitable for fabricators with jobs that fall into common product families.

FAB: What questions might fabricators ask as they are investigating developing a new cell area or new assembly space?

Mikulak: A lot of them seem like they’re common sense, but they’re really important from a cost standpoint.

Do you have the head space? Take a look especially at the Northeast, where there are a lot of old factories that might not have the ceiling height they need for cranes. Is the floor set up to handle this type of equipment? Does it have the loading? And do you have power distribution?

And once you have all those, where’s the best place to put something? Do you have loading/unloading and shipping docks in the right place? The dense stuff is easier to move than the bulky stuff. Bars of steel are easier to move than cartons of pillows. You want to have the bulky stuff ending up closest to the shipping area.

FAB: Is more open communication a natural occurrence once a company starts investigating lean manufacturing layout and practices?

Mikulak: Communication has to be fostered. I’ll give you some stories about what has held some firms back.

They may have had a long-term employee that’s crucial and he’s known as the best firefighter they’ve ever had. In some of those cases, the firefighter—and he’s really good at fighting fires and knows everything to do when there’s a problem—will make sure the solutions never happen, because then his job will be gone.

In some facilities, the shift supervisor is very well-intentioned and very good technically, but had to be removed from the job because he just couldn’t allow some of these things to take place that would eliminate fires from happening.

In both cases, they fought against the systems. Not overtly and not maliciously, but their importance and value to the organization would be diminished because there aren’t any more problems. What am I going to do? So they would make sure some of the changes and communication between people didn’t happen.

You really have to value the people running your processes—the operators. They really know what’s happening. It’s not always what the procedure says.

FAB: I’ve been in facilities where they really get lean, and the joke is that the interior of the facility never looks the same from six months to the next six months. Things are always moving. Is that accurate when a company really gets what’s happening, particularly when they have a customer base that provides work that’s dynamic and that changes on a frequent basis?

Mikulak: Oh yeah. It is always changing. It’s why you don’t want to build inventory, because whenever you put something in inventory, people always want something different. What you’re selling is changing.

Even minor changes should mean your process has to change. If you have something stable, that’s great. Now it’s time to say, “Where’s our weak point? Let’s go work on that.”

FAB: When an organization gets that kind of momentum, do you find they will have success with this on a continuing basis?Mikulak: They do have success on a continuing basis. The pitfall is when there are senior leadership changes. It doesn’t happen in the owner-operator type settings. When they understand it and get it, they keep it going. It happens more in a facility that’s a division of a large organization, and they move on somewhere else.

Maybe based on the strength of the people behind them that have taken over, they may still continue that and improve on it, but you can also bring in someone that says, “This isn’t the way we need to do it.” That can stop everything.

FAB: How would you gauge your manufacturing clients from 10 years ago? Is there still a vast chasm of efficiency that needs to be bridged? Have people gotten wind of what they need to do and are following through?

Mikulak: There’s no question that we’re better off than we were 20 years ago and probably 10 years ago. But there is so much more that can be done. Even the leading companies—the ones that we’ve used as benchmarks and suggested others visit—are bringing people in and showing them what they’ve done. And when those people come in and ask questions, that opens up new ideas. Even the leading companies continue to get better. So once you improve, you realize you can keep getting better.

Even in the top tier, the organizations have just scratched the surface.

FAB: Any final advice for fabricators hoping to set up a more lean assembly operation?

Mikulak: They really have to start with the 5 Whys [the repetitious asking of the same question to determine the root cause of a quality concern or a defect]. Just moving stuff out of your organization, you get a better view of what’s happening. And you can say, “How can we tighten things up physically as well as from the standpoint of less waste in the process?”

It’s such a simple process, and everyone says, “Oh yeah, we do that.” But we’ve gone in as consultants and people say, “You charge us all this money, and you had us take you on a tour and asked us questions about the process flow. Then you had us clean up the place and move things around, and that’s it!” But it pays off. Just those simple things. Everything else moves from there. But it’s a matter of making sure what’s in the facility is going to be used. If it’s not going to be used, put it somewhere else.

It’s always easier to go into somebody else’s facility and see what to change. That’s why we have people come into our organization and give us feedback. You may be able to help others, but you can’t always help yourself.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI