TruBend and TruPunch Sales Engineer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

4 ways to improve time per bend

For a fabricator to make money, the press brake needs to be bending--not waiting to be used

- By Jamie Crandall

- March 4, 2015

- Article

- Bending and Forming

The goal of any lean bending operation should be to keep the operator bending parts at the press brake as much as possible, not preparing to bend parts. Photos courtesy of TRUMPF Inc.

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from Jamie Crandall’s conference presentation at FABTECH®, Nov. 11-13, 2014, Atlanta.

Metal fabricators are well aware that customers pay for the process of turning sheet metal into specified metal parts. What they sometimes don’t realize is that these customers are not paying for any activity that occurs outside the actual designing and fabricating of those parts.

That is never more evident than when you watch an operator at a press brake. Have you ever noticed the operator walking from one end of the press brake to the other in between bends to consult or make adjustments to the controller? Have you witnessed the operator spending an inordinate amount of time going from station to station to station on the brake to complete one bending job? How many times have you seen a press brake sitting idle as the operator programs the next part at the controller?

All of these types of activities increase the time it takes to process a bending job. This reduction in productivity directly affects the fabricator’s ability to process parts in the most profitable manner. The sooner quality parts are delivered, the sooner the fabricator can be paid for the work.

Fortunately for the fabricator, bending time improvement can be achieved with better planning and modern technology. These four suggestions can make a big impact on reducing the time per bend at the press brake.

1. Consider a Mobile Control

A control mechanism located closer to the press brake operator and the bending action (see Figure 1) can help to eliminate the need to interrupt the bending of parts to address something at the main controller, which might be several feet away on large machines. This mobile control basically mimics some of the same functions as the main controller, only it is right in front of the operator.

The control can provide on/off cycling for a bending job. It also can be used to turn tool clamping on and off to speed along the often time-consuming process of tool changeover.

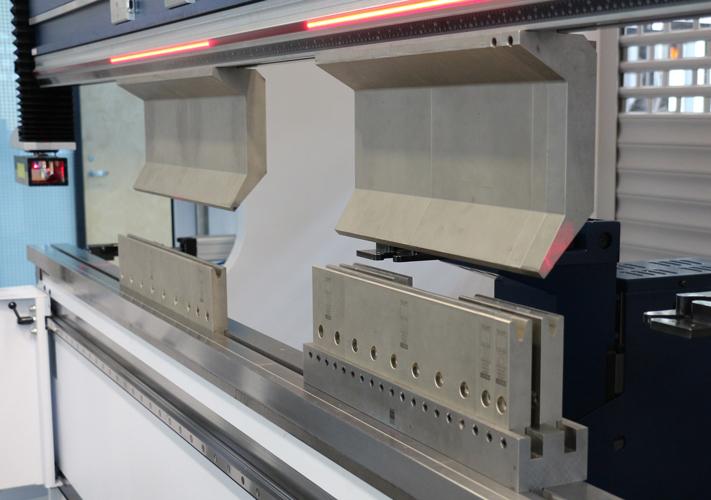

Also aiding in tool changeover are optical setup and positioning aids. These lights, located right above the tooling clamp, are turned on and off by the machine control and direct the operator where to place tooling along the length of the brake. This feature makes a big impact on bending productivity for those fabricators that do a lot of staged bending that requires the operator to place multiple tools in exact positions. It is even more helpful for press brake operators that may not have much bending experience or are not familiar with a particular bending program.

2. Figure out the Correct Part Orientation

A part programmer without a lot of bending experience won’t give a lot of thought to the number of times a press brake operator will have to manipulate a blank or flip it to finish one bending job. That’s unfortunate because additional material handling can add unnecessary time to the overall process.

It also creates a greater potential for operator fatigue, particularly with large parts (see Figure 2). Anything that can be done to minimize part handling of large and awkward parts is good news for the individual standing in front of the press brake for an entire shift.

Figure 1

This mobile control can be used to stop and start the bending cycle or to turn the tooling clamping on or off. It allows the operator to make the machine commands in front of the press brake, eliminating the time associated with walking back and forth to the main control unit.

By observing the actual bending process in action, an experienced eye may be able to switch the order of bends to reduce the amount of flipping required to complete the part. If it normally takes an operator—or even two given the size of the blank—as much as five to eight seconds to flip the material, regauge, and start the next bend, the elimination of a flip or two can mean more bending instead of material handling.

3. Optimize the Bend Sequence

If left to their own devices, a press brake setup person or an operator might not necessarily be preparing a job in the most efficient manner. Some jobs might be set up in a way that requires the operator to walk the entire length of the brake to accomplish bends at each station to finish one part. It’s an effective plan, but not an efficient one.

Modern bending software takes the inefficiencies out of the bending sequencing. It sets up the bending sequence to accommodate the maximum number of bends in the minimum number of stations possible (see Figure 3).

This will improve the bending time per part and also keep the operator fresh by eliminating unnecessary movement around the press brake.

4. Introduce Offline Programming

Plenty of metal fabricators still program parts right at the press brake. Such an approach might be related to having the press brake expertise already on the shop floor, or just a recognition that the process has proven sufficient in the past and likely will remain so in the future.

The problem is that the pressure is on the operator to finish that programming as soon as possible so that the brake can get back to bending parts. Not much thought is given to furthur investigating the bending job to discover the most efficient means to accomplish it.

For example, offline programming provides an opportunity to simulate the bending process before it hits the shop floor. The programmer can observe multiple ways of bending a part and determine which approach will result in minimal material handling and optimal tooling setup.

The programmer also can rely on the software to look beyond the current job. The software can be used to control toolstation setups and identify those parts that might be able to be processed using the same setups. This can help the operator set up jobs more quickly and reduce the downtime between bending jobs.

A Note About Automated Bending

Both OEMs and job shops are now using bending cells with automated tooling setup and robotic material handling and part manipulation at the press brake (see Figure 4). The benefit is obvious: Because no operator is present, the time per bend is maximized. In fact, these bend cells can be run at night and on weekends, when no staff or skeleton crew is present.

With the advancement of control software, a fabricator doesn’t have to worry about teaching the robot for each bending job. A programmer uses offline programming to create a bending job that instructs all aspects of the cell: press brake, bending robot, grippers, and conveyor technology. One programming interface is the gateway to controlling all of these different functions.

Figure 2

A critical review of a bending job might reveal a new order of bends that reduces the amount of flipping of large parts. This small alteration to a bending job involving large and awkward parts can save time and lighten the load for the press brake operator.

Additionally, automatic caculation functions determine the optimized tooling setup, the bending sequence, and the exact gripper position. The shortest bend cycle possible is the result.

Automated bending may not be suitable for all fabricators, but it is a reminder of all the shortcomings that need to be addressed in manual bending operations. Steps can be taken to reduce the time per bend. It’s just a matter of taking the first step toward improving bending productivity.

About the Author

Jamie Crandall

Farmington Industrial Park

Farmington, CT 06032

860-255-6000

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI