Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Dutch metal fabrication: About flow

How small order quantities shape metal fabrication in Northern Europe

- By Tim Heston

- November 4, 2015

- Article

- Bending and Forming

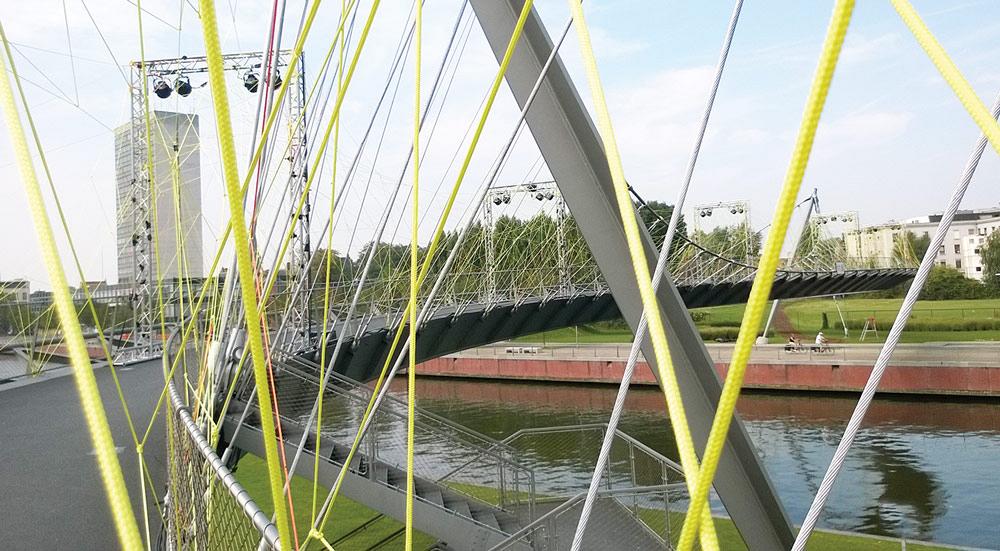

The people of Kortrijk know how to spend a Sunday. They sit, eat, drink, and watch the flow—including the flow of the Leie, a river central to this Belgian town’s history (see Figure 1). The English called it the Golden River, and for good reason. It flows at just the right speed, not too fast and not too slow, to loosen the flax fibers growing nearby. If the river flowed any differently, flax wouldn’t have thrived, and Kortrijk would be a very different place.

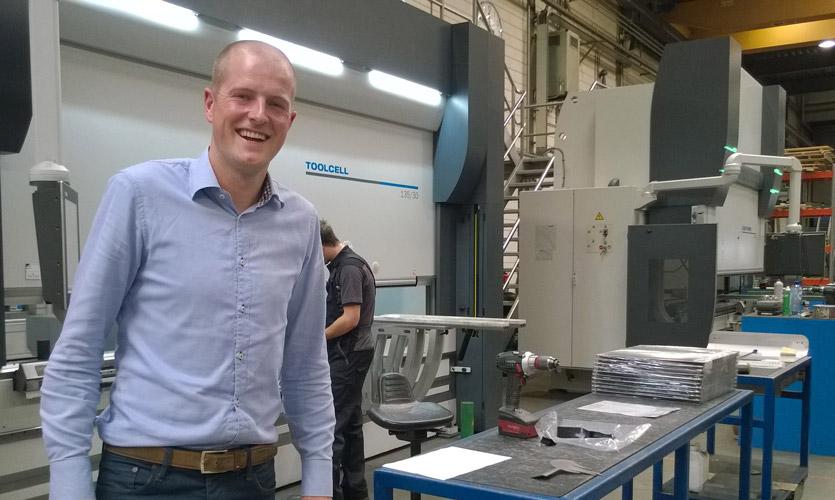

Two days later I stood by a line of press brakes at Van Bussel Metaaltechniek, a job shop across the border in Holland. Chatting with one of the shop managers, I saw operators move from one brake to another, forming one small batch after another (see Figure 2).

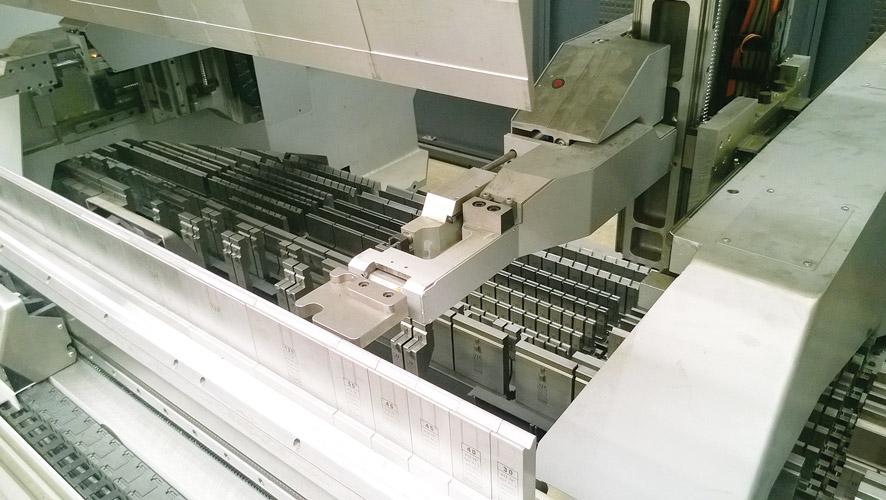

One brake featured automatic tool change, with backgauge fingers doubling as tool changeover devices that removed and replaced punches and dies (see Figure 3). The changeover took a minute, and the operator bent the first part. The machine had adaptive forming technology, with lasers that measured and allowed the brake to adjust the bend angle on-the-fly. The result: The first part was a good part. That was a good thing, because the operator had to bend a batch of only three before moving on to the next job.

Thing is, when talking with shop managers, I didn’t notice all these details initially. What I did notice were small batches of parts being put on carts, which were rolled to the next operation. Stationary work-in-process (WIP) was about nonexistent.

That was thanks to flow. Too fast and huge piles of WIP probably would have collected ahead of the press brake area; too slow and machines would have been starved for work. But flow the parts just right, and the shop can turn around certain orders within hours.

This theme pervaded an early September trip for the North American industrial press, hosted by machine-maker LVD, which is based in Gullegem, Belgium, not far from Kortrijk and its Golden River. Fabricators can adopt technology to cut, bend, and weld as quickly as ever. But all those investments really don’t pay off unless a shop integrates them to achieve one overarching purpose: to shorten the overall order-to-ship cycle for as many jobs in a shop’s product mix as possible. When a shop achieves this, it has the right flow.

A Little of This, a Little of That

Many Dutch fab shops do business with customers who order extremely small quantities frequently—one of this, a dozen of that—that must be delivered in hours or a few days.

On top of this, most customers don’t give shops repeat orders of identical products. It’s all about customization. The first order may comprise various materials bent to different angles, or painted another color. This means that each part requires new cutting, bending, and welding programs.

Running small jobs naturally reduces a job’s batch size. But if you have lengthy setups, be it in front of the brake, welding cell, or any other work center, it wouldn’t take long for a lot of small jobs to gather before the operation bottleneck. As WIP grows, so does the overall lead time.

The same concept applies to the front office. If loads of small orders pile up (basically front-office WIP) in engineering, estimating, and order entry, all waiting for questions to be answered or programs to be made, lead times become longer.

Figure 2

Thomas Waals, commercial manager at Van Bussel Metaaltechniek in the Netherlands, stands next to two carts carrying three different orders—one for just one piece, another for about a dozen, and another for three pieces. Behind him is a press brake that changes its tooling automatically.

The Necessity of Fast Changeover

If customers demand only a handful of parts or assemblies at a time, it’s impractical to spend much time on machine setup. Why spend 15 minutes on machine setup for an order of six pieces? You spend longer on setup than production, which makes the pieces prohibitively expensive. It also doesn’t make sense to produce more parts than what was ordered, because these exact parts might not be ordered again.

This is where automatic tool change comes into play, which has become especially valuable in forming. The shops on the media tour all used LVD’s ToolCell press brake, which has backgauge fingers that double as tool manipulators to pick, place, and rearrange staged setups of punches and dies between jobs.

Adaptive forming also plays a role here, minimizing or eliminating tryout pieces, which can add serious costs to a job of only a handful of parts. All brakes at these Dutch shops used LVD’s Easy-Form® Laser technology, which uses lasers to measure and feed back angle information to the brake controller, which makes program adjustments on-the-fly.

Right Information, Time, and Interpretation

The fastest changeover in the world and the most intelligent adaptive bending won’t make much difference if the shop is fabricating the wrong part at the wrong time.

Manufacturers in Europe are pushing for a concept called Industry 4.0, dubbed the “fourth industrial revolution,” following the loom in the 1780s, mass production in the beginning of the 20th century, and the factory automation that began at the end of the 20th century.

The fourth revolution goes a step further. In a recent company publication, LVD’s Wim Serruys, director of engineering, put it this way: “Industry 4.0 changes the game by adding intelligence to the mix and not just aiming for smarter machines or software, but a smart factory; a factory where machines, products, tools, and software communicate with each other. This is where we’ll see the most adoption in the sheet metal industry; machines will become social, sharing information with manufacturing execution systems. Decision-makers get real-time insights from the shop floor and instant control of production processes.”

During the press tour, LVD officials brought members of the media through their products that support the concepts behind Industry 4.0—how the company’s CADMAN®-JOB production control software draws information from enterprise resource planning (ERP) software and schedules jobs in cutting and bending; how people sorting parts after cutting and bending can use the TOUCH-i4 tablet to sort orders, validate that parts are good, as well as help with tracking and labeling.

All this involves not just getting the right data, but also interpreting that data in a meaningful way. How long are machine setups really taking? If a machine is down, why is it down? If it’s available but not producing, why? If it’s producing more parts than what was ordered, why? These and similar questions become all the more important when you’re fabricating a little of this and a little of that.

Good Part Flow, Good Cash Flow

The root causes of misinformation often occur at the very start of the process change, in the front office—a trend the people at Asten-based Van Bussel Metaaltechniek discovered eight years ago. Customers of the Dutch fabricator would send flat-pattern DXF files along with the 3-D CAD file. The thinking at the time was that Van Bussel needed to push jobs out to the floor as quickly as possible to ensure that the shop’s automated lasers churned out parts to capacity.

As Thomas Waals, commercial manager, explained, “A lot of times we found that when parts reached the press brake, we discovered it was the wrong part.” The DXF happened to be an older revision from the 3-D CAD file. “It cost us so much money.”

Figure 3

On this press brake, the backgauge fingers double as a tool changeover device that removes and replaces punches and dies, all stored behind the bed of the brake.

Van Bussel fabricates a lot of stainless steel for food processing and related sectors, and this means that continually scrapped parts add up to serious money.

“So starting eight years ago, we decided that we first finalize the 3-D drawing,” Waals said, “and then make the DXF with the exact geometries we need, and only then do we go to cutting and bending. It was a new mindset.”

Like some fab shops in the states, Van Bussel operates as a kind of hybrid, part custom fabricator and part project-based manufacturer. This only adds to all the variability in engineering and production. No workday is exactly like the one before it.

As a custom fabricator, Van Bussel accepts an order—again, mostly for just a handful of parts—and usually turns it around within 24 to 48 hours. The vast majority of parts undergo both cutting and forming, and some might require limited welding and assembly work.

The other portion of revenue comes from project-based work in which the fabricator produces complete systems, like filtration tanks, conveyors, and other machinery used at food processing plants. The time from the initial order to final shipping and installation is between six and eight weeks.

Most of the company’s 25 employees aren’t on the shop floor; they’re in the front office, in engineering and programming. Parts are engineered and nested, then sent to the shop floor as quickly as possible.

The company uses dynamic nesting to its fullest to maximize material utilization (see Figure 4). Waals explained that this is another reason that precision in forming, and the use of adaptive bending, is so essential. The shop rarely needs to maintain consistent part orientations in its nests because of grain-direction issues in forming. The lasers measuring the angle during the bend allows the brake to adapt and produce the correct angle, no matter the grain direction.

Programmers wait as long as possible before producing a nest for a machine, filling a sheet with as many small jobs as possible. They’re also careful not to nest too far out in the schedule—though for many jobs the programmers don’t have that option anyway; for many jobs, the parts are due the very next day.

After the operator forms the small batch, he places them back on the carts. When parts are on carts, they’re moving. And when parts are moving, they’re getting closer to shipping. When parts ship, the shop gets paid.

Mathijs Wijn, district sales manager for LVD in the Netherlands, pointed to a thick piece of stainless steel in Van Bussel’s raw stock inventory. “That’s some expensive material right there.”

Figure 4

Van Bussel uses dynamic nesting whenever possible, grouping many small jobs on one sheet. According to the company, adaptive forming at the brakes has given laser programmers the freedom to nest parts in various directions, including the orientation of some parts that otherwise might be sensitive to grain direction.

This, Wijn added, is one more reason that quick turnaround is so important to Dutch companies like Van Bussel. In the states, if a fab shop has good service center support, it often minimizes its raw stock inventory. Outside of special materials, they opt for just-in-time delivery of common metals.

In the Netherlands, the situation is different. For a company its size, Van Bussel has a fair amount of raw stock. The company receives discounts for buying stainless at a certain volume, and it receives even bigger discounts if it pays for that material in eight days or less. That requires a lot of ready cash.

Material is usually the biggest line item on any shop’s balance sheet, so these discounts give fabricators with good cash flow a serious competitive advantage. What gives Van Bussel that good cash flow is its extremely short order-to-ship cycle, made possible by flexible machines, software, and good manufacturing practices.

Automating the Front End

Antal Driessen, director of Metaalcenter Driessen BV in Weert, has kept his eye on the order-to-ship cycle for years (see Figure 5). That’s why he tends to get rid of the old to make way for the new.

He doesn’t hold on to old equipment. Driessen feels that the long setup and processing times of older equipment hurt more than help overall manufacturing capacity, and that’s because those older machines prolong the overall manufacturing cycle. Again, that short cycle improves cash flow, which opens up more opportunity for purchasing (material discounts), not to mention future capital investments.

These investments include more than 200,000 euros’ worth of custom software over the past seven years. All this software investment is designed to free what became Driessen’s greatest constraint: preproduction.

The problem became apparent when customers began ordering small quantities, which became the new normal after the 2008 financial crisis. The fabricator had perfected its flow on the shop floor. The shop effectively operates with a “single-sheet” part flow. It groups disparate small orders on one sheet, avoiding remnants whenever possible. Its automated laser cutting systems offload cut parts, where operators sort them.

These parts flow in small batches on carts (no fork trucks) to the press brake area, where again the company uses automated tool change technology to speed the flow of disparate orders through forming. Then it’s on to welding, painting (which is outsourced), and shipping. For some jobs, the company effectively had shortened its manufacturing cycle to mere hours.

But then there was the quoting problem. Like in the States, Dutch fab shops must answer a lot of request for quotes (RFQs). The shops win only a portion of jobs, of course. Moreover, when those jobs involve only a small number of parts, quoting and engineering time becomes a problem.

As Driessen put it, “I used to fabricate 1,000 pieces, and that took me 10 hours to produce. I had one hour of preproduction time. That’s not a problem. But when I have only 10 pieces, I sometimes have only minutes of production time, and yet it still takes me one hour of preproduction time.”

Figure 5

Antal Driessen, director of Metaalcenter Driessen BV, stands in front of the company’s press brake with automatic tool changing. He has worked with software developers for seven years. The result: Much of his company’s quoting process has become automated.

From this came the shop’s latest advance. Driessen worked with software engineers who produced custom software that automates quoting for jobs that are cut (both flat sheet and tube) and bent. It takes information from customer 3-D CAD files (usually in STEP format), unfolds it, and calculates cutting and forming times based on predetermined rates, all drawn from data gathered in a standard Excel file.

Driessen added that it took a lot more than just building an Excel file, of course. All the variables took seven years to perfect, after all. But the end result, which went live this year, has helped shorten his order-to-ship cycle dramatically.

For certain products, Driessen has implemented a system in which customers can choose basic modular components and, in effect, build their own basic 3-D model online, then submit it for an RFQ. The online system uses parametric modeling, and it’s suitable only for simple jobs like stairs and railings, but the system has opened the door to many small jobs that wouldn’t have made business sense to take on without such software.

Driessen’s operation is a good showpiece for proving the potential of Industry 4.0. XML files flow between shop management software to machines, and after fabricating a job, the machine controls send XML files to the management software. Now that kind of seamless flow of data occurs on the front end. Quoting and engineering now occur in minutes.

Driessen’s custom software has made preproduction a consistent variable. Most jobs take only minutes to quote, whether the run is for one piece or 1,000.

As Driessen put it, “We can now earn money when we fabricate just one product.”

More Than Saws

Kinkelder Lasersnijtechniek, in Zevenaar, is a custom fabricator that operates as part of Kinkelder, the maker of metalworking saws. About 10 percent of the work entails the laser cutting of saw blank profiles, many out of high-speed steel grades, which are then sent to the larger Kinkelder facility across the street, where the blanks undergo grinding, hardening, and final finishing (see Figure 6). Yet 90 percent of the fab shop’s work is entirely custom.

The operators themselves perform the nesting operation, which occurs only several minutes before the blank is sent to the machine and the laser commences cutting. “This changed about six years ago,” said Michèl Beek, technical manager. “Many of them thought that they were operators, so they just operate the machines. But they found that nesting wasn’t a complicated job. Sometimes the operators just aren’t aware of what they can do.”

Parts flow (again, on small carts, not fork trucks) from the laser to the brakes, including one with automatic tool change. Beek conceded that he can’t use this machine for every part. Some parts are just too big or require special tools. For instance, a box may have a deep form that requires tall tools, which the manipulators in the brake just can’t handle. But usually if a job, especially one with complex forms, can be sent through the automatic tool change system, it is.

Ron Bosman, manufacturing engineer, pointed to an unusual program at the brake with automatic tool changing. The backgauge fingers in the simulation were set extremely high (in the R direction) to gauge the back of a part with a large flange that swung upward behind the tools.

Figure 6

At Kinkelder’s custom fabrication operation, a profile for a circular saw is cut on the laser, shortening processing time at the company’s main saw blade plant across the street. Note the material handling carts. The plant uses few fork trucks.

Usually a backgauge couldn’t possibly move that high to gauge that edge. But as Bosman explained, because the backgauge doubles as a tool changer, the fingers have an extremely large range of movement, which opens the door to more gauging possibilities.

Disparate Shops, Common Threads

Like in America, fab shops on the LVD tour in Holland vary widely, and they’re difficult to categorize. Bergeijk-based Bax Metaal launched in 1990 as a custom fabricator, making everything from a conveying shaft for the food processing industry to a children’s exhibit (involving some extremely complex, irregular geometries) at a soccer museum (see Figure 7) .

In 2011 the company also launched a product line of its own, a flat-part deburring and graining system that features an under-the-belt vacuum powerful enough to keep very small parts flat throughout the finishing process. Currently the product line represents about 10 percent of shop revenue, but according to Bax Managing Director Anton Bax, the company expects that product line revenue to increase in the coming years.

Doeschot, based in rural Hengevelde in the middle of quintessential Dutch farmland, specializes in metal buildings. It is able to produce both the structural beams and plates as well as complex ornamental elements, thanks to its in-house laser cutting and bending capability—again, with automatic tool change. The company uses Tekla BIM (building information modeling), exports components to SolidWorks®, which in turn exports to the company’s production software including LVD’s CADMAN-B for offline bend programming.

It’s also looking to diversify beyond the construction business, especially considering the hit the company took after the financial crisis in 2008. The construction market has since recovered, but its quest for diversification continues.

Common themes of quick changeover and small batches pervaded all the shops on the tour. But the overarching message involved communication based on real shop data, not assumptions or outright guesses.

Bax pointed to a simple board his company has set up to aid in communication. It shows where jobs are and their status in relation to the due date; it also provides space for workers to post any issues they may be having. Bax added that the company plans to upgrade this to an electronic system with flat screens posted throughout the plant.

Regardless of the technology used, the intent is the same. With the right information presented at the right time, a custom fabricator can create flow like the Leie, the Golden River, flowing steadily through the heart of Kortrijk—not too fast, not too slow, but just right to do the job.

LVD Strippit Inc., 12975 Clarence Center Road, Akron, NY 14001, 800-828-1527, www.lvdgroup.com

Bax Metaal, Bergeijk, Netherlands, www.baxmetaal.nl

Figure 7

Technicians at Bax Metaal review the fabrication procedures for a new children’s exhibit at a soccer museum.

Doeschot BV, Hengevelde, Netherlands, www.constructiebedrijf-doe schot.nl

Kinkelder Lasersnijtechniek, Zevenaar, Netherlands, www.kinkelder.lasersnij techniek.nl

Metaalcenter Driessen BV, Weert, Netherlands, www.mcdriessen.nl

Van Bussel Metaaltechniek, Asten, Netherlands, www.vanbussel.com

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI