Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Technology Spotlight: Modular design meets the press brake

Multi-frame” approach reduces the mass of high-tonnage machines

- By Tim Heston

- March 3, 2017

- Article

- Bending and Forming

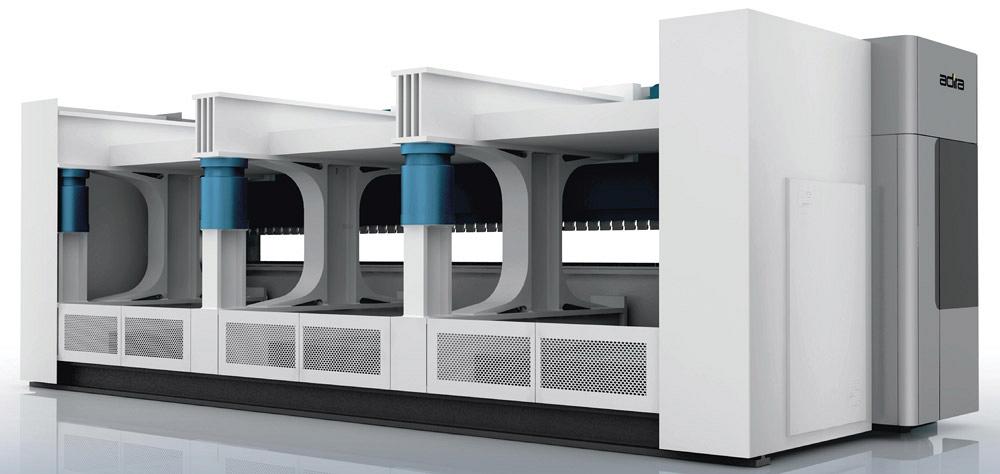

The HD Greenbender has a modular design that accounts for deflection using supplementary hydraulics instead of a conventional crowning system.

It’s a big leap for a heavy or an industrial fabricator to invest in a massive press brake. It can give a shop some bragging rights, for sure, but installing such massive machines can be arduous affairs. They require foundation work (pit installation), and they aren’t the easiest to transport.

Big press brakes are big for a reason. Such monster machines exert tremendous force, so engineers add mass to the machine frame to deal with that force. The machine frame deflects, hence the need for crowning devices integrated into the brake’s lower beam.

But recently engineers at Portuguese machine tool manufacturer Adira Metal Forming Solutions S.A. developed a way to deal with such force in a different way. According to the company, the approach, designed into its HD Greenbender line, eliminates the need for pit installations by lowering the overall mass of the machine and making the design modular. And as the company explained, the machine has no need for a conventional crowning system.

Most press brakes are built using a C-frame, with two side housings and two beams, one fixed (usually the bottom beam) and one moving. The new approach uses a T-frame, not just on either side of the brake but also spaced evenly across the press brake’s width. The company calls this its “dematerialized” approach.

As Rui César, project applications manager, explained, “On a normal press brake, the bending is supported by the C-frame, which deflects upward when the cylinders are actuating. In this system, since the frame was dematerialized, we cannot use the same strategy, which could compromise structural integrity.

“Since we use different structural modules,” César continued, “we have several support points. Instead of having two lateral C-shaped frames and a central beam, we place intermediate supports. This allows us to minimize deformation. And the distance between frames, which can be critical on long machines, doesn’t present a problem.”

Adira calls this a “multi-frame” design. The space behind the tooling isn’t open. Instead, the T-frames across the machine introduce a throat depth across the bed, like a tandem or triplet machine. Still, sources emphasized that this is not a tandem or triplet system, but instead one machine with one upper and lower beam. Regardless, sources said that the T-frame allows machines to be designed with a very deep throat depth between the tooling and the pillar of the T-frame behind it (see photo).

“The modules are topographically optimized to their size and required loads,” César said. “If a different [open] height or [throat] depth is needed, the same compensation concept may be used, but it would require a new structure.” Using software, engineers can run simulations and tailor the design around a specified throat depth, as well as open height and stroke depth.

On each T-frame are two hydraulic cylinders, one in front and one at the rear of the machine. The two cylinders work in concert and, by doing so, can exert bending force while also compensating for deflection. This, sources said, eliminates the need for a conventional crowning system.

“The rear hydraulic actuator applies an upward force, hence compensating for the normal deflection of the structure,” César said.

“When the main cylinder exerts force, the rear cylinder compensates for deflection and keeps the system balanced. There is also dynamic control between the two [cylinders], using electronic control with sensors.”

Each T-frame is part of a module that includes a hydraulic cylinder in the front and (as shown in blue) in the back.

Last year the company introduced a 750-ton prototype, with each of the machine’s three cylinders applying 250 tons of forming force. “The total force will be proportional to the number of modules that you use,” said Filipe Coutinho, product development engineer.

“We can go up to 500 tons with each frame,” César said. Each T-frame is part of a module, and if a machine uses six modules, each exerting 500 tons, the machine would have a total tonnage of 3,000 tons. César added that the limitations would involve the dimensions and weight for transport.

Regardless, they said that the approach may open up the potential for heavy forming to more fabrication facilities, with smaller, manageable modules arriving on-site and then assembled together into a machine that, ultimately, can bend seriously thick plate.

Images courtesy of Adira Metal Forming Solutions S.A., 351-226-192-700, www.adira.pt.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI