- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fabricator turns up the heat

Laser welding improves weld appearance, strength, defect rate

- By Eric Lundin

- June 1, 2015

- Article

- Laser Welding

With a rich history of innovative metalworking techniques, A. O. Smith Corporation, Milwaukee, has long been a leader in metal forming and fabrication. Founded as a family-run machine shop in 1874, the company used its expertise in forming metal tubes to create a niche in the bicycle industry, first making forks and then bicycle frames. The company later ventured into the new and growing automobile industry. It focused on frames and developed processes that enabled the company to produce one frame every eight seconds.

Also interested in cutting-edge welding techniques, the company’s research and development played an important role in making arc welding the mass production process it still is today. In 1925 the company started manufacturing pressure vessels, and its research in fusing glass to steel led to large, glass-lined, single-piece brewery tanks, which it introduced in 1933.

In 1936 the company patented and introduced the product it is most widely known for today: glass-lined water heaters. This concept quickly became an industry standard and made residential water heaters affordable to the masses. Today the company operates many water heater factories around the world and sells its products under various brand names through both retail and wholesale distribution channels.

New Challenges

This isn’t to say that A. O. Smith doesn’t occasionally encounter a fabricating challenge. Faced with unacceptable downtime on a resistance welding line for burner chamber walls, Travis Salyers, a senior manufacturing engineer for the company, went looking for a better welding process. Co-worker and Welding Engineer Richard Garner suggested laser welding as a possibility. Garner had been investigating and evaluating laser welding for 15 years and thought that the power and reliability of modern lasers would be well-suited to the application. He suggested Salyers contact Weil Engineering, a supplier of short tube, tank, and drum production systems.

The machine Salyers was looking for would have to weld 14-, 16-, 18-, and 20-in.-dia. rings made from 0.048-in.-thick galvanized steel with minimum changeover time. It would have to process 1,200 to 1,400 parts in an eight-hour shift.

Weil Engineering proposed a customized version of its RingMaster, an automated rolling and welding machine designed and built for beer kegs and similar applications. Production steps for the machine would be:

- Destack a single blank from a pallet for any of the diameters or heights required to produce water heater tanks from 30 to 75 gallons.

- Flip the blank up on edge to put it through the vertically oriented rolling station.

- Move it to a laser welding station.

- Weld it into a closed ring.

- Place the finished part onto a conveyor table.

To keep the cycle time as short as possible, the machine is designed with a forming station and welding station that operate in tandem on two different blanks. The vertical design of the machine, with the welding area located inches above the forming station, streamlines material flow through the machine and helps reduce floor space requirements.

To maintain flexibility and machine redundancy, A. O. Smith chose to install the new machine alongside its existing resistance welding system, with a rolling conveyor to take parts from both machines down the assembly line.

Salyers had concerns about the strength, formability, and cosmetic appearance of the weld bead. He considered a few ideas for strength and formability testing stations but decided that, because the welded ring would go directly to the flanging and forming station, any nonconforming parts could be pulled off the line immediately after they fractured or failed. An intermediate testing step simply wouldn’t be necessary.

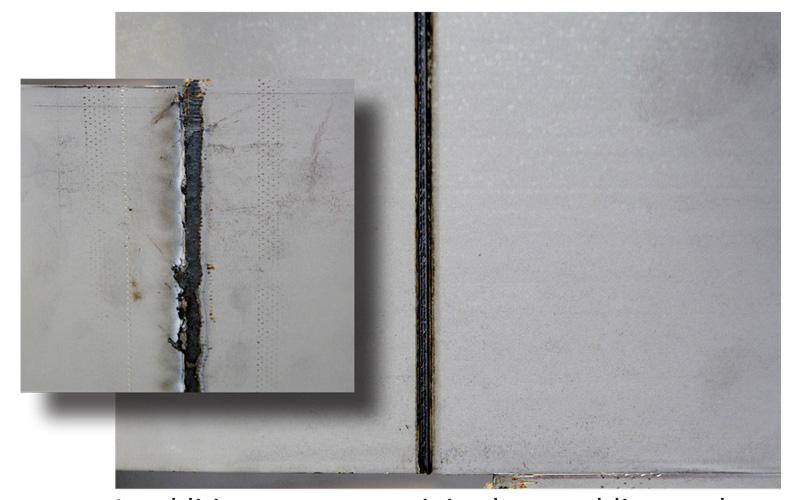

As for the cosmetic appearance, A. O. Smith discovered that switching from an overlap weld to a butt weld was a visual home run. Overlap welds on galvanized steel rarely have a good aesthetic appearance. After the weld heat vaporizes the zinc, the vapor gets trapped between the overlapped surfaces. With no place to go, it escapes through the weld puddle by bursting out. This action ejects material from the molten pool, leaving a cratered weld that is usually weaker than the base material.

In addition to a stronger joint, laser welding produces an aesthetically improved joint for this application.

Less Scrap, Less Inventory

With the new machine in full production for two shifts, five days a week, A. O. Smith has had enough time to quantify the benefits of its investment. First, the welding cell’s uptime has improved considerably, having suffered no significant outages.

Second, the company noticed a significant decrease in its scrap rate; so far, none of the welds have failed in the forming station. The production staff no longer empties a small dumpster twice per shift.

A Look to the Future

Now a $2.2 billion company, A. O. Smith brands include State, American®, Reliance®, GSW, John Wood®, and the A. O. Smith brand. It still has headquarters in Milwaukee and it continues to be an innovator, holding dozens of patents (the latest was issued in 2013). At 140 years old, the company has a spirit of innovation that lives on in the capital equipment it purchases. Its foray into laser welding is evidence that the company keeps up with manufacturing trends, positioning itself for another 140 years of growth.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI