President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Punching on a press brake

Unitized tooling adds versatility to a fabricator's bending tool

- By Henry Llop

- March 1, 2016

- Article

- Punching and Other Holemaking

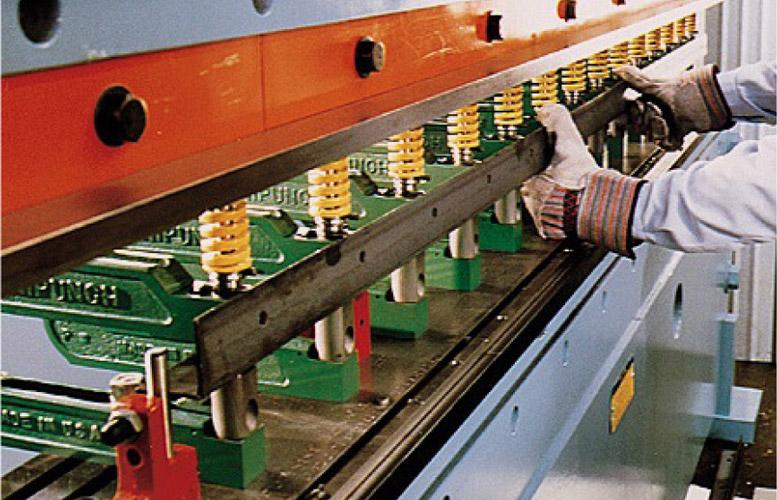

Figure 1

An old press brake gets new life with unitized tooling that can be used to transform the machine into a punching station.

A press brake set up for punching can be another useful tool in a fabricator’s toolbox, and that is why some shops have repurposed an older press brake from bending and forming to punching.

Fabricators who have done so have discovered some competitive advantages. Whether a shop makes its own product line or makes parts for others, the fabricating manager wants to lower costs for better profit margins. The goal is to have quick, predictable, and on-time production so that short lead times can be promised. Who doesn’t want the peace of mind that comes from a reliable process?

In addition, a fabricating manager wants the ability to change over quickly from part to part because that allows for small lots to be run efficiently and for inventory to be kept to a minimum.

Punching with a press brake can accomplish those goals (see Figure 1).

Common Applications

A common application is punching a line of holes; for example, along the edge of a sheet (see Figure 2) in an aluminum extrusion such as door or window trim, in a structural shape such as angle iron (see Figure 3), or even in tubing or pipe.

The method is productive and predictable because all the holes are made with one press stroke.

A die set for punching in a press brake is a long, narrow affair that is relatively expensive and can become obsolete if the part is no longer required. That is why fabricators who need a line of holes use modular press tooling, such as C‑frame tooling mounted in a press brake that was either purchased for punching or was repurposed from bending and forming. And with the modern emphasis on producing small lots frequently, more fabricators are focusing on quick changeover from part to part.

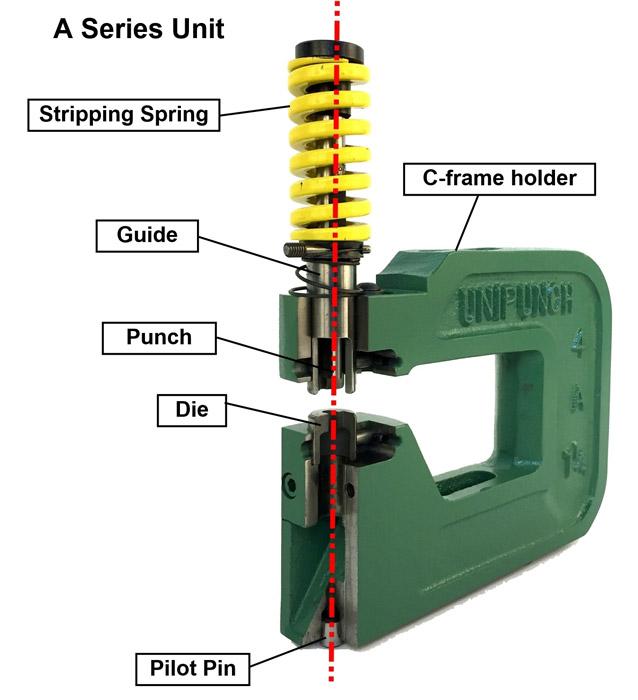

Multiple styles of modular press tooling are available, and each is a catalog of components that can be assembled alongside one another to make a setup to punch and notch a part. For a line of holes made in a press brake, C-frame tooling is suitable for the job. The system also is called unitized tooling (see Figure 4). The precision-machined C‑frame holder accurately aligns the punch and die over the pilot pin, and each unit includes a stripping spring to pull the punch out of the part after the hole has been made.

Most commonly, each unit makes just one hole. Punches and dies for cluster configurations or tandem units are available (see Figure 5).

Efficient Production

For fast changeover from part to part, the C-frame units are mounted on a template (see Figure 6) in a setup that is dedicated to the part for as long as it will be produced on a routine basis.

Setups can be stored close to the point of use. Units in a series have the same die heights and use the same press shut heights. By sticking with the same series of holders and using a common thickness for the templates, a fabricator has no need to readjust the press shut height between parts. These are important practices for fast changeover from part to part.

Hole-to-hole locations, hole size, and the orientation of shapes are defined in the setup and do not change—unless the engineering specifications change. In this case, the units can be repositioned quickly on the template to accommodate the new design.

In time, if a part is no longer going to be produced on a regular basis, the tooling components can be repurposed in a new setup to make a different part. This repurposing of the tooling for a different part can continue indefinitely. The cost of the tooling does not need to be amortized over just the first part.

Versatility in the Tooling

Modular C-frame tooling has a range of capabilities. Holders are available to punch up to a 5-inch hole in 10-gauge mild steel, a 3.5-in. hole in 0.25-in. mild steel, or a 1.125-in. hole in 0.75-in.-thick material. C-frame tooling also is used to punch other materials such as stainless steel, aluminum, copper, and brass.

Holders typically have throat depths of 4, 8, 12, and 18 in. Factors that affect the throat depth are just how far the hole is from the material edge and for what parts the holder might be used in the future.

Punches for standard and exotic shapes are typically available as well. Custom units can be designed to produce clusters of holes. Other applications that fabricators routinely use C-frame tooling for include countersinks, keyholes, corner radii, and trim and part tooling.

In recent years the demand for deformation-free holes in tubing has led to the development of mandrel tube punching units (see Figure 7). This style of unit supports the tube internally to provide a dimple-free hole in single or multiple hole configurations in round, square, and rectangular tubing or pipe.

Admittedly some parts do not lend themselves to being punched in a press brake.

Examples are parts with very large holes, parts with holes that are far from the edge of the sheet, and parts with long contours that can be nibbled with a turret or easily cut with a laser. In addition, a laser can be a great way to produce a repair part for which demand has become infrequent, which means dedicated press tooling is no longer needed.

When to Use C-frame Tooling

A question remains: If a fabricator has an abundance of methods for making a hole, how does he choose? Sometimes the decision is situational.

A shop may be in a position that it has to make parts any way it can to meet a delivery deadline. At that point the shop uses any equipment available. A low-cost and fast process for making those holes makes sense.

Another fabricator may be faced with typical production goals of getting work done quickly without creating a delay that affects downstream manufacturing activities. In this case, the fabricator should focus on the combination of reduced setup time and run time.

Of course, costs are not the same for every holemaking method. Repurposing an unused press brake can be taking advantage of a machine that has long since been fully depreciated and paid for. Getting new life out of old iron may appeal to some fabricators.

Lot size influences the method of holemaking as well. Fabricating shop managers have an intuitive understanding that an optimal lot size addresses upcoming demand and balances that with shop realities. The shop doesn’t want to carry too much inventory, to lose floor space to piles of work-in-process, and to tie up press brake capacity making batches that are too big. Those same managers also want to minimize changeovers on the press brake because a shop doesn’t make money when a machine isn’t running.

If a shop has to have more changeovers, it wants to do them quickly. Modular press tooling set up for quick changeover in a brake is one way to do that. The shop enjoys the productivity of a die set while relying on reusable tooling.

Fabricators that want a toolbox from which to select the optimal manufacturing method according to the shape of the part and how frequently it is required can add a useful tool by repurposing a press brake from bending and forming to punching. Modular press tooling makes that happen, while at the same time boosting production efficiency and minimizing tooling changeover time.

Photos courtesy of UniPunch Products Inc.

About the Author

Henry Llop

311 5th St. NW

Clear Lake, WI 54005

800-828-7061

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI