Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How employees drive a safe work environment

The Dupps Co. boasts an incredible safety record, thanks to its employees who make it happen

Two million of anything is hard to fathom. Two million hours without a lost-time accident is even more difficult to comprehend.

The Dupps Co., a Germantown, Ohio-based manufacturer of rendering systems for the food processing industry, has managed to do that in what could be considered an environment that is ripe for potential accidents. Heavy fabrications are commonly moved across the facility by crane. Lift trucks with heavy loads routinely zip around the shop floor. Grinding and welding, which are a threat to eyes and skin, are commonplace fabricating activities. Manufacturing equipment with the power to crush human limbs is a common sight in the shop. There’s a reason that Dupps requires its employees to wear hard hats and steel-toed shoes on the production floor.

Protective equipment goes only so far, however. The employee has to make the decision to avoid risky behavior that may put him or co-workers in danger.

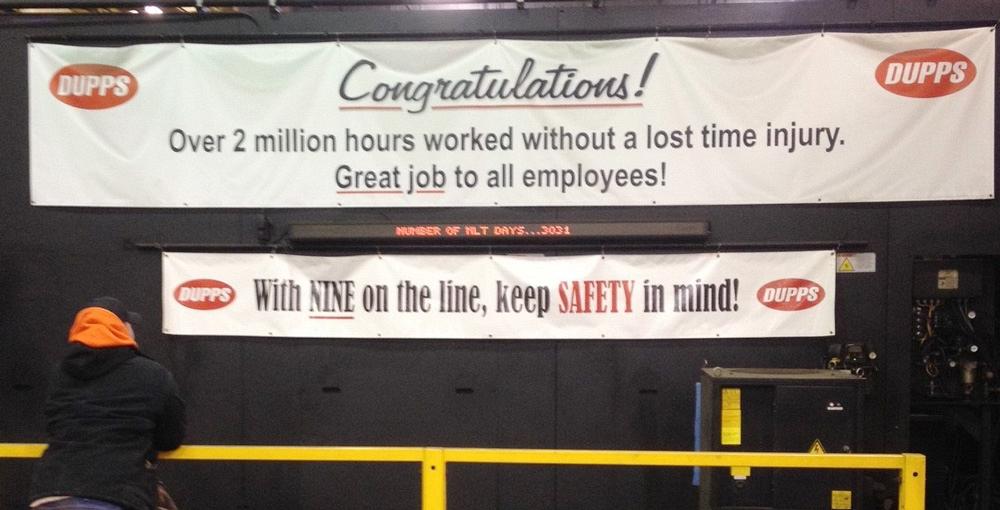

Dupps has achieved this—for eight years now (see Figure 1). The company’s efforts and safety achievements are reasons it was named the recipient of the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association’s 2015 Rusty Demeules Award for Safety Excellence (see Figure 2). (For more on the award, see The Story Behind the Award sidebar.)

Understanding What Dupps Does

To get a feel for the skill and expertise required to make the metal products that Dupps sells, one has to know what rendering equipment is.

In any good business model, waste is undesirable. This is one of the reasons that food processing companies want to utilize every remnant of the animal. These byproducts, such as fat and protein, have real value. The key is extracting that value in a cost-effective way.

The Dupps family was involved in the development of rendering technologies almost from the very beginning. John J. Dupps joined Cincinnati Butcher’s Supply Co. at 15 years old in 1886 and quickly became the resident expert on the company’s line of rendering equipment. Over the ensuing years, he achieved the title of vice president, and his son, John J. Dupps Jr., later joined the same firm.

Rendering in those years was labor- and energy-intensive. Companies that did it relied on huge kettles that cooked the raw materials in hot liquids and on employees to skim the valuable byproducts off the top of the open vessels.

In the early 1920s, Myrick D. Harding of Armour & Co. in Chicago invented a dry-rendering process where the raw material was processed in a horizontal cylinder with an agitator, which was simultaneously heated by a steam jacket that encompassed the cylinder. The new process proved to be more energy-efficient than wet-rendering practices and easier to control.

Sensing an opportunity, the Dupps family founded the John J. Dupps Co. to refine and market the new rendering technology. It soon purchased a Germantown rendering facility to let food processors see the new process in action.

Figure 1

The banner at The Dupps Co., Germantown, Ohio, reminds workers that they have gone eight years without lost time caused by an accident on the job.

Over the years Dupps has evolved its product line, introducing some of the first continuous-rendering systems, which took raw product from storage bins and delivered finished product under the supervision of only a few workers, and adapting that same technology to work with poultry as the world altered its eating habits. The evolution continues even today as the company has worked to develop rendering systems for fishmeal and equipment to extract oil from soybean and other oil-laden seeds.

Dupps has expanded its reach in recent years to new international customers. This has kept the company’s 144 employees, about 60 percent of whom work in manufacturing operations, busy.

“We make bigger parts than most people,” said Jim Vose, the company’s human resources director.

Dupps has a machine shop where parts can be handled by individual equipment operators, but even in the machining area, cranes sometimes are used to feed parts into machines. The result of the machining and fabrication work are heavy-duty systems assembled in a dedicated area of the facility. These big projects have been a consistent sight on the Dupps shop floor, enough to keep two shifts working for the past several years.

It’s big work that calls not only for attention to work order details, but an awareness of how the work is done and the environment where the work is being done. Vose said the employees not only ensure that delivery dates are met and quality is maintained throughout the production process, but also that everyone leaves the job physically in the same way they started.

“The real main emphasis on our tremendous safety record is we push safety down to every single person on the shop floor,” he said. “It’s not the safety manager’s job. It’s not the supervisor’s job. It’s every employee’s job. They really take it to heart.”

Make Observations

Tom Weiss, Dupps’ manufacturing manager who has worked for the company for 36 years, said that the family-owned business has “never done anything that would jeopardize anyone’s safety.” Safety was always a concern at the company, he added, but it wasn’t until about 10 years ago that a formal program was put in place to institutionalize safety awareness. That’s when a former human resources manager introduced DuPont STOP® (Safety Training Observation Program) to Dupps.

STOP has been around for 30 years, and DuPont actually markets the program in several foreign languages and in distinct industries, such as oil and gas. It calls for the use of different tools and communication approaches to generate information and improve observational skills so employees display more willingness to work more safely and support ongoing safety efforts.

Weiss recalled that everyone in the shop was trained in what to look for and how to report it. Management then directed all supervisors to fill out at least two STOP cards per week, which was met with a little frustration at the time, but has now blossomed into one of the major safety tools in the Dupps organization.

Every week supervisors complete STOP cards that document both safe and unsafe practices, tools, equipment, or working conditions. All employees are encouraged to participate in this observation program, not just supervisors, and report their findings. An observation might be as obvious as a tear in an extension cord or as simple as a request to include part weight on a print so that a fabricator might not be tempted to pick up something that should be moved by a crane.

Figure 2

\The Dupps Co.’s David Dupps, senior vice president, and Tom Weiss, manufacturing manager (second and third from the left), accepted the 2015 Rusty Demeules Award for Safety Excellence from Jim Warren, FMA’s director of member services and education (left), and Frank Maccotan (right), director and industry leader, manufacturing, CNA, at the 2015 FMA Safety Conference in Plymouth, Minn., in late April.

And it’s not just unsafe situations that are noted. Weiss said many of the STOP cards recognize workers wearing the appropriate personal protective equipment.

If someone has a feeling that someone is watching them on the Dupps shop floor, the worker is probably correct.

“We don’t just talk the talk. We make everyone accountable for safety,” Vose said. “That helps to maintain that awareness. If you don’t maintain that awareness, that’s when things happen.”

Vose and Weiss review all STOP cards each week. The reviews reveal possible discussion topics that might be addressed during one-on-one conversations between supervisors and employees or in larger venues, such as the company president’s quarterly meeting with all employees.

Early success with the program resulted in years with no lost-time accidents, and since then employees have become acutely aware of Dupps’ overall safety performance.

“It’s been like a snowball where the employees have said that we have a great record here. We can’t get hurt,” Vose said.

Make It Visible

Dupps has everyday reminders that safety is a key metric for employees. (In fact, safety is one of the criteria in all employees’ performance evaulations.) If they show up to work with their minds clouded by family troubles or social obligations, these workers are reminded that they need to shift their thinking before beginning a shift.

Along with the large banner reminding the shop floor employees of the company’s safety streak (shown in Figure 1), Dupps also has an LED sign that updates workers on the no-lost-time tally. The safety accomplishments are covered in real time.

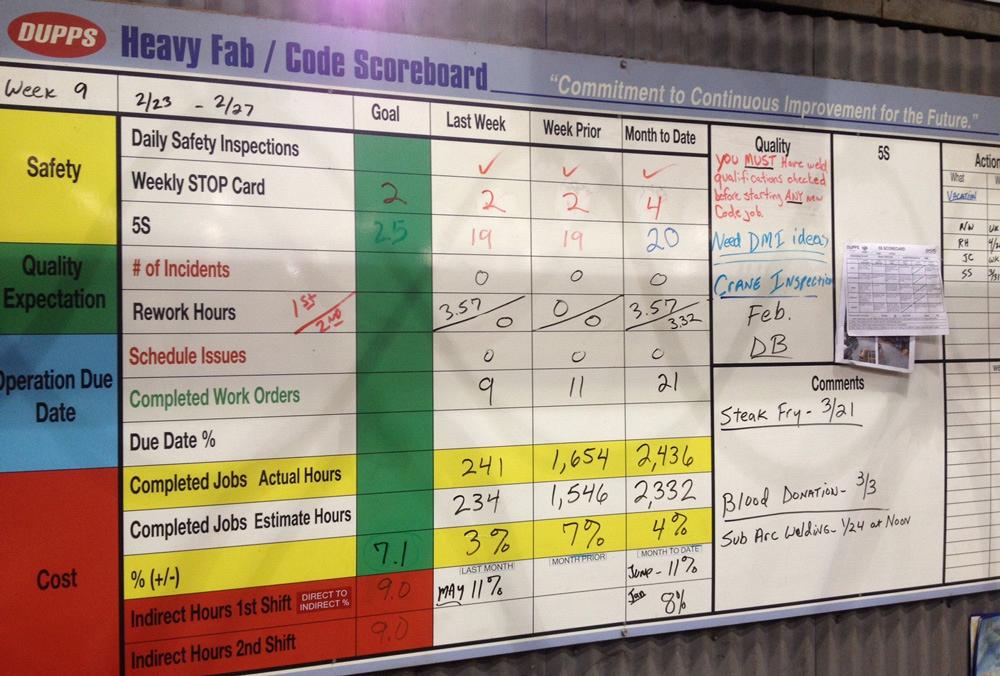

Additionally, a metrics scoreboard is prominently located on the shop floor (see Figure 3). Atop that scoreboard are safety-related topics, such as the daily safety inspections, weekly STOP card count, and a score for 5S (sort, set in order, shine, standardize, and sustain, all elements of a lean manufacturing technique meant to contribute to a clean and orderly work environment).

Finally, the unavoidable reminder comes. Before any employee can begin any task on a shift, he or she has to consult a simple checklist. It gets them to observe the work area, making sure that everything is in its rightful place and no safety hazards are immediately visible.

Figure 3

The Dupps metric scoreboard shows not only key information about safety, quality, productivity, and cost, but also reminders for other safety-related activities. In this case, workers are reminded about an upcoming crane inspection and the need for conversational topics for the weekly department metric improvement (DMI) meeting.

Most of the checklist items are general, but two to three are tailored to the particular manufacturing task. An employee typically runs through the checklist in 30 to 60 seconds, according to Vose.

“Keeping that level of awareness high is very important for us to have a good safety record,” Weiss said.

Make It Clean

Dupps is a practitioner of lean manufacturing techniques, and Weiss said he truly believes in the impact that 5S—which in the simplest terms is about a cleansing of a production floor—can have on a company.

“When you have a cleaner shop, you have a safer shop,” he said.

5S, which originated in Japan, stands for seiri, seiton, seiso, seiketsu, and shitsuke. As with most lean manufacturing, 5S is about eliminating waste and standardizing work. Seiri means to make work easier by sorting all of the elements of a work area eliminating items not needed. Seiton requires that the work area is set in order and is intelligently organized so that everything a person needs to do the job is there. Seiso calls for a clean workspace. Seiketsu mandates that standardized work instructions are created to ensure consistent results, no matter who might be doing the job. Shitsuke is sustaining the successful efforts through training and audits.

As an example of how 5S has changed the Dupps shop floor, Weiss recalled an area where skids were simply lying around, posing a trip hazard, and wooden 4-by-4s were haphazardly stacked against the wall. After a major cleanup, a staging area has been created for pallets, and racks have been built to hold the 4-by-4s. Nothing is lying on the ground anymore.

These 5S efforts are reinforced by periodic reviews in which sections of the manufacturing floor are judged on a 20-point scale, with 20 representing the top score.

“I think everyone is hitting their 20s most of the time,” Weiss said.

Vose said newly hired workers (who may have come from the stereotypical dark and dingy factory) really notice the results of 5S.

“We get new hires coming into the shop, and they can’t believe how clean and organized the shop is,” Vose said. “They just aren’t used to that.”

Makes for a Safe Future

It might come as a surprise to some that Dupps doesn’t have a designated safety manager anymore. The person who had that title retired, and the company doesn’t see a need to find someone to follow in his footsteps. Company management wants everyone to be responsible for safety.

Truthfully, a couple of individuals are responsible for coordinating safety meetings and the luncheon that celebrates another safe year, but those are more administrative efforts.

“Safety is not really one person’s responsibility. Everyone understands that safety is their responsibility,” Vose said.

The employees make it happen, and 2 million hours—and counting—prove that the approach works incredibly well.

The story behind the award

FMA’s annual Award for Safety Excellence, which is sponsored by CNA,is named after one of the organization’s most influential members over the past four decades. Rusty Demeules served as president of the FMA/CNA Safety Committee from its inception in 1989 until 1996, which just happened to follow the seven years he served on the FMA board of directors (1983 to 1989).

During his time on the Safety Committee, he helped to develop the FMA-sponsored insurance program, which is tailored for fabrication shops and tool- and diemaking companies.

Demeules worked in the fabricating industry for many years, starting with his family’s company,

Standard Iron and Wire Works, Monticello, Minn., as a machine operator in 1966. He worked his way up to become company president, serving in that role for 10 years before retiring in 1996.

That same year FMA honored Demeules with its Chairman’s Award for his service to the industry and the association.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI