Certified Public Accountants

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Saying “yes” to complex projects has benefits

The R&D Tax Credit is now permanent, which is good for metal fabricators

- By Bryan Elmore and Edward Dunn Jr.

- April 14, 2016

- Article

- Shop Management

Your company can be rewarded by saying “yes” to difficult projects.

On Dec. 16, the U.S. Congress announced the passage of the tax bill, Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015. This long-awaited tax legislation made permanent some important income tax deductions and credits related to businesses. One of the benefits made permanent was the research and development (R&D) tax credit. This credit rewards companies for time spent solving product and manufacturing problems.

The R&D tax credit originally was enacted in 1981 to encourage U.S. companies to improve their competitiveness. In 2001 President George W. Bush recognized that the credit was not being used because of the high innovation thresholds contained in the law. As a result, the R&D tax credit law was amended to lower the qualifying thresholds so that more companies could receive benefits.

The credit has had a bumpy ride since 1981. It expired after its initial four and a half years and was renewed on a year-by-year basis until December 2014. With the passage of the PATH Act, qualifying companies can rely on this benefit for many years.

The question now: What does it take to qualify?

Qualifications

When you think of R&D, your thoughts automatically turn to lab coats and scientists. That might have been the case in 1981, but it is no longer the standard.

To understand how a fabricator can qualify for the R&D tax credit, let’s consider a very familiar scenario. A customer presents a shop with a rough sketch of a part and asks the fabricator to accept the job. In this case, the fabricator has never made the part. The quantity, which could be one or 1 million, is irrelevant as it relates to the R&D tax credit.

The owner or the manager of the fab shop should consider these questions, which help to determine if the work associated with the new job might qualify for the tax credit:

- Is there uncertainty? This is a very broad requirement. Essentially, if the shop does not know how to make the part to begin with, it can claim a certain amount of uncertainty. This could involve working with a specific type of metal, difficulty in CNC programming, getting a specific design feature of the part to function properly, or manufacturing a part to the point where it can pass the customer’s quality specifications. It does not have to be new to the world; it just has to be new to the company.

- Is it technological in nature? The uncertainty involved in producing the parts must be concentrated in the manufacturing process. Employees in marketing, accounting, and executive management may be involved in some aspect of a new job or a product launch, but their time normally does not qualify for coverage under the R&D tax credit provisions.

- Is there a process of experimentation? Once a fabricator identifies the uncertainty, how is it overcome? This involves a trial-and-error process. For instance, after a CNC programmer is satisfied with a new part, a quality check may reveal that it doesn’t pass inspection, or the customer may find that it doesn’t meet its expectations for some reason. To produce an acceptable part, a part designer might have to revisit the design, and the CNC programmer might have to tackle the production process again. That’s the trial and error. Remember, a shop’s managers and employees have experiences and knowledge that are common to the industry, but they are applying this bank of knowledge to a specific part.

- What is the permitted purpose? The motivation for the process of experimentation must center around how the part functions, which is connected to the trial-and-error process used to determine the manufacturing process; improving the performance of the part, which most of the time is out of a shop’s control because it is the customer’s design; or reliability and quality (e.g., maybe the customer wants you to work with a new type of material).

A fab shop can meet this qualification even though the customer designed the part. When a fabricator quotes a part, it is not being paid directly for the development time associated with the part; a customer just wants the shop to produce the part that meets its specifications. The government, however, is interested in rewarding the fab shop’s risk with the tax credit. The idea is that the shop maintains more of its cash, which it can use to grow the business.

Qualifying Costs

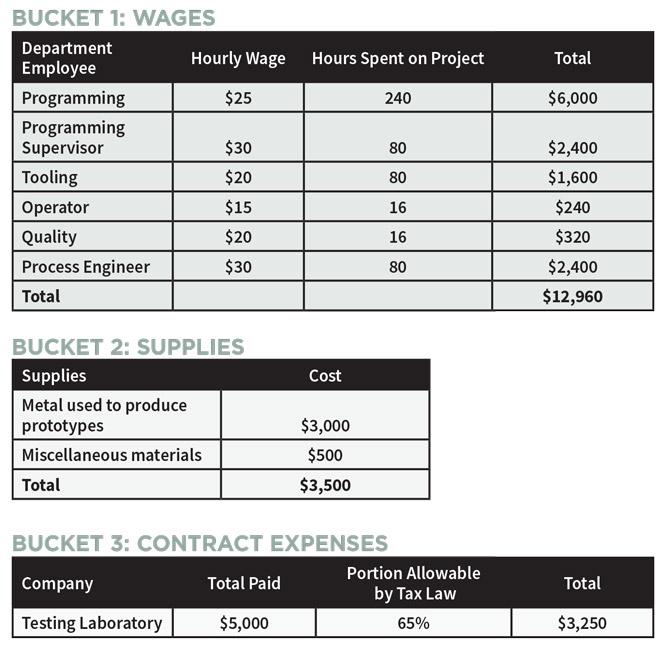

Once a fabricator can determine what activities might qualify for the R&D tax credit, it needs to know how to proceed. There are three buckets—or as the tax law calls them “qualified research expenditures”—that R&D costs can be put into: wages, supplies, and contract expenses. The expenses stop accumulating as soon as a part is ready for commercial production. In other words, when the first part has passed quality checks and the customer has accepted the part, the shop can no longer claim additional expenses and apply them to the tax credit.

Wages normally are the largest expense. It includes gross pay of the employees that spent time on the project, meeting the four tests previously mentioned. The expense is calculated by multiplying each employee’s gross pay rate by the hours spent on the R&D project. If the employee is salaried, then the company could use the percentage of total work time spent on the R&D project.

Supplies include the material used to produce prototypes or first articles. Typically, this includes the raw material, components, fasteners, and paint.

Contract expenses include any third-party testing or engineering services. There are two stipulations:

- The fabricating company must be financially responsible for the vendor’s results.

- Only 65 percent of the costs count toward the tax credit.

If a fabricator pays an engineering firm a fixed fee for its service, the IRS considers the engineering firm financially responsible, and the fabricator cannot include this cost in its R&D tax credit calculation. However, if a fabricator pays the firm on an hourly basis, then the fab shop is eligible to claim this cost. As a result, it is a good practice to tailor these agreements on an hourly basis with a cap. This ensures that a fabricator can include the costs in its R&D tax credit calculation and is protected from surprise charges.

In the Real World

To fully illustrate how the R&D tax credit can be applied in a manufacturing setting, let’s look at an example. A shop wins a job, and the customer sends it a model for an airplane part. This part requires a hinge that will be difficult to machine because of thickness specifications. (Keep in mind that the customer is not paying the shop to solve this machining problem; it just wants the shop to build the part.)

The qualified research expenditures might look like this:

That’s $19,710 that can be applied to the R&D tax credit. That shop would be doing itself a disservice by not exploring this cost-saving opportunity.

Is your shop missing out?

About the Authors

Edward Dunn Jr.

Certified Public Accountants

316-943-0286

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI