Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Driving change, not fork trucks

Quality Industries breaks revenue records in its quest to become a national player

- By Tim Heston

- May 28, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

Quality Industries has several customers that have been with the company for decades, including one in the recovery vehicle business. QI employees assemble aluminum components destined for a tow truck. Image courtesy of Quality Industries.

People not familiar with metal fabrication may view this industry as old, stodgy, stuck in the past, certainly not like any hot new tech start-up. What possibly can be new when it comes to making products of fabricated metal?

They should tour Quality Industries, a La Vergne, Tenn., fabricator that has been making parts for commercial trucks and recovery vehicles for decades. On the floor they’d see typical fabricated metal components and assemblies. But if they look closer, they’ll see the beginning of significant changes: a new emphasis on quality management, lean techniques, activity-based accounting, engineering and technical support, and improved information sharing and part flow.

Few top managers have been with the fabricator more than several years, and hearing them talk, you’d think you’re visiting a start-up, though one that just happens to have some decades-long customer relationships.

So what’s new about making products of fabricated metal? Quite a lot, actually.

President and CEO Warren Hayslip, who joined the company in 2013, put it this way: “Over the course of two years, we’ve gone from mediocre performance to the strongest financial results in the history of the company.”

The Current State

Bob and Georgianna Russell founded Quality Industries in 1972, and food service equipment and truck components were among the shop’s first product lines. Bob died about 20 years ago, but the Russell family still has a majority stake in the company. In 1984 QI moved into its current campus, with 267,000 square feet across two buildings, and in 2011 it opened a small assembly operation (less than 20,000 sq. ft.) in Denton, Texas, to serve one of its major trucking customers.

Other major clients include OEMs in the recovery and towing market (see Figure 1) and electrical distribution. Solar power has been a major growth area too. QI fabricates supports for solar panels, and it has shipped products all over the world.

Said Chris Fann, senior vice president of operations, “Products are mostly going out to the West Coast, Arizona, and southern Nevada, but we have sent products to Honduras and Brazil.”

As the new management team came onboard during the past two years, they arrived at an operation that, by metal fabrication industry standards, was quite large. It had long embraced technology: an automated storage and retrieval system, feeding several lasers and punch presses, remains a shop floor centerpiece. Besides fabrication, it also had significant stamping capabilities. Its core customers, especially those in the trucking and towing and recovery vehicle markets, have been with QI for decades. Yet its delivery performance suffered. As a result, the company board decided to bring in a new leadership team with the goal of improving performance in quality and delivery, increasing capacity, and broadening the customer base.

The new team valued machine technology investments, but they also valued the principles behind continuous improvement. Some managers came from upper-tier automotive suppliers, and many had managed high-product-mix environments—good experience for anyone leading QI, considering the nearly 8,000 SKUs the fabricator processes through its shop (though about 800 SKUs represent the majority of revenue).

Figure 2

These aluminum extrusions were bent on the company’s new rotary bending system. The extrusions will become the frames of sleeper boxes in commercial trucks.

They tackled the transformation in stages. They documented procedures and achieved ISO 9001 certification. They have undergone more than $16 million in new capital projects over the past three years, which is significant for a company with 2014 revenue of about $90 million. And they have initiated a lean transformation, engaging employees with idea-generation sessions, providing incentives, breaking old habits of overproduction, and improving part flow. The company has a long way to go, but leaders have big plans. They point to areas of the plant that will look completely different in the coming months and years.

What Costs What?

You can’t improve what you don’t measure, and when it comes to running a business, no measurement is more important than costs. “It was important to understand where we were in terms of profitability by customer and by product,” said Rick Marsh, CFO.

“We quickly dug in to try to understand where we were making money, and put away any misnomers.”

Part of the issue was in quoting and how the company applied burden rates—what Controller John French called a “peanut butter spread approach.” Essentially, the greater percentage of overall company revenue a job had, the greater its burden. Large jobs, such as those with sufficient volume for stamping, had significant burdens that made the work appear less profitable than it really was.

Accounting also used a prime margin approach, determined by subtracting prime costs (direct material and labor) from revenue. “So anything that came in that was carbon steel, and it ran across high technology, that often meant it didn’t have a lot of labor, so there wasn’t much to mark up,” French said. “Yet it was running across our most expensive pieces of equipment.”

To understand QI’s true costs, managers moved forward with activity-based accounting. As Marsh recalled, “We started to get into cost accounting profitability analysis [CAPA], where we started to understand the truth about where we were making money and where we weren’t.”

First they analyzed QI’s more than 100 work centers and aggregated them into 13 cost centers. “Then we thoughtfully went through the various nonproducing departments so we could understand how to allocate costs from each of those departments into our work centers,” Hayslip said. “Now, as we flow product through those cost centers, we have an intelligent understanding of what exactly our indirect costs are in addition to our direct costs. It was a revelation for us as a company to have that level of information, and it helped build a foundation for later transformation work.”

French summed it up this way: “The CAPA program was the first peg in truly understanding who we were.”

Technology Investment

With this information came a fresh perspective. Under the old assumptions about costs, many viewed the company’s higher-volume stamping work as less profitable than it really was. After all, some of the products it had been making hadn’t changed in a significant way for years. Changeover seemed to take forever, with fork trucks driving in and out of the area to exchange dies, and the shop’s stamping volumes weren’t immense. Wasn’t the future of manufacturing about being flexible? What could be more flexible than soft tooling, using lasers, punches, and press brakes?

Yet the CAPA program proved that stamping work was indeed profitable. In fact, a lot of it was QI’s bread and butter, components for commercial trucks and wreckers that it had made for decades. True, manufacturers need to be agile, but they have been agile using stamping presses for decades, going back to the Toyota Production System and single-minute exchange of dies.

Whence came the stamping department transformation, an early project for Vice President of Engineering Ken Ham. “We had 11 presses when I got here a year ago, and we pulled out three of them,” he said. “We had too many machines, and they were never running. We spent a lot of time on setup, and they used those extra machines as a security blanket.” Presses often were down for maintenance, and having extra machines on hand as backups made sense. “Now, though, we’re making [the presses] reliable,” Ham said. “When we’re done here, we’ll have only about five presses, but we’ll still end up with more capacity.”

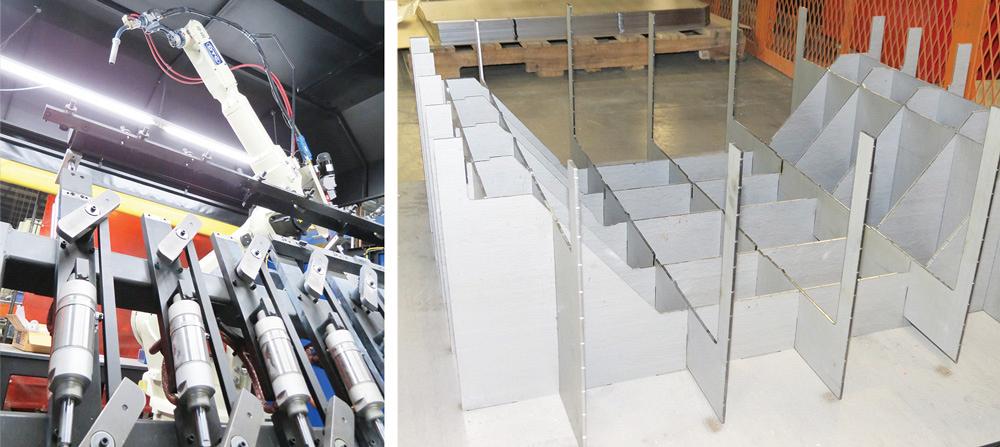

Figure 3

QI has expanded its robotic welding capability with a trunnion. The modular cell can be expanded with another trunnion on the other side. The company is testing laser-cut fixture designs (bottom), designed offline with software. Later this year it also plans to move away from the teach pendant and start programming welding routines offline.

At this writing, the company is completing a significant press rebuild, part of a broader program to update QI’s stamping technology. Already the company inspects punches and other elements of dies in new coordinate measurement machines (CMMs), moving closer to “first part good part” setups. Managers also plan to invest in die carts and institute quick-die-change technology and systems. In the department’s future state, presses will have standard hydraulic clamping and rails. Technicians will pull out dies, drive them to an adjacent area for inspection and preventive maintenance, and document it all to ensure that the next time the job comes up, the dies are in working order.

QI purchased a modern CNC vertical machining center to upgrade its tooling and fixture-building capability, as well as to machine components for its larger assemblies. And to supplement their current CMM capabilities and meet stringent quality requirements, which have increased in recent years, QI invested in a laser measurement arm, now used for inline inspection on the shop floor.

It also upgraded technology in its extrusion area. One major trucking customer contracts with QI to make sleeper boxes for trucks, and aluminum extrusions provide the frames (see Figure 2). Last year the company invested in a new CNC electric-hybrid rotary bending machine and fabricated custom tooling to handle extrusions. It’s also rebuilding an older bender, and together those two systems replace numerous older machines.

In the forming department, many noticed that a lot of large press brakes were being used to form some rather small parts. “We segregated parts by size and tonnage, and found that about 10,000 hours’ worth of press brake work were for parts that are 4 feet or less and required less than 50 tons [of forming tonnage],” Ham said. “And yet our smallest brake was 130 tons with an 8-ft. bed.”

As Terry Tidwell, vice president of business development, put it, “We were using a dump truck to carry a shovelful.”

The company bought an electric press brake to handle those parts. Thanks to increased speed and efficiency of the electric brake’s ram, forming throughput is on the way up.

QI also is expanding its robotic welding. As a recent improvement, engineers redesigned a fixture so it could accept more variations in a product family. It’s also testing laser-cut fixtures, designed off-line using software that mates flat laser-cut pieces with other standard clamping elements, shortening fixture development time dramatically. Engineers also hope to start programming the robot offline (see Figure 3) within the coming months.

At the west end of the main plant is the centerpiece of all the capital investments over recent years: an automated powder coating line, complete with a six-stage pretreatment system; 10-minute color change with powder reclamation; and filtration technology that neutralizes hazardous chemicals, so waste from the system can safely flow down the drain (see Figure 4).

“It has all the bells and whistles,” said Fann. “It has a system in the paint booth where it scans parts coming in and performs an automatic adjustment on the gun position, so you don’t waste as much powder.”

The company decided to place the new coating system at the west end of the shop. They did this for a good reason, and it has to do with fork trucks—or, more precisely, the elimination thereof.

Figure 4

QI’s new powder coating line comes complete with a six-stage pretreatment system; 10-minute color change with powder reclamation; and filtration technology that neutralizes hazardous chemicals, so waste can safely flow down the drain. Photo courtesy of Quality Industries.

“Over the course of two years, we’ve gone from mediocre performance to the strongest financial results in the history of the company.”

—Warren Hayslip, Quality Industries

June15FAB_

Better Flow

Over two days last year a team analyzed just how the company used its fork trucks—all 48 of them. They extrapolated the data and found that people were driving fork trucks between 90,000 and 100,000 miles a year, and almost half the time the trucks were empty, being driven back after delivering tools and materials.

The trucks had a lot of miles on them simply because, as is common in many shops, processes were scattered. For instance, some parts were punched and bent in the main facility, traveled to the adjacent facility for assembly, then came back to the main facility for painting. That makes for quite the tangled spaghetti diagram.

In the year since, the company has gotten rid of 13 fork trucks, mainly by moving processes like assembly. Transportation time has been reduced by 70 percent for one product family, just by moving assembly closer to the upstream processes in the main facility. The flow isn’t perfect—some parts still come from the adjacent building—but it’s certainly an improvement.

To improve matters further, the company is looking to its Texas facility, now a small assembly operation that builds sleeper enclosures for commercial trucks. Although that line produces only about five major models, they can be customized dozens of different ways. Most products are somewhat standard, but a portion of the assembly includes components that go on only certain model iterations. Right now these components sit in inventory so that the Denton facility can respond to customer demand, but soon the company hopes to reduce that inventory significantly.

QI’s Texas operation will soon get a lot more room. The company plans to move to an 86,000-sq.-ft. facility in Denton, which will house not just assembly but also fabrication, giving QI room to expand more in the south-central U.S. market. Managers plan to move several punch presses and brakes down to Texas, and to set up the new operation with optimal product flow in mind (see Figure 5). The goal is for components to be punched, bent, and delivered in kits to assembly. It’s a classic pull system triggered by customer demand, with enough of an inventory buffer to handle process variation—but no more.

All this will open up more space on the Tennessee campus, where in the press brake department you can see a glimpse of the future. There a monitor shows a scheduling dashboard, continually updated, displaying which jobs are coming next (see Figure 6).

No longer do operators produce a week’s worth of material for a job, an element of traditional batch-and-queue flow and a big symptom of overproduction. The goal is for operators to produce just what’s needed to satisfy the “internal customers” at downstream processes (see Figure 7).

In the future state, with the spaghetti diagram untangled, workers will see plainly where work is coming from and where it’s going, arriving and leaving in small lot sizes on rolling carts. The main plant has three anchors: stamping presses to the east; the punching and laser cutting system with automatic storage and retrieval (what Ham called “the heartbeat of the operation”) in the middle (see Figure 8); and the automated powder coating line to the west. When possible, parts will travel linearly from the punches and lasers to the press brakes. From there part flow will split, with some products traveling to welding and other products heading straight for powder coating. All this means fewer hours behind the wheel of a fork truck.

Design Initiatives

QI has worked with customers to change designs in the past. For one OEM of recovery and towing equipment, staff worked to change an all-steel design to an aluminum one that was lightweight and corrosion-resistant. But all this was customer-driven, and it certainly wasn’t a core competency that the fabricator sold.

This began to change a little more than a year ago when QI began adding to its engineering staff and offering not just standard design assistance and design for manufacturability, but also product development from the ground up—and a few assembly areas on the floor are the fruition of this effort. The customer came to QI basically with an idea, and the engineering group took it from there.

Figure 5

This punch press, with a brush table that doesn’t mar the thin prepainted sheet metal destined for the commercial truck sleeper box, is destined for Texas, where QI plans to expand significantly.

QI will continue on as a contract manufacturer, of course, but as Hayslip explained, the design element should help strengthen customer loyalty and help the company grow with customers—offering fabricating for the prototyping and early in the product life cycle, then stamping if the product becomes successful and volumes grow (and if component geometry is conducive to stamping, of course).

“We’re in this together,” Hayslip said.

“In this together” pretty much sums up QI’s growth strategy in its quest to grow from a regional into a national and global player. At this writing, the organization expects revenue to end the year well over $100 million, a record for the company. Apparently, the growth strategy is working.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI