Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fabricating with purpose

Missouri fabricator fosters employee engagement

- By Tim Heston

- January 10, 2013

- Article

- Shop Management

Cambridge Engineering’s punch press performs in- process tapping, which eliminates the need for the secondary process.

The flood of 1993 changed everything at Cambridge Engineering. Managers at the manufacturer of commercial heating and air movement systems were told that the levy on the Missouri River, near Chesterfield Mo., just west of St. Louis, wouldn’t break. But it did break, the shop flooded, and the manufacturer had no choice but to buy new CNC machines.

“It was at that time we were introduced to what new CNC machines could offer, and the importance of quick setup and changeover.”

So said Mike Mueller, vice president of manufacturing, talking in late October with a group of visiting fabricators who were part of LeanFab Workshop & Tours, a lean manufacturing conference focused on the high-mix, low-volume shop and organized by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association Intl.

The flood was a turning point for Cambridge. During the ensuing years the company gradually transitioned away from traditional batch-style production toward single-piece part flow, with all components needed for one product moving in kits to processes downstream.

In the middle of this came the Great Recession. The downturn affected commercial construction dramatically, and Cambridge saw its sales plummet by more than 50 percent. Sustaining sales through tough times were newly launched products in other markets, leveraging the company’s core technology and applying it to other sectors.

Still, managers knew things had to change. At the time the company’s average annual employee turnover was 80 percent. High turnover isn’t that uncommon in businesses tied to commercial construction. Cambridge’s busy time occurs during the last five months of the year, and so it would hire temporary workers for those months. “We essentially were throwing labor at the problem,” Mueller said.

But such high turnover makes it tough to develop collaboration, teamwork, and a good corporate culture. After all, it’s tough to develop good working relationships if most of your co-workers will be gone soon.

Today, even though demand remains highly cyclical, average turnover has plummeted to about 5 percent a year. How? As Bruce Kisslinger explained, it took a lot more than preaching the virtues of lean and single-piece part flow. In fact, the title on his business card says it all: Vice President of Quality, Keeper of the Corporate Culture.

Kisslinger should know all about his company’s culture; he’s worked there more than 40 years. When he arrived, the shop floor had typical manual equipment of the day, like mechanical leaf brakes with foot pedals and manual lever punches. But he remembers the racks most of all—so many racks. Material handlers scurried around the floor all day, looking for and retrieving parts, then carrying proc-essed parts back to yet another rack. It was classic batch-style processing. It could take 12 weeks or longer to produce one unit. Meanwhile, piles of work-in-process tied up cash and wreaked havoc on the balance sheet.

Today workers at Cambridge Engineering produce three times more annually than they did 10 years ago, and they do it in a smaller facility. Lead-times also have shortened by 75 percent. How did they do it? Many elements factor into the equation, but Mueller pointed out the common thread: “Somebody who’s engaged [in their work] is worth two to three times those people who aren’t engaged.”

Figure 1: At the Education Station, workers place defective parts so that they can analyze the problem, educate each other, and learn from the error.

To that end, managers and front-line workers together help develop and continually improve employee engagement. It all boils down to two words, really: People care.

A Different CPI

Core to such engagement is CPI. This has nothing to do with consumer prices; at Cambridge it stands for continuous process improvement. The company has several CPI teams that focus on certain areas of the business and shop floor. These teams are contagious. For instance, after the sheet metal CPI team began meeting regularly, engineers and designers began to see how communication and quality improved. Soon engineers developed their own team.

“Who facilitates these teams? It really could be anybody,” Kisslinger said. “It doesn’t have to be someone from the office. For instance, a design technician in the engineering department had a passion for these improvement concepts. He’s not an engineer, but he facilitates that team.”

Here that positive employee engagement germinates. Multiple teams collaborate with each other as well, fostering teamwork across the organization.

Communication Is Paramount

Rob Huddleston, a technician in the company’s prebuild department, which handles fastening and spot welding of subassemblies, pointed to one of the company’s latest heating units. At first glance it doesn’t look like anything out of the ordinary, but a closer look would impress anyone who works with sheet metal. Most portions of the product require no welding. In fact, all weld seams were replaced by either a bend or fastener.

This engineering change has had dramatic effects on productivity, product quality, and process reliability. Not only do these products require little if any welding, but they also are easier to repair if mistakes do occur.

Say a part is formed incorrectly in the press brake. That formed part gets welded to another component, then another. Then an operator at the spot welding station notices that the part won’t fit to the larger subassembly. So the component has to be ground off and repaired, or scrapped altogether. “We had to turn into a kind of body-shop worker to make everything look like the mistake never happened,” Huddleston. “Now mistakes are much easier to correct,” he said. “They don’t happen often, but we are human, after all.”

Scott Moore, a machine operator in the fabrication department, pointed to a table that’s the result of an idea that embraces this human trait: the “Education Station” (see Figure 1). During the LeanFab conference visit, the table had a part with a flanged frame that didn’t fit properly with mating components. Moore asked, “Is this a fabrication problem? An engineering problem? Why is this part wrong? That’s what this table is all about. This is where we all put our heads together.

“People don’t want to admit that they make mistakes, of course,” Moore continued. “What the Education Station has done is change the perception. Mistakes aren’t a problem. They’re an opportunity. We want people to know it’s OK to admit you messed up, because chances are if you messed up, somebody else will do the same thing.”

This allows everyone to document and learn from mistakes and, if needed, change procedures. In fact, all shop floor procedures are clearly documented within each department. Laminated binders in plain view serve as a general reference, with large photos and illustrations taking workers through each stage of the process. This helps bring new workers up to speed quickly. Workers also happen to be cross-trained regularly, and clear documentation helps here as well.

Figure 7: Final assembly workers produce eight units a day. After significant 5S efforts, stations have been organized, and tools can be seen on boards, not buried in individual toolboxes.

About Flow

Cambridge does have standard product lines, but these can be highly customized to fit a customer’s building or application. That’s why the fabricator has embraced certain elements of traditional lean manufacturing and adapted them to fit its high-mix operation. This includes single-piece part flow. Every product may be different, but workers make sure each product travels from one process to the next with all of its components; no more must final assemblers scurry around the floor to find a missing part.

The company’s punch press and laser marks each part in-process. The TRUMPF punch press also performs in-process tapping as well as forming, for offsets and flanges, eliminating secondary processes. Which machine to use—the laser or punch—depends on the schedule, as well as machine capacity and capability. Moore pointed to a tight grating, or screen, of small diamonds (see Figure 2).

“The punch can process this screen probably five times faster than the laser,” Moore said.

Parts are fabricated in kits, which start at the punching machine and laser. The company typically cuts all parts required to produce four products. A cart with four products’ worth of components then goes to press brakes for forming.

After bending, the brake operator places these formed parts in four different compartments on another cart. Each compartment has a full set of parts required to build one heater. The cart (now with four formed kits) then is rolled to the next process. From there all the way to shipping, every component needed for an assembly flows together from one manufacturing process to the next (see Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5).

About a decade ago, during those batch-processing days, managers decided to install a conveyor along the length of the prebuild area. Workers would spot weld all parts needed for a batch of, say, 20 units, send down all of one part needed for the entire batch, then all of a next, and so on.

This batch-style part flow caused operators to spend much of their days moving up and down the conveyor, searching for and retrieving the parts they needed. Now all parts needed for one subassembly are sent down the conveyor (see Figure 6) in a group, so technicians receive all the parts they need immediately.

Have Some “Takt”

Although Cambridge is a high-product-mix operation, it does abide by the principles of takt time, a drumbeat that matches the pace of manufacturing with customer demand, whether that demand is internal (downstream operations) or external.

Cambridge’s final assembly workers strive to produce one unit every hour (that is, one-hour takt time), with the goal of eight units a day—and all workers upstream feed them the parts at the right time so that they can accomplish this.

They work 10-hour days and get a half-hour lunch. This leaves an hour-and-a-half buffer, which is needed because every unit may be different. Some units may take more than an hour to assemble, some units take less. If workers have extra time at the end of the day, they can spend it on improvement projects (see Figure 7 and Figure 8).

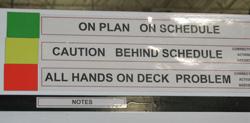

Figure 9: This legend for the company’s central information board describes the simple color coding used to show the status of a job or task. This not only includes jobs, but also periodic training events.

Cambridge experiences high variability not only in product mix, but also in demand. To deal with this, the company has flexible work hours. During the slow months, employees may work four 10-hour days, then work either four or five 10-hour days during the busy months, depending on the demand level. If times are extremely slow, as they were during the past recession, hours may be reduced to three or four eight-hour shifts.

Such varying demand is also the reason for a buffer of WIP adjacent to final assembly—an area of stacked sheet metal shells. These shells are produced to a sales forecast, but they are standard enclosures in which assemblers can insert a wide variety of internal components. The controlled WIP buffer ensures that workers in final assembly can produce all they can during the busy times. At the end of the busy season in December, that WIP buffer is depleted.

Optimal throughput is paramount during the last five months of the calendar, because that’s when most revenue for the year is made. Once a burden, the cyclical demand now is a blessing of sorts. The first few months of the year may be slow, but this is when CPI teams switch into high gear. Slow times allow people to regroup, analyze, and improve.

About People

Eyeing Moore, the sheet metal machine operator, Kisslinger made a pronouncement. “Is anyone going to be around December eighth? If you’re in the area, we’re going to have breakfast with Santa!”

Moore shook his head and smiled. “Yeah, I got roped into it.” Laughter all around.

Introducing the group to Rob Huddleston, the prebuild department technician, Kisslinger didn’t spout out his resumé—how many years the technician had been with the company, and so on. Instead, he talked about canoeing. “Does anyone here do canoeing? If so, you’ve got to talk to this guy!”

Corporate culture historically has involved, at least in some fashion, an “us versus them” mentality—be it this department versus that department, engineering versus manufacturing, or managers versus workers. According to both managers and workers at Cambridge, the company has worked past this mentality. Engineering works with manufacturing. The sheet metal department works with painting and final assembly. The idea is that everyone is on the same page, and no one should be working to the detriment of anyone else. At Cambridge, it seems, there are no fiefdoms.

Collaboration fostered by the CPI teams helped overcome this. So have efforts like the Education Station and other visual management strategies (see Figure 9). For instance, a central board on the shop floor shows every job in process, and certain colors indicate their status. With a quick glance, every worker knows where every job stands.

But more than anything, perhaps, is that the 100 employees of Cambridge Engineering treat each other as, well, people. The roster includes many fathers and sons as well as mothers and daughters. The manufacturer is like a family business, just with many families.

Continuous improvement can help make a great manufacturing company, but at Cambridge it has also helped build a better working community. Instead of spending all their time putting out fires, managers and employees have at least a little more time to talk to each other about what makes life fun—like canoeing trips and Santa Claus.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI