Associate

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Hourly or Salaried? Exempt versus nonexempt employees in metal fabrication

4.2 million workers added to the list of nonexempt employees entitled to overtime

- By Dannah Rodriguez and Jonathan Martin

- October 27, 2016

- Article

- Shop Management

While fabrication shop owners are busy keeping abreast of the latest trends in the industry and trying to remain profitable in the wake of increasing costs and competition, another threat to their business remains largely ignored. Effective Dec. 1, 2016, 4.2 million employees will be entitled to overtime wages.

The Labor Department estimates that several hundred thousand workers in over 60,000 primary metals and fabricated metal products companies will be affected by the updated salary levels. This will cost employers millions of dollars to pay for employee overtime wages.

In the manufacturing industry, the Labor Department estimates that the new regulations will cost employers over $150 million in 2017 alone. These numbers demonstrate how even typically “blue-collar” industries are greatly affected by the updates to the “white-collar” exemptions.

Do you know which of your employees will be affected by this regulatory change? Do you have a plan to address compliance with the law? If you are like most fabrication employers, the answer is probably no.

The Fair Labor Standards Act

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) is probably the least understood, and consequently most violated, of all federal labor and employment law. In a nutshell, the FLSA establishes minimum wage, overtime pay, and recordkeeping standards for most private sector businesses. Covered nonexempt workers are entitled to a federal minimum wage of not less than $7.25 per hour (though this is subject to state laws that require more), and they are entitled to overtime pay. Overtime must be paid at a rate not less than 1.5 times the employee’s regular rate of pay for all hours over 40 that are worked in a workweek.

The FLSA is enforced by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division, but employees have a private cause of action as well. Employees who are incorrectly paid are entitled to an amount equal to the underpayment as statutory “liquidated” damages, and an employee that prevails at trial is entitled to attorney’s fees.

Exempt Versus Nonexempt Employees

Most workers are classified as either exempt or nonexempt, depending on their salary and the type of work they do. Exempt employees are not entitled to overtime pay, while nonexempt employees are. The most common exemptions are referred to as the “white-collar exemptions.” These apply to certain administrative, executive, and professional employees; computer professionals; and outside sales employees.

The primary advantage of classifying employees as exempt is that you do not have to track their hours of work or pay them overtime, no matter how many hours they work. This is obviously appealing to employers. The exemptions are just that—exceptions to the rule. They are very narrowly construed, and the employer always bears the burden of proving that a worker is correctly classified as exempt. As a result, it is important to understand the strict requirements of the narrow rules.

For an employee to be categorized as exempt under the FLSA, there are three strict requirements. First, an employee must be paid on a salary basis. This means that they are paid the same amount each week, and their pay is not subject to reduction based on quality or quantity of work. This also means that the employer is not allowed to deduct pay when no work is available or if the employee works less than eight hours in a regular workday.

The only time that an employer is allowed to deduct from pay is when the employee is absent for one full day or more for personal reasons, other than sickness or disability. If the employee is out for a sickness or disability, then the employer is allowed to deduct based on a bona fide plan providing compensation for loss of salary occasioned by sickness or disability and is not required to continue pay past the days or weeks allowed to be missed based on the plan.

However, it is important to understand that the employee must perform no productive work during the absence. In an era of smartphones and constant business communication, this is a difficult burden to meet. As a result, it is generally unwise to make deductions from a salaried, exempt employee’s pay.

Second, effective Dec. 1, 2016, the salary must meet the minimum level of $913 per week or $47,476 per year. This is a significant increase from the current level of $455 per week. Up to 10 percent of this salary requirement can be satisfied by nondiscretionary bonuses, incentives, and commissions that are paid quarterly or more frequently. Every three years, beginning in January 2020, this number will increase to keep up with inflation. However, a salary at a certain level is only the beginning of the analysis.

Third, the exempt employee must meet certain primary duties that are unique to each exemption. For the professional exemption, employees must primarily perform work that either requires advanced knowledge in a field of science or learning (usually obtained through a degree) or that requires invention, imagination, originality, or talent in a recognized field of artistic or creative endeavor. The professional exemption includes employees such as learned professionals, creative professionals, teachers, and employees practicing law or medicine.

The administrative exemption includes employees who perform nonmanual work directly related to the management or general business operations of the employer or the employer’s customers. Critically, the employee’s primary duty must include the exercise of “discretion and independent judgment” with respect to matters of significance.

Factors to consider when determining if employees are exercising discretion and independent judgment include authority to commit the employer in matters that have significant financial impact or deviate from established policies and procedures without prior approval; authority to negotiate and bind the company on significant matters or provide consultation or expert advice to management; involvement in planning long- or short-term business objectives; and authority to investigate and resolve matters of significance on behalf of management.

The executive exemption applies to employees who have the primary duty of managing the enterprise or managing a customarily recognized department or subdivision of the enterprise. To qualify for the executive exemption, employees must regularly direct the work of at least two other full-time employees and have either the authority to hire or fire other employees, or the employee’s suggestions as to the hiring, firing, or change of status of other employees is given particular weight.

For the primary duty to be considered management, employees’ activities must include interviewing, selecting, and training; setting pay and hours; directing other employees’ work; maintaining production or sales records for use in supervision of other employees; appraising employees’ productivity for promotion recommendations; disciplining; determining and ordering materials or supplies; controlling the flow of distribution material; planning the budget; or monitoring safety and legal compliance measures.

As a general rule, employees must spend more than 50 percent of their time engaged in management activities for it to be considered their “primary duty.”

Highly Compensated Employees

In addition to the professional, administrative, and executive exemptions, the regulations also allow a special exception for “highly compensated” workers that loosens the strict restrictions. Beginning on Dec. 1, 2016, highly compensated employees are exempt if: (1) they earn $134,004; (2) their primary duty includes performing office or nonmanual work; and (3) they regularly perform at least one of the exempt duties or responsibilities of an exempt executive, administrative, or professional employee.

Common Mistakes

Misclassification. The most common FLSA mistake is classifying all “salaried” employees as exempt. Salary is only part of the requirement. If the employee fails to meet the duties test, he or she is nevertheless entitled to overtime.

Furthermore, an employee’s job title is irrelevant. Only the actual duties count. Accordingly, the only way to determine if an employee is exempt is to do an in-depth analysis of whether their job responsibilities and salary fit into one of the allowed exempt categories under the regulations.

One common misclassification is for secretaries and professional assistants. The Labor Department has specifically stated that administrative tasks that involve applying well-established techniques, procedures, or specific standards; clerical or secretarial work; recording or tabulating data; and performing mechanical, repetitive, recurrent, or routine work are not exempt. So, typical front-office staff, including secretaries and assistants, do not qualify as exempt even if their salary is above the current, or future, salary threshold.

Another common misclassification is supervisors or first-line managers. Many employers think that all supervisor- or management-type positions are automatically exempt. Recently Walmart learned differently, paying a $4.8 million settlement for mistakenly classifying vision center managers as exempt. Whether a supervisor or manager is exempt depends on the specific job duties of that particular supervisor or manager.

Office staff, supervisors, and managers are not the only types of misclassified employees. Recently a court specifically addressed whether a CAD detailing and drawing position was exempt. While the specific facts of each case are determinative, in this case, the CAD operators were deemed nonexempt, and thus entitled to overtime.

Miscalculation of Overtime Rate. A second major mistake by employers is miscalculating the correct rate of pay for overtime wages. The regulations provide that employees must be paid 1.5 times the “regular” rate of pay.

Many employers confuse this with the employee’s “hourly” rate of pay. The “regular” rate is defined as all forms of compensation divided by hours worked. Accordingly, the “regular” rate includes any bonuses, commissions, shift differentials, and other forms of compensation.

Failure to Keep Adequate Records or Track Employee Working Time. A third mistake is failing to keep up with hours employees are at work. If nonexempt employees come in a few minutes early or leave a few minutes late, they may be entitled to be paid for that time. Also, employees who eat lunch at their desk may be entitled to be paid for their lunch. For an employer to deduct a lunch shift from employees’ time, an employer must give the employee at least 30 uninterrupted work minutes away.Practically, it is difficult for employees to remain uninterrupted when eating at their desk. An employer is not immune to liability because the employee does not follow a strict schedule. The employer must keep records of the time employees are at work to properly compensate them. As a result, it is important for supervisors to monitor when employees clock in and clock out. Supervisors should also ensure that meal periods are uninterrupted.

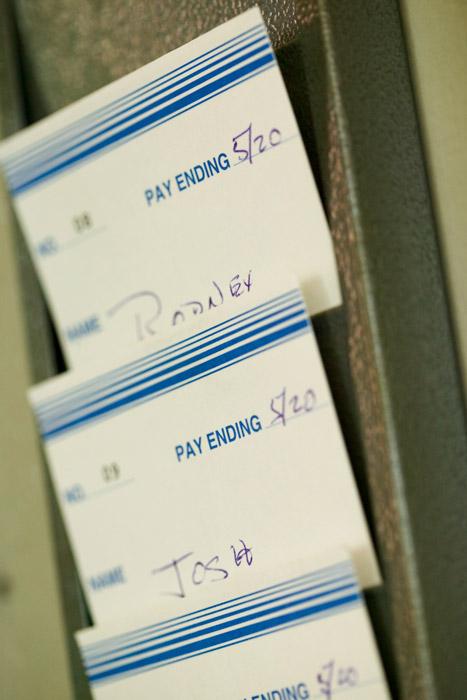

The regulations also impose an affirmative duty on employers to keep records on wages and hours of all employees. As part of these records, the employer must keep the number of hours worked in each workday and total number of hours worked each workweek. There is some flexibility in the rules, because an employer is allowed to choose its own recordkeeping method; a time clock for all employees is not required.

Costly Errors

Walmart is not the only victim to FLSA noncompliance. Since 2009, nearly $1.6 billion has been recovered for back wages by the Wage and Hour Division of the DOL. What is more frightening than the incredible size of this amount is that it does not include any other costs associated with the claims filed. When a violation has occurred, the employer must not only pay for back wages, but also may have to pay double the amount of back wages as liquidated damages (damages that are meant to penalize the employer). Also, the employer must pay for the plaintiff’s attorney’s fees and court costs.

So even a small mistake on the employer’s part by not paying for a few hours of overtime can quickly turn into an expensive litigation or settlement bill. Large recent settlements include a $90 million settlement from Farmers Insurance to claims adjusters; a $29.9 million settlement from RadioShack to store managers; an $18 million settlement from UPS to part-time supervisors; and a $9 million settlement from Taco Bell to managers and assistant managers.

How to Avoid Exposure to Potential Liability

Wage and hour class actions have exploded in recent years, and the trial attorneys are always on the lookout for a new target. The pending changes in the law will make that quest even easier.

The best defense is a good offense. While many bemoan the Dec. 1 changes, we suggest businesses use this as an opportunity to re-evaluate their compensation model and employee classifications.

Audit all job categories to address misclassifications. Also, be sure to document changes, and clearly communicate to employees that off-the-clock work is unacceptable. Have a reporting mechanism for bringing underpayments to management’s attention.

Train managers and supervisors on their requirements under the Fair Labor Standards Act. And because the FLSA involves complex regulatory and statutory provisions, use expert consultants and attorneys to ensure compliance.

Finally, do not allow wage and hour complaints from employees to go unattended. Address each and every concern. Communicate findings from the investigation back to the employees to show them that you take wage and hour complaints seriously.

About the Authors

Jonathan Martin

Equity Partner

478-621-2407

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI