Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How SWOT and lean go together

Good planning should be grounded in real data, not assumptions

- By Tim Heston

- November 5, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

When managers plan, they plan to be successful. To that end, they turn to various tools, one of them being the tried-and-true SWOT analysis, which covers strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. That’s all well and good, but how exactly do you define a company’s strengths and weaknesses?

Shahrukh Irani and David Lechleitner are tackling this challenge. Irani is president of Sugar Land, Texas-based Lean & Flexible LLC, a consultancy, and Lechleitner is principal, cloud solutions, for Exact Online, Waltham, Mass. At FABTECH® in Chicago this month, the two will collaborate on a presentation about two improvement tools—SWOT and flow assessment—and how they complement one another. Irani uses flow assessment as part of his Jobshop Lean approach, using his firm’s PFAST package, or the Production Flow Analysis and Simplification Toolkit.

“It all really starts with understanding who you are today, but also understanding where you want to go,” Lechleitner said. “One of the tools is to develop a three-year plan, and one of the elements of that is the SWOT analysis. This doesn’t need to be a drawn-out process. You can do it relatively quickly. And it doesn’t have to be part of a three-year plan, either. It could be a one- or two-year plan, simply because things are changing so quickly.”

As the two explained, using both SWOT and flow assessment helps everyone keep one eye on shop floor realities and another eye on a broader, though still realistic, vision for the future.

As Lechleitner explained, “The flow assessment complements the SWOT analysis. It starts with SWOT, and the flow assessment is a component of determining those internal strengths and weaknesses.”

Defining Strengths and Weaknesses

Internally, managers may confuse the company’s perceived strengths with where they think industry is headed. For instance, say a shop feels that its stamping operations really aren’t in the company’s future. After all, the future is all about low volumes and adapting to new part designs, perfect for the soft tools of lasers, plasma cutters, turret punch presses, press brakes, panel benders, and folding machines—right?

But after some analysis, the shop finds that some part designs have indeed not changed for years, and they aren’t likely to change much in the future. These jobs not only represent a large amount of revenue, but they’re actually very profitable. Maybe stamping is in the company’s future after all?

This story resembles one managers at La Vergne, Tenn.-based Quality Industries told earlier this year (see “Driving change, not fork trucks,” available at thefabricator.com). The example illustrates the need for a clear, objective view of the current state of affairs.

This is where flow assessment comes into play. Irani adapts this process, the PQR$T Analysis, for high-mix, low-volume operations. It considers the reality all job shops face: They manufacture diverse products (P) with different routings (R) produced in varying quantities (Q) representing various amounts of revenue and margins ($), as well as different demand cycles (T).

Performing such an analysis, Irani said, avoids pitfalls that many job shops fall into, particularly when implementing improvement projects. “One pitfall includes a lack of complete understanding of the current state,” he said. “Does a shop understand the different product families in their product mix?

Are they strong or weak in their performance, quality, cost, and delivery when fulfilling orders for each of these? Shops do not spend time identifying their product families.”

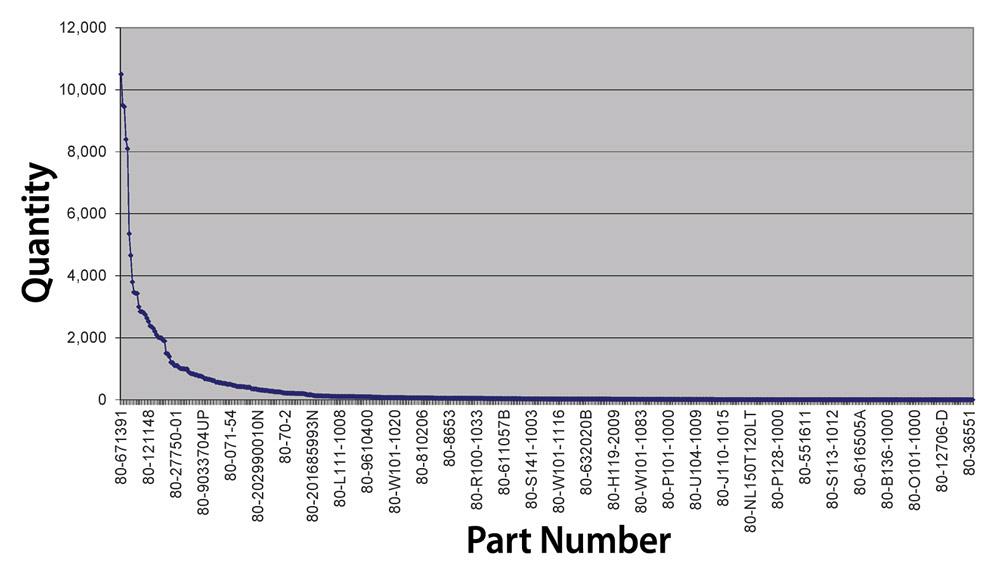

Figure 1

This shows a typical product-quantity analysis for a job shop. A few high-quantity jobs are accompanied by a long tail of short-run products.

By “product families” he’s not referring only to product families from a certain customer, but also jobs from different customers and even different industries that happen to share similar manufacturing characteristics, such as similar part geometries, routings, production quantities, or demand cycles.

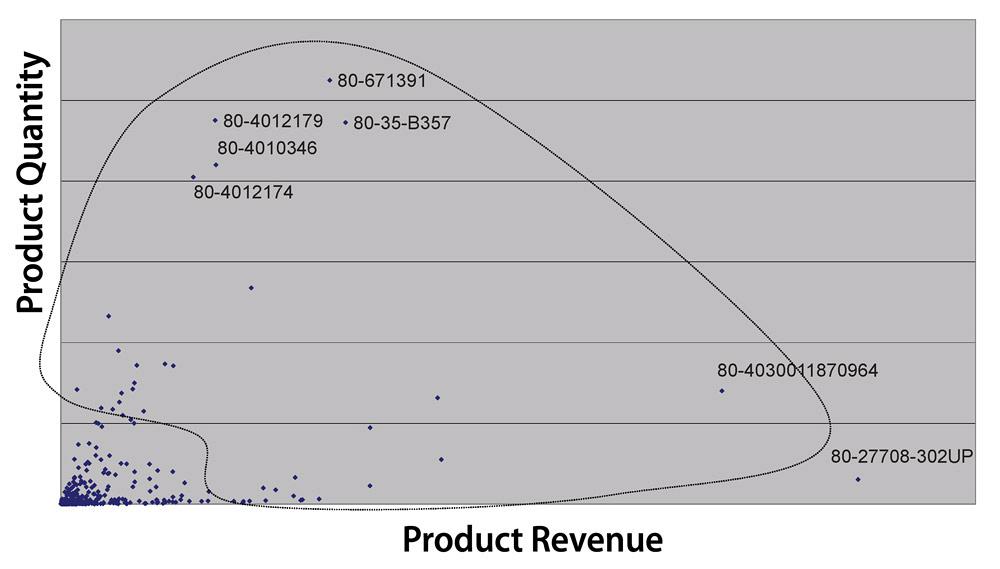

Most job shops have relatively few part numbers ordered in high quantities and a “long tail” of smaller jobs (see Figure 1). The big jobs involve a lot of metal parts, but metal parts don’t make payroll. Revenue does, and when shops correlate revenue with part volumes, they often don’t find the same long tail shape (see Figure 2). Some low-quantity parts may still bring in significant cash, sometimes more revenue than a high-volume job. This data, Irani said, shouldn’t be ignored.

As Irani put it, “Job shops should focus on being really good when it comes to fulfilling orders for profitable ‘onsies and twosies,’ instead of focusing just on their runners, or high-volume parts.”

Irani added that a shop can perform the same kind of analysis on job margins. After all, a high-revenue, low-quantity job may look great, until you find that the high costs to produce the job make it a money loser.

When it comes to margins, to keep things simple and objective, Irani recommends using a job’s delivery time—that is, how long it takes from the initial order or order release to final shipment.

“At the end of the day, it’s about cash flow,” Irani said. “It’s money earned divided by the time it took you to earn that money.”

Irani added that focusing on order-to-ship time also puts scrutiny on outsourced processes. A job may flow through the shop in a matter of hours, but what if it takes a week or more to get those jobs back from a plating supplier, heat treater, or custom powder coater? Or what if a sourced component, like a motor or machined part, takes weeks to arrive?

Before all this, shop managers may have thought that a certain high-volume part was a bread-and-butter job, a true strength for the shop. But a detailed flow assessment reveals that the high-volume job really doesn’t produce as much revenue as it should. So instead of categorizing this job as a strength, the shop categorizes it as a weakness and identifies it as an opportunity for improvement.

Conversely, some parts may be low quantity, but it turns out that they in fact bring in a lot of revenue and are fairly profitable. Why? The jobs may require complex processing or highly skilled welders, or have some other trait that brings a higher price, perhaps because few if any local competitors can perform the work.

Lechleitner added that the job shop shouldn’t necessarily be looked at as one “business unit.” Instead, the reality should be driven by the data. A shop could have a few jobs that are ordered repeatedly and somewhat predictably, and those orders happen to flow through a similar routing. Meanwhile, numerous other orders may be highly unpredictable, have disparate routings, and yet be highly profitable.

Figure 2

This analysis compares part quantity with its associated revenue. In this case, the shop focused its improvement efforts in the outlined area. With this focus, the shop also can determine which parts in the bottom left cluster have the same manufacturing characteristics as those in the focus area.

In this case, a job shop really is two types of businesses under one roof—repeat contract work and low-volume job shop or prototype work. Analyzing these separately can reveal some big areas of opportunity.

“If you look at everything as one data set, you can hide some inherent problems, and you can also really miss these gems of opportunity,” Lechleitner said.

Considering internal strengths and weaknesses, SWOT not only incorporates the details revealed in the flow assessment, but other issues like skills gap and how well people work together. As Lechleitner put it, “Is there a skills gap that we also need to address? Are processes or information systems, including the ERP system, out-of-date or the wrong kind of system for the type of manufacturer we really are?”

Uncovering Opportunities

While strengths and weaknesses of SWOT define the current state, opportunities help a company focus on the desired future state.

Internally, a flow assessment may spur continuous improvement ideas, which are big areas of opportunity. A job shop could rearrange machines or processes in such a way that product families flow through the shop the same way. This could apply wherever it makes sense, such as to front-office workcells with people dedicated primarily (though not exclusively) to specific product families.

Opportunities also could be uncovered by analyzing highly profitable jobs. What makes these jobs so profitable? Is it the price the customer is willing to pay? Or does it have to do with how efficiently the job flows through the front office and shop floor? If it’s the latter, what about these jobs make them so efficient? Could other jobs be processed in a similar way, and if so, what needs to change to make that happen?

These questions could help focus continuous improvement efforts and guide future investments in people, software, and machines. This includes where and how these investments are used.

“For example, companies may buy a new piece of technology that can really help them increase throughput, but they then put that machine just wherever it will fit,” Lechleitner said. The result: A lot of the efficiencies gained from the new machine tool’s mechanical wizardry are mitigated by the fact that people need to shuttle parts back and forth across the plant to use the machine.

Externally, the opportunities and threats portion of SWOT takes into account how others view the business. “You need to address market share and how your company is perceived in the market,” Lechleitner said.

Part of this can be voice-of-the-customer research, not only with purchasing people but others at the customers’ plant—the people who actually work with a custom fabricator’s product—including engineers and quality personnel.

No Shortage of Threats

Last comes the threats part of SWOT. A customer’s market may undergo a disruption, perhaps a new technology that makes an entire product category obsolete. Global demand for certain products may be sliding, meaning major customers may reduce or halt orders altogether, or decide to bring the little fabrication work they have in-house.

A competing fabricator could take business away or up its game. As more shop owners reach retirement age, more custom fabricators are for sale, and with interest rates the way they are, buyers are swooping in. Those buyers may purchase a competing shop and decide to invest more in the business. The result: The competition just got better.

There isn’t any shortage of threats in this business. But the key, according to Irani and Lechleitner, is to base these threats on the current state of the shop, the true strengths and weaknesses, which guide opportunities that (ideally) should allow the shop to thrive, whatever threats may come.

As Irani summed it up, “When push comes to shove, all that matters is whether the shop can deliver every order it gets faster, better, and cheaper than any of its competitors.”

Exact Online, 260 Charles St., Suite 300, Waltham, MA 02453, 855-359-9256, www.exactonline.com

Lean & Flexible LLC, 4102 Pensacola Oaks Lane, Sugar Land, TX 77479, 832-475-4447, www.leanandflexible.com

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI