Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Expanding Their Reach

Expandable Casing Pipe Helps Oil Companies Drill to New Depths

- By Lincoln Brunner

- June 27, 2002

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

|

"The significance [to the oil business] is the ability to reclaim the lost diameter in the well plan as each casing string is installed," said Bill Dean, Business Development manager for Enventure Global Technology LLC, a Houston-based joint venture of Halliburton Energy Services and Shell Technology Ventures. "Periodically operators do hit unplanned situations in the drilling of their wells. The conventional solution is to install a standard casing string; again, that reduces the diameter. Solid expandables come into play, allowing that [extra] casing string to be run."

Enventure is the dominant user of expandable tubulars right now, having installed or expanded more than 46,000 feet of pipe so far, according to Dean.

How It Works

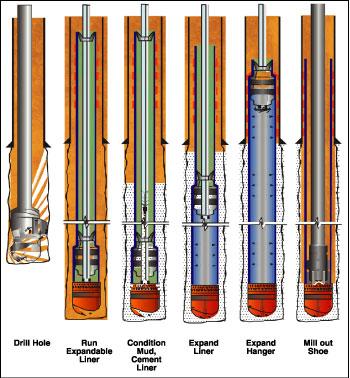

Open-hole Wells. You start with, say, a 3,000-ft. section of 95/8-in. steel pipe. You run it into the well (see Figure 1), pump cement between it and the outer wall of the hole, and pull a special mandrel called an expansion cone through it to expand the inside diameter (ID) to 113/4 in. before the cement hardens.

Why do it in the first place? Well, in a word, pressure—up to, say, 20,000 pounds per square inch total hydrostatic pressure during offshore, or open-hole, drilling.

"In order to continue drilling deeper, you have to case off the upper sections of the hole, because they won't allow that high pressure," Dean said.

Traditionally, mitigating those pressure differentials has meant running a succession of narrower and narrower pipe, one section inserted through the previous one, as a liner for the pipe that actually runs down into the ocean floor to extract oil from the deposit.In the words of Beau Urech, director of technical services for Lone Star Steel Co., Longview, Texas, currently the leading seller of expandable casing pipe, that telescoping effect actually can cause a drilling team to run out of hole — in other words, set so much pipe that there is no space left to insert the line that draws out the oil.

|

| Figure 1: The process of inserting and enlarging an expandable open-hole well casing is, mechanically, a fairly simple process. |

With the expandable casing, an operator runs a section of pipe into the well and then drops the expansion cone, which is moved by hydraulic fluid run through a smaller line that is connected to the cone (see Figure 1). As the cone is pulled back through the pipe with hydraulic and mechanical pressure, the pipe is cold-formed and expanded to its new diameter.

"[The expandable casing] mitigates the telescope effect," said Urech, a civil engineer who has been working on the expandable casing product with another Lone Star employee for about two years. "You may be able to pick up one or two extra strings of pipe in your well by using one expandable string."

In terms of the location at which the cold work is done, the expandable casing is a novelty, Dean said.

"This is the first application of the pipe manufacturing process [taking place] downhole in normal wall thickness casing strings, inside the well," Dean said. "Most tubulars run in the energy industry are sized at the mill, and then they're installed at that diameter. This is the first application of the solid pipe manufacturing process downhole in a live well."

|

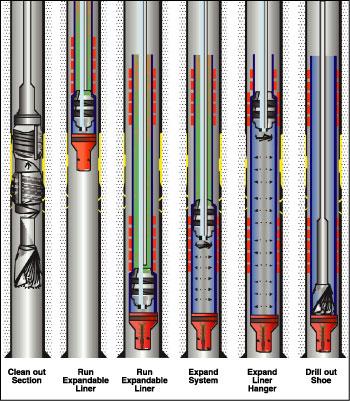

| Figure 2: The beauty of using expandable tubulars in land-based, cased-hole oil wells is that wells that might have been abandoned in the past now can be reclaimed. |

Cased-hole Wells. In addition to deep-water applications, Enventure is using expandable products to rejuvenate land-based, or cased-hole, wells too (see Figure 2).

Because cased-hole wells tend to corrode over the years, the companies that own them are looking for ways to extend their productive lives. Now those companies can go back to that well, drop a series of expandable casing strings into the well, and expand them to clad the inside diameter of the well hole. Voilà—new well hole.

(A Few) Material Details. Lone Star's Urech is reluctant to hand out much detail on just what kind of material goes into the pipe. It's safe to say it's taken some work to develop something strong enough to withstand undersea pressure yet pliable enough to expand up to 20 percent.

"The issue here [was to] devise a pipe that was strong but supple and a connection that could endure the expansion process," Urech said. "It's made of a high-strength steel that is tough and supple. A lot of thought [went into it]. It's been fun."

He added that the company came up with a manufacturing process designed to maintain the uniform dimensions necessary to ensure uniform expansion in the pipe downhole.

While the future market for expandable tubulars appears to be small in comparison with the rest of the industry, Dean said Enventure is encouraged by its numbers—numbers such as its 60 completed installations since work began in November 1999. Between land and sea applications from Nigeria to the North Sea, Malaysia to Oman, the company is beginning to get a little busy.

"We're getting that way, yes," Dean said. "It feels good."

Lone Star Steel Co., P.O. Box 803546, 15660 N. Dallas Parkway, Suite 500, Dallas, TX 75248, phone 972-386-3981, fax 972-770-6409, Web site www.lonestarsteel.com.

Enventure Global Technology, 2135 Highway 6 S., Houston, TX 77077, phone 281- 596-6612, Web site www.enventuregt.com. Graphics courtesy of Enventure Global Technology.

About the Author

Lincoln Brunner

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8243

Lincoln Brunner is editor of The Tube & Pipe Journal. This is his second stint at TPJ, where he served as an editor for two years before helping launch thefabricator.com as FMA's first web content manager. After that very rewarding experience, he worked for 17 years as an international journalist and communications director in the nonprofit sector. He is a published author and has written extensively about all facets of the metal fabrication industry.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI