Contributing editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Waterjet accelerates pace, provides speed secret

Winning the race between races

- By Kate Bachman

- May 8, 2007

- Article

- Waterjet Cutting

As you descend the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia south into sunny Huntersville/ Mooresville, N.C.—so-called Race City USA—you can almost feel the ground rumble. Eateries have names like "Pit Stop," and service stations are called "Raceways." Diehard race fans fan the area, taking two-wheeled corners while clutching cartoon tour maps and Lowe's Motor Speedway souvenirs.

The locals here are as hospitable as Southern folk are, but their drawl is slightly terse—those involved in the racing industry here are as tight-lipped as a small-mouth bass clamping down on a worm.

Race cars cross the finish line only fractions of a second apart. Shaving those all-important seconds begins long before the drivers scurry through the windows of their rides. A finely engineered and manufactured race car can be the difference between winning a race and placing or being shut out of the lead lap, and so "speed secrets" are closely guarded.

One racing company is not afraid of sharing one of its "secrets"—the use of a Flow International ultrahigh-pressure (UHP) Dynamic Waterjet® machine.

Weekly Races, Weekly Deadlines

NASCAR Nextel® Cup schedules 38 races a year, from February through November. For premier racing companies like Joe Gibbs Racing, Huntersville, N.C., that means production schedules are as tight as track turns at Bristol.

Joe Gibbs Racing sports three Nextel Cup teams, winning three Cup championships in a seven-year period. It also has two Busch series teams and manages diversity and driver development programs. It is the race team company of Washington Redskins head coach Joe Gibbs. Its Nextel Cup drivers Tony Stewart, Denny Hamlin, and J.J. Yeley are well-known race stars.

"Our deadlines are weekly, and every week there's a new race," said David Holden, research and development engineer, Joe Gibbs Racing.

Race cars burn through an engine every race, as well as other parts that must be replaced. "All we get out of a motor is just one race," Holden said. "So we'll manufacture in the range of 400 motors this year, and they cost $60,000 apiece."

Being Ready for Crashes. Intensifying the need for an ample supply of parts is that racetrack crashes are as common as tire changes.

"If you have a crash on the racetrack and you damage one of the parts that is your speed secret, you've got to have more," Holden said.

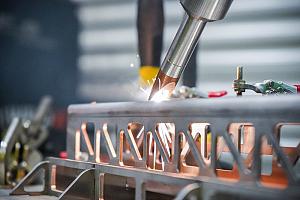

Figure 1Joe Gibbs Racing relieved schedule pressures with a Flow International ultrahigh-pressure Integrated Flying Bridge (IFB) Dynamic Waterjet. Nathan Kirkman (right) programs it on-the-fly, while David Holden obsreves.

"If you go to a race at Bristol and then to a race at Martinsville and then to a test at Richmond, you could potentially crash at all of those events. You have to be prepared for that worst-case scenario, and the worst-case scenario happens every now and then. Ideally, we'd love to have 50 parts, but if we can only have six, we'll take six," Holden said.

Putting supposition to the metal, in the Daytona season opener, Tony Stewart's car was wrecked after leading the race, and Denny Hamlin's car was damaged. Still, their cars had to be race-ready by the next weekend.

Gaining Competitive Edge. Too, there is constant pressure to gain a competitive edge every week that will rev up horsepower or improve downforce to make laptimes, Holden said.

"Every time we come up with a part development that we think is going to make the race car go faster, we've got to figure out how to manufacture however many of them we need for that weekend within a day or two to get those developments on the race cars," Holden said.

Mark Bringle, CNC and quality control manager, elaborated. "I call it the race between races, because, literally, it is a race to get these concepts to the cars as quickly as possible. We'll do testing over the weekend; Monday we'll see blueprints; and trucks leave with new parts on Thursday," he said.

"Our guys are constantly preparing cars for the weekend after next and the weekend after next and the weekend after next," Holden said.

Deadlines to Finish Lines

The midnight oil at Joe Gibbs burns hotter than motor oil. A staff of 24 engineers, 50 body fabricators, 120 mechanics in the chassis shop, 51 engine builders in the engine shop, and 29 CNC machinists work in two shifts, from 6 a.m. to 2 a.m., to try to help keep the race cars on track. Altogether, more than 400 people are employed at the company, including pilots, truck drivers, and administrators.

Even with the large staff and 24 CNC milling machines, rapid prototyping, laser cutting machinery, and other equipment in its technology center, the company had difficulty fulfilling all the parts needs for the cars. "We still needed capacity," Bringle added. "We were overloading our mills with work. There was not enough time on the mills to hit production deadlines."

Many of the materials needing to be cut, such as stainless steel—and some materials he can't mention—are very hard to machine, Bringle said. "With the properties of the stainless, you can only turn your rpms and your feed rate to the certain expectation of the tooling. Just roughing out the perimeter of an exhaust flange took a little over an hour on the mill."

To make some of the plate-thick components, the race company was purchasing torch-cut or laser-cut plate blanks, Bringle said. "The problem with 1-inch-thick plate that's been torch-cut is the edges are really nasty and very hard. So trying to machine a piece out of that torch-cut stock part is a terrible task."

Figure 2A motor plate (shown is the generation prior to the current version) is waterjet-cut before being milled, saving 40 minutes of mill time per part.

To avoid complications with flame-cut parts, the company sourced waterjet-cut parts from an outside vendor. But relying heavily on an outside vendor created drag on the schedule.

"We've got a very talented engineering group here coming out with a lot of great ideas," said Bringle. "So when you find a niche or something that will give you a competitive edge for that weekend, the crew chiefs don't want it sitting on the table for four weeks as you might if you're working with an outside company. They want it on the car that weekend."

Smoothing Speed Bumps With a Waterjet

The company installed a Flow International 6 x 12 Integrated Flying Bridge (IFB) Dynamic Waterjet in January 2006 (seeFigure 1). In some instances, parts are roughed or blanked on the waterjet before being mill-finished. In other cases, the waterjet cutting is the finish cut.

"We're able to produce more parts, we save machine time on the mills, and we're able to get better material utilization because we can cut parts out of sheet or plate," Holden said.

Timesaver. New parts often have to be re-engineered and refabricated. "When we first developed a motor plate [see Figure 2], we had some fit-up issues to deal with, so it needed several revisions," Holden said.

"Being able to use the waterjet to feed the milling machine was a huge timesaver for us," Holden said. "We took that motor plate out of the milling side and put it on the Flow waterjet and then did finish machining in the mills. So that really freed up mill capacity."

The 1/2-inch-thick aluminum 6061 motor plate, or engine plate, which supports the chassis, is cut on the waterjet in 11 minutes. A 0.050-in. stock allowance is left for a finish milling step, which takes 45 minutes. "Basically, we do a skim cut, just taking off the last little bit, and then the part's finished," Holden said. "We reduced mill time by 40 minutes per part."

An upper control arm plate that took 55 minutes to cut on a milling machine out of cold-rolled barstock is now roughed out of hot-rolled A36 plate on the waterjet in seven minutes and milled for eight minutes, Holden said. "Our initial run was 50; we calculated that we basically found an entire week's worth of mill time on that job, so that was huge for us."

Making Stainless Painless. Cutting the perimeter of the stainless steel exhaust flange took only 10 minutes (see Figure 3). "The waterjet doesn't care how hard it is or how thick it is. It's just easier to cut stainless on it," Bringle said. "We cut about 45 minutes out of a two-hour cycle time."

"Having more parts available because you've freed up mill time allows you to have parts prepped for the cars that are going in the following weekend," Holden said.

Figure 3Cutting the perimeter of the stainless steel exhaust flange and then mill-finishing it cut 45 minutes out of a two-hour cycle time.

Cold Cut, Not Torched. Now the company blanks thick plate parts on its own waterjet, Bringle said. "There's no heat-affected zone and there's no slag, so we can just go and mill it as if it were virgin material with no effort."

Versatility Enhances Speed. Waterjet's capability to cut different materials and thicknesses is extremely valuable, Holden said. "We use the waterjet for a lot of the variety of materials we use, from steels to aluminum, stainless steel, titanium, INCONEL® [alloys], and plastics about anything you can imagine you need to cut. Our waterjet is an all-around versatile team player that cuts about anything we need to do," he said.

"So we've got the operator already familiar with the programming interface for one material, and we've got the commonality of all the consumables," Holden said. "The operator aspect is big because the staff on both shifts run the waterjet. So if you had to cross-train multiple operators to cut different materials on multiple machines, it would get more and more confusing to train them."

Waterjet-finished Cut. The company waterjet-cuts more than 400 different parts, and about half do not require milling, according to Nathan Kirkman, who operates the Flow waterjet.

"We run typical tolerances of 0.002 inch on this machine, which allows us to do almost mill quality, and many of the parts are basically finished the way they are," Kirkman said, especially if they're not interlocking or sliding parts.

"We leave a waterjet edge on a lot of the stainless or INCONEL exhaust flanges, rather than going around them with a CNC—end mill," Kirkman said.

Flowing With the Changes

After the waterjet was installed, training was seamless, in part because some employees had used waterjet technology before, and in part because the machines are designed to be simple to learn and use. "It's a totally user-friendly software package and machine. We had it up and running the day it was installed," Holden said.

Being able to make program changes on the waterjet easily is important for cutting parts that often require several iterations, Bringle said. "It seems we're always making a skirt change. We'll make wind tunnel changes or vehicle changes to get more downforce. As the bodies develop and change, the skirts change to get the optimal length [see Figure 4]. The guys who hang the bodies always had trimmed those out by hand, and it was very, very time-consuming.

"Now we'll constantly go back in and revise that program on the waterjet, and since there's no setup time involved, we just pop it on our machine and make more parts," Bringle said.

Kirkman can operate the waterjet on-the-fly—programming it while parts are being cut.

Figure 4As the race car bodies develop and change, the skirts change to get the optimal length. They are now cut on a waterjet.

"This is a 9-1-1 machine," Kirkman said. "Guys will come down here and they'll say, 'I need something right now,' because they know I can do it without any setup. This is where you go when you want something quickly. You don't go to the milling machine."

It takes anywhere from 15 minutes to 30 minutes to program anything 2-D that is needed, Kirkman said. "Somebody can bring me a basic print like I have here, and I can turn this part around in a matter of 45 minutes—and that's pulling up the program, setting the machine up, and running it."

The machine also has 3-D programming capabilities, Kirkman said. "This is a big step for waterjets. It used to be just 2-D stuff. Now it can do angulars and different 3-D components like that."

The 3-D programming is a little more complicated, he said. "An engineer will submit a drawing, and I'll pull it up on the software, and a lot of times I have to modify their drawing, go in there and do my own 3-D modeling for my software."

Final Lap

Holden and Bringle said they thrive on being able to see the results of their developments every weekend. "It's being able to have that evaluation, that constant feedback—we won the race, we were second, third, fourth, we did a really good job this weekend. Other times it's really demoralizing when you realize that you've got a lot of development that you've got to do to make up for," Holden said.

"A couple of years ago, we went out to this test in Las Vegas, and we were terrible—completely terrible," Holden said. "And we all buttoned down and came out with all these new developments, new parts. In 2005 we won the championship. In 2006 we were third in the championship."

"I can't say which race, but we had some concepts that we were trying to get to the car, and the waterjet was very instrumental in doing that—talk about the competitive edge—we had a stretch there where we knocked out five wins in eight races with Tony Stewart," Bringle said.

"So we've picked up our level of competition," Holden said. "We wouldn't be able to do that without the technologies available and without the people in our technology center."

"Something else that's pretty amazing is that there are a lot of guys who go to the track every weekend, and they absolutely know they're not going to win," Bringle said. "If you look at all the technologies that go into a race car, and at everything that could go wrong for us to actually win a race, it's mind-boggling. To win three championships in the last seven years there are no words to describe it."

Heading up premier NASCAR® racing company Joe Gibbs Racing and being the son of famous NFL coach Joe Gibbs put J.D. Gibbs in "pole position"to develop a unique perspective on racing, competition, technology, and winning.

Do you go to every race?

I do! I used to be in the pit changing tires, and I drove for a while, but now, for the most part, I'm not allowed to touch anything; I just supervise. I can appreciate how hard those jobs are.

You've won three championships in seven years and 50 Nextel Cup® races. What does it take to win?

It takes good people and great partnerships. Home Depot, Fed Ex, and Interstate Batteries have been around a long time with us. There's a good bit of financial investment too.

This business is a little bit different. When you invest in new equipment, you don't do it because it makes business sense, based on returns and financial income. You're doing it based on how fast you go on that racetrack. You do it because it helps you win, because if you win, the rest takes care of itself. You have to win. You're only as good as your last race.

It's a close field. What happens now is, instead of looking for half a second, you're looking for a tenth. Getting that extra advantage is harder to do, but the better teams will still find a way to do that.

Now, a lot of it really is driven by technology. The human part is there, but you have to have technology, to get a little edge on how quickly you turn stuff around. It used to take over a year to build a car and design an engine. Now you can do it in weeks.

What does waterjet technology do for the company?

It took us awhile to figure out how to maximize its potential in our race shop, but now it's really cut down on time. This allows us to get those ideas implemented much faster than we could before.

Recent ethics infractions seem to reflect the saying, "You ain't tryin' if you ain't cheatin'."How do you think they impact racing's image?

One thing that frustrated my dad was the assumption that everybody's doing something. Well, everybody's not doing something. Certain teams are going to push the envelope, certain teams aren't. And we like to be in that category. We try to do things the right way.

We're going to push the gray areas as much as the next guy, but there are clear boundaries that you don't step over. That's just the way we operate. There are certain things you don't mess with, like the size of the engine.

How big is the NASCAR rules book?

Well, it's large, but it's still subject to NASCAR's interpretation. But they do a pretty good job. You know for the most part what they're looking for.

Those bodies have a lot of templates, but in between those templates, go nuts. You also know NASCAR might come back and say, "We don't like that."And you'll say, "It was within the templates,"and it was, but NASCAR will come back and make another template.

NASCAR will always allow some gray areas. They want you to be creative and make the sport exciting. That's what comes down to the people.

What are the major differences between today's cars and the NASCAR Car of Tomorrow?

The biggest difference is they're designed to be safer. I think also NASCAR has a little bit more control with the car. With the current car there're probably a lot more gray areas.

Their goal is 43 equal cars, and let those teams make the difference. NASCAR's hoping the Car of Tomorrow levels that playing field a little bit. You won't have to have quite the budget to compete, and maybe you'll win some races.

How will the Car of Tomorrow requirement affect racing?

You might have to invest a lot more to make that last little percent. So a lot of it will come back to people, how you set those cars up, the crews you have. Obviously, your drivers will always be a huge factor as well.

The problem is, right now, you have to R&D and build both cars at the same time, so you almost have to double what you're doing, and it's just a lot. We increased employees and increased a lot of investment. So it's expensive. You're kind of spread thin.

The biggest frustration is we probably have 60 race cars that will be obsolete in a couple years.

How do recent efforts to bring "green"to NASCAR, including the requirement to use unleaded fuel, affect the fabrication and manufacture of the cars"

It affects the engines. Unleaded fuel is a little bit harsher on those pieces and parts. It will take us awhile to figure it out to make sure we don't tear stuff up, but I do think it's the right decision for NASCAR. We'll figure out how to make it work on our end.

And then there are other things that we can do in the sport—things we can do here in our shop to make it environmentally sound—just commonsense things. I think that's the same for any industry. You're always looking for ways to take care of the environment.

How do you manage to keep your trade secrets secret"

Anything for which confidentiality is a big issue stays in-house. We have agreements with the people who work here and with the companies we have out-of-house.

The biggest thing you can do is retention—keeping employees here. To them, a trade secret is a competitive edge, so why would they tell someone else? It affects their bonus, it affects them, and they take great pride in what they do here.

What does the family-owned aspect bring to your company?

For us, my dad wants to pass it down to me and my brother, and we'd love to pass it down to our kids.

But beyond just our immediate family, a lot of the employees have been here a long time. For us, they're as much family as our immediate family. We'd like them to stay here.

Almost all the teams are within an hour's drive. Most of the guys could pick up their toolbox and go down the road and get more money.

What is it like to be involved in both the racing and football sports?

There are a lot of similarities between racing and football. Your quarterback is like your driver; your coaches are like your crew chief; your linemen are the guys that go unnoticed over here working on the race car.

But the biggest similarities are that you don't win with trick plays or trick parts. It's the people. We've got good people over here, and we've worked a long time to get that group together. That's how you win your games and races.

Do you think NASCAR is on-course to equal or surpass the NFL in television ratings? Do you think it will replace baseball as America's pastime"

You're not going to catch the NFL any time soon. It's just a different monster, it's kind of by itself right now.

When my dad first came to racing, he was in shock. Here in racing, you have drivers signing autographs a couple hours before the race. In the NFL, if you try to get an autograph before the game, you get arrested.

These drivers and teams know they wouldn't be where they are without someone else's help. They're appreciative.

I do think NASCAR is growing. They'll probably add a track in the Washington area, and probably another one in the U.S. somewhere.

Do you anticipate your season going longer"

I sure hope not! You know, the NFL goes hard-core for 16-plus weeks, but NASCAR goes for 38 weekends between all the practices and races. It would be hard to add any more.

What are your goals for Joe Gibbs racing?

From a competitive standpoint, we need to win races and championships consistently. If you don't do that, you're not going to be here for long.

From a practical standpoint, we want to be a place where the employees enjoy working, where they know we take care of them and their families.

Photos courtesy of Joe Gibbs Racing, 13415 Reese Blvd. W., Huntersville, NC 28078, 704-944-5467, www.joegibbsracing.com.

Senior Associate Editor Kate Bachman can be reached at kateb@thefabricator.com. Robert Runkle contributed to this article. Photos courtesy of Flow International except where noted.

Joe Gibbs Racing, 13415 Reese Blvd. W., Huntersville, NC 28078, 704-944-5467, www.joegibbsracing.com

Flow International Corp., 23500 64th Ave. S., Kent, WA 98032, 253-850-3500, info@flowcorp.com, www.flowcorp.com

About the Author

Kate Bachman

815-381-1302

Kate Bachman is a contributing editor for The FABRICATOR editor. Bachman has more than 20 years of experience as a writer and editor in the manufacturing and other industries.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 05/07/2024

- Running Time:

- 67:38

Patrick Brunken, VP of Addison Machine Engineering, joins The Fabricator Podcast to talk about the tube and pipe...

- Trending Articles

How laser and TIG welding coexist in the modern job shop

Young fabricators ready to step forward at family shop

Material handling automation moves forward at MODEX

A deep dive into a bleeding-edge automation strategy in metal fabrication

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- Industry Events

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,