Owner, Brown Dog Welding

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The jerrycan: History and design

A history lesson with all the makings of a Hollywood blockbuster

- By Josh Welton

- UPDATED March 1, 2024

- March 7, 2019

The plan was to write an article about how I turned an old military water canister, a “jerrycan,” into a rocket stove. In doing so I thought, “Hey, maybe a little background on the thing would give the project a little context.” I knew nothing of the jerrycan and its origins. A quick Google search should do the trick, right?

Instead I tripped and fell head-first into a series of rabbit holes. The story has all of my favorite things: crazy road trips; timeless design; metal fabrication; and a Nazi classified, secret weapon. What more could you want?

Perhaps an international man of mystery? This particular gentleman just might be the original “Most Interesting Man in the World.” If you know the history of the jerrycan, you probably think you know who Paul Pleiss is and how he was involved. You’d be wrong.

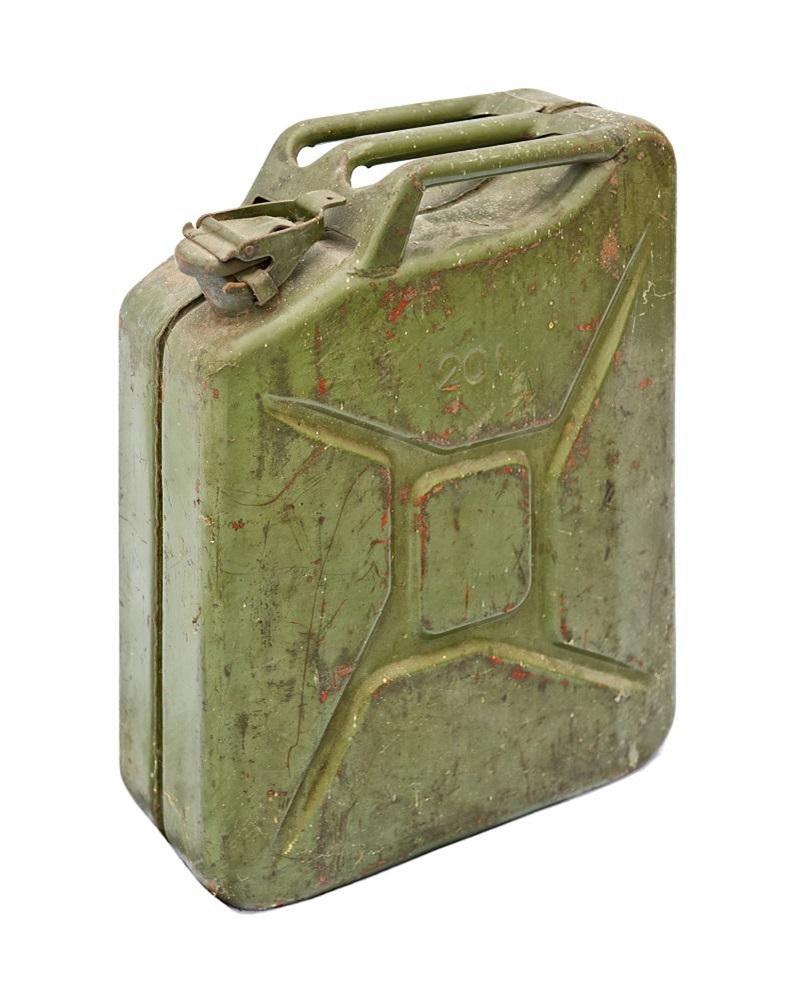

What Is a Jerrycan?

Then, of course, there is the jerrycan. It’s a small steel vessel that’s typically used to carry fuel or water in the military or on overland expeditions. The name points to its origin, as “Jerry” was a slang term for Germans used in the early 20th century by Allied forces. Some recent stories attribute the term to U.S. forces, but the Brits seem a more likely source: “One explanation derives from the hastily assembled, or ‘jerry-built,’ contraptions mocked by the British, while another stems from the way the German military helmet represents a chamber pot (jerry) or jeroboam (a wine bottle four times the normal size). A more prosaic explanation is that it’s a shortening of German.”

Germany developed the small tin in the 1930s to transport essential liquids during time of war, replacing old designs of basic triangular and rectangular shapes. Hitler demanded the upgrade; his evilness was rivaled only by his genius. He instructed his people to suss out the new design. They put out an “invitation to tender,” a competition, to come up with the slickest can. Through experience, Adolf and his advisers knew how critical a smoother, more efficient way to move fuel and water would be in their attempt to subjugate the world. If you can’t effectively lubricate your men and machines, then you’re not gonna last long in battle, especially in wars that were becoming increasingly far-flung and mechanical. The can’s apt original name, Wehrmacht-Einheitskanister, is German for “armed forces unit canister.” Vinzenz Grünvogel, chief engineer with the firm Müller of Schwelm, is credited with devising the winning canister. It might look simple, but there’s more to the design than meets the eye. The Wehrmachtkanister is form and function at its zenith.

“Developed under the utmost secrecy, the jerrycan featured flat sides that were rectangular in shape and was made in two halves that were welded together like an automobile fuel tank. It had three handles, which allowed it to be easily passed from one man to another; had a 5 U.S. gallon capacity, and weighed 45 pounds when full.

“Other distinct features included buoyancy in water, thanks to an air chamber at the top, and elimination of any need for a funnel, thanks to a short spout which was secured by a snap closure and could be popped open for pouring. A gasket made the mouth leakproof; pouring was easy and smooth, thanks to an air-breathing tube from the spout to the air space, and the inside of the can was lined with an impervious plastic material, which enabled the container to be used for fuel and water.”

The two flat sides of the can were stamped with a large X shape, aiding in both the can’s rigidity and its ability to weather changing temperatures, along with the gas volume fluctuations that came with them.

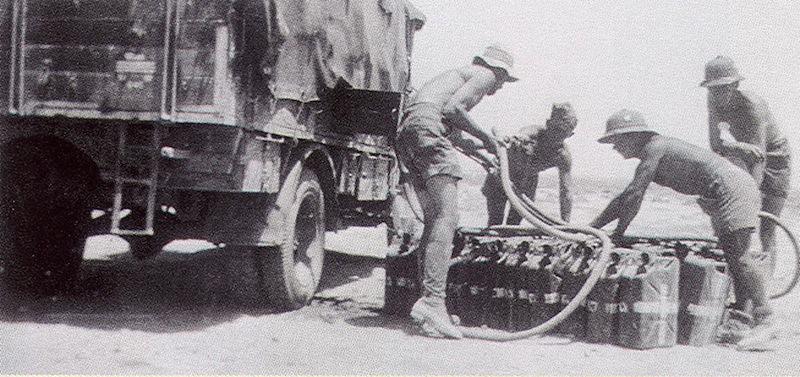

Meanwhile, the British and U.S. forces were utilizing their respective ill-thought-out containers nicknamed “flimsies,” There was no elegant solution, just a legion of light-gauge sheet metal pieces joined at harsh right corners with poorly welded, exposed seams. They were a hassle to carry and ruptured quite easily, neither of which are sweet attributes when transporting fuel under fire. And whereas the jerrycan is a self-contained unit, the flimsie required a wrench to open it, a spout to pour liquid out, and a funnel to receive liquid. “So poorly designed and manufactured, most were only able to be used once; they were then being modified for stoves, or filled with soil and used as makeshift sandbags.” (https://www.carryology.com/utility/carry-history-the-wwii-jerrycan/)

ABP Ambi-Budd Presswerk image found at http://jerrycansoftheworld.blogspot.com/2010/12/abp-ambi-budd-presswerk.html?m=1.

Despite the can’s obvious deficiencies in design and immeasurable failures, when presented with the answer in the jerrycan, the U.S. government ignored it. How they received this answer is a bizarre tale worthy of the Hollywood treatment.

“Early in the summer of 1939, this secret weapon began a roundabout odyssey into American hands. An American engineer named Paul Pleiss, finishing up a manufacturing job in Berlin, persuaded a German colleague to join him on a vacation trip overland to India. The two bought an automobile chassis and built a body for it. As they prepared to leave on their journey, they realized that they had no provision for emergency water. The German engineer knew of and had access to thousands of jerrycans stored at Tempelhof Airport. He simply took three and mounted them on the underside of the car.”

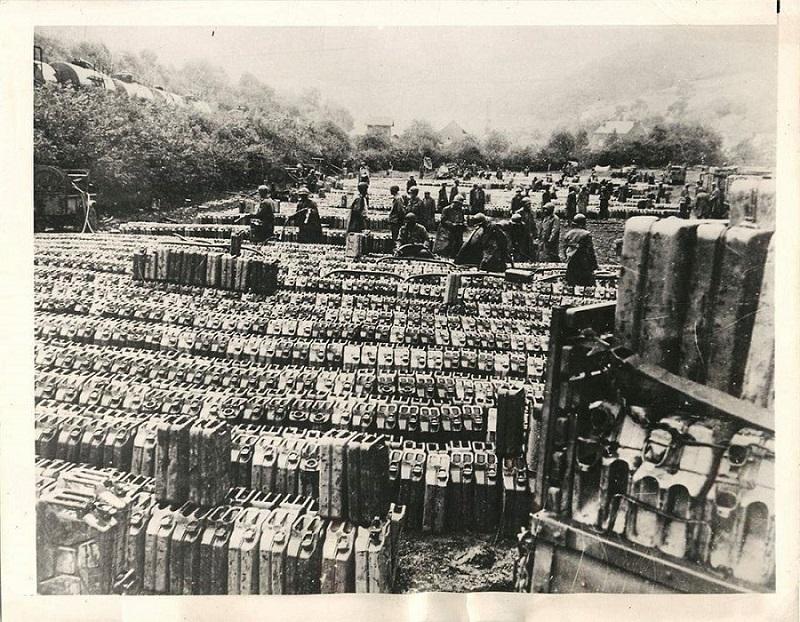

Sneaky. Keep in mind that up until this point the Wehrmacht had gone to great lengths to disguise and camouflage the cans. They alone counted for a valuable advantage over the Allied forces.

“The two drove across 11 national borders without incident and were halfway across India when Field Marshal Goering sent a plane to take the German engineer back home. Before departing, the engineer compounded his treason by giving Pleiss complete specifications for the jerrycan’s manufacture. Pleiss continued on alone to Calcutta. Then he put the car in storage and returned to Philadelphia.

“Back in the U.S., Pleiss told military officials about the container, but without a sample can, he could stir no interest, even though the war was now well under way. The risk involved in having the cans removed from the car and shipped from Calcutta seemed too great, so he eventually had the complete vehicle sent to him, via Turkey and the Cape of Good Hope. It arrived in New York in the summer of 1940 with the three jerrycans intact. Pleiss immediately sent one of the cans to Washington. The War Department looked at it but unwisely decided that an updated version of their container would be good enough. That was a cylindrical 10-gallon can with two screw closures. It required a wrench and a funnel for pouring.”

At some point an official at Camp Holabird came to possess one of the jerrycans, and at long last, the U.S. did try to copy the can. They skipped key design elements, however, which made the new tin as bad as the old. There was no improvement. Some people have a hard time seeing the forest for the trees.

Pleiss was an adventurer; in fact, I just read his essay on road tripping (in the same custom-built car) through South America, which was featured in the February 1943 edition of The Geographical Journey. While the Americans were busy not giving a hoot about these jugs, Pleiss was busy talking them up in England. If his Yankees wouldn’t succumb to reason, perhaps he’d find a willing party across the Atlantic. The Brits had been scavenging all the Nazi cans they could because, well, the German tins were awesome. They were curious as to how much info Pleiss had on them:

“Pleiss was in London and was asked by British officers if he knew anything about the can’s design and manufacture. He ordered the second of his three jerrycans flown to London. Steps were taken to manufacture exact duplicates of it.”

But again, nothing happened. Instead, Euro Allied forces continued to “capture” as many German vessels as they could, and it’s all they would use. The British military wasn’t at all happy that their government wouldn’t manufacture the things themselves.

Meanwhile, the U.S. was still fabricating and using garbage flimsies. Yeah, there were slight mods to the previous versions, but they still leaked and exploded and required tools to use. Chemical engineer Richard M. Daniel is the source for some of this part of the story. He was a quality control official at an American refinery in the Middle East, and by late 1942, the U.S.’s can’s flaws and consequences were too glaring to let slide. Battles were lost due to and victories won in spite of them. Daniel and a colleague filed a report saying some 40 percent of fuel was being lost in transport just because of the cans. “The 40 percent figure was actually a guess intended to provoke alarm ... it worked.”

A next generation of the American fuel canister was scrapped as everyone finally got on the same page and agreed that the Germans had gotten at least this much right. In preparation for a European invasion, the U.S. conceded production to Britain, which by 1944 had set up shop in the Middle East and was pushing legit jerrycans out in the tens of millions. At one point during the war there were around 200 factories worldwide that produced them. Late in ‘44 President Roosevelt stated that “without these cans it would have been impossible for our armies to cut their way across France at a lightning pace, which exceeded the German Blitz of 1940.” Hitler must have freaking loved that!

Daniel noted that very little about the jerrycan is of official record in Washington. According to him, there is one line in a report: “A sample of the jerrycan was brought to the office of the Quartermaster General in the summer of 1940.”

He’s not exactly right. In the Quartermaster Corps report put out in 1953 (volume 1, pgs. 143-144), another few paragraphs were dedicated to the can, although it’s mostly referring to the 1940 modified version that came from Camp Holabird. It’s the one Daniel derided, which the Army called the “blitz-can.” The report also says the Army received a “captured” can from Britain, then described the Allied forces’ eventual copy in 1942, an “updated” version of their blitz-can, not the jerrycan. There is no official record of Paul Pleiss’ road trip, and some believe it is fiction. I think there’s more to the story.

The Plot Thickens

Why is so little recorded in Washington about the jerrycan, a fuel and water container fabricated from stamped metal that was so instrumental in World War II?

I can’t help but wonder if maybe U.S. military leadership was none too keen on using this little marvel of German engineering—the jerrycan; were not happy when it proved to be better than their substitutes; and they were just fine talking up their blitz-can. Changing the name and the story would effectively bury/downplay how much of a difference the basically rebranded jerrycan made in the Allied victory. I feel that had the canister been something a little bit sexier, like a gun, or a drug, or a magic medallion, there would be at least one movie and three remakes by now.

Oh, wait. It gets sexier, actually. Earlier I stated that I went down some rabbit holes. A more accurate assessment is that I chose the red pill and jumped through the looking glass. It felt like every link and lead I followed turned up some new thread to tug on.

None of the online stories were complete in and of themselves, but eventually I could piece together a fairly consistent narrative. Of particular interest is Paul Pleiss, of course, the man identified as an American engineer who had just finished working in Germany before all hell broke loose. At the same time, Pleiss was building an overland vehicle and preparing for his epic road trip from Berlin to Calcutta. Every story, in one manner or another, told about his co-pilot, a German engineer who he roped in on the adventure, and how this man eventually used his knowledge of location and his security clearance to nab a few jerrycans just for use on their trip. They hid the cans under their vehicle and made it through almost a dozen border crossings before the German engineer was physically retrieved by the German army, though not before he basically gave Pleiss a blueprint for the Wehrmachtkanister. This would indicate that the German had an insider’s knowledge of how the can was manufactured, but it’s never specified how.

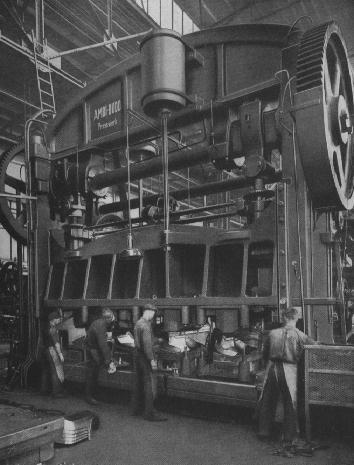

As I was truly attempting to put a nice, neat bow on my article, a blog post popped up about ABP.

Remember Ambi-Budd Presswerk? That’s the company that came up with the idea to build the can from two halves of stamped steel, which was key in making the original German canister so durable and simple to manufacture. Turns out ABP was a German division of an American owned steel stamping firm from Philadelphia named the Budd Company. This in and of itself isn’t crazy, as most German factories, even those owned by Americans, were commanded to support the war effort with their production. It’s this next part of the 8-year-old post on the blog “Jerry Cans of the World” that gave me pause:

“Paul Pleiss, the German-American manager of ABP, sent details of the new jerrycan to U.S. military officials, prior to the war.”

Wait, what? Pleiss worked for ABP, the company that helped develop and build the damned cans?!? If that’s true, was he actually involved in their creative process? If he first told U.S. officials of them before the war, not during it as presented by every other article I found, was he risking his life by contacting them from Germany? Did he build his automobile to hide the cans? Was the road trip for real, or was it a cover story all along? Did the German engineer actually exist, or was it part of a plan to conceal how much Pleiss previously knew, or how much he was involved in the jerrycan’s design?

There’s another piece of information in a collection of old Budd Company papers archived at the University of Pennsylvania. It expressed doubt over whether or not the parent company knew its German arm was being exploited to build for the Nazis, while also questioning the fate of ABP’s site owner, who was Jewish. Then this:

“Paul Pleiss, a party in the negotiations, did manage to smuggle the design secrets of the Ambi-built fuel can used by the panzers out of Germany later in 1939.”

Does this imply Pleiss knew about the canisters long before he was supposedly schooled on them by his driving mate on their way out of town? As the University of Pennsylvania acutely declares, the files are “tantalizingly incomplete.”

Who in Hades is this dude?

Finally, after many creative Google searches, I tracked down the obituary of Major Paul Pleiss in an archived New York Times paper from 1947. It was the only real info with any depth I could find.

Pleiss was described as an industrialist. Originally from Milwaukee, he graduated from the University of Wisconsin before joining the military. He served as an officer of the U.S. Army in both World Wars. He was the officer in charge of all nontoxic gases in France during World war II and then was part of the Balloon Division of the Aviation section of the Signal Corps. Still in his mid-20s, Pleiss was on the board of Burdett Oxygen and Hydrogen and wrote industry papers on different gases related to welding and manufacturing, along with books on manufacturing processes. He did R&D on high-altitude breathing apparatuses.

After serving as a board member of the Budd Company in Philadelphia until he was 37, Pleiss was put in charge of the company’s European activities in their entirety. The next year he organized the Pressed Steel Company in England, which came to employ 12,000 workers. He was credited with introducing mass production methods to car factories in Europe. That same year he became vice chairman and director of, you guessed it, Ambi-Budd Presswerk.

After retirement in 1938, Pleiss continued to consult the Budd Company on the stainless steel military cargo planes they were building stateside. During World War II he served as the European industry consultant to the U.S. Board of Economic Warfare.

In short, Pleiss was a brilliant engineer, scientist, leader, consultant, and highly involved Army officer. He was an industrial visionary who literally ran ABP when it was responsible for a breakthrough in how to manufacture the Wehrmachtkanister. Despite the can’s being a classified secret weapon, I have a hard time believing the unknown German engineer he traveled with had to enlighten him about any part of the can his company helped design and was building.

There’s no record of his earlier trip through Europe, the one during which he smuggled out the jerrycans, at least that I could find. But the essay on his South American travels was pretty much a straightforward assessment of his journey. Pleiss didn’t use hyperbole or colorful language, he just documented it. His trade essays were, more predictably, written in the same tone. This doesn’t seem to be a man prone to exaggeration; it feels like he’s a man of thought and action. Any way you take it, he definitely is someone who should be studied and remembered.

Back to our time, the can abides. And whether Pleiss designed the can for the Nazis, or stole it, or both, in the end the German’s once secret weapon helped spell their demise.

All images provided by Josh Welton obtained from his internet research.

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

About the Publication

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

The impact of sine and square waves in aluminum AC welding, Part I

How welders can stay safe during grinding

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI