Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Metal made wild

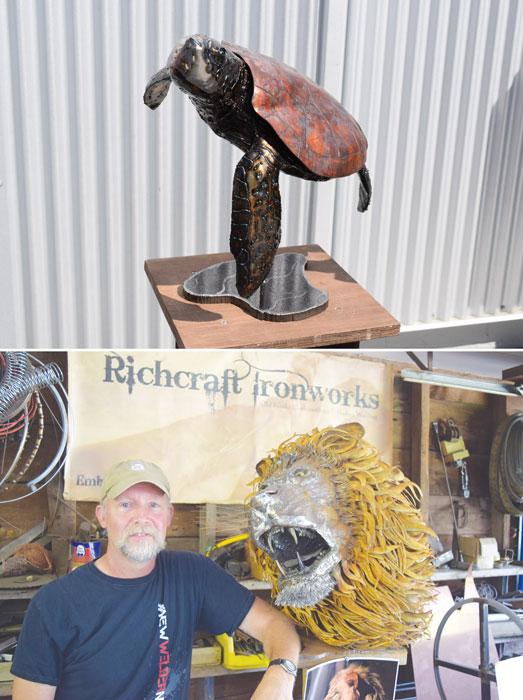

A welder captures nature in sheet metal

- By Rob Colman

- April 5, 2017

- Article

- Arc Welding

This hawk is a bird native to South Africa. Baker captures the bird as life-like as he has by cutting and etching each feather individually. The patina is created with the use of a chemical spray.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September 2016 issue of Canadian Fabricating & Welding.

Rich Baker is someone who always understood the beauty involved in a solid weld, but if you told him 20 years ago he would be making a living as a welding artist, he might not have believed you. Yet for the past six years, Baker has continuously developed his skills as a sheet metal sculptor, creating vivid 3-D representations of everything from people to peregrines. Richcraft Ironworks has drawn customers from around the world, thanks to Baker’s attention to detail.

From Steel to Wheels and Back

Baker started his welding career as a young man working for United Steelworkers. When his job was moved south of the border and welding opportunities in his community were scarce, he (with encouragement from his brother) taught himself to play guitar.

“I spent six months doing nothing else but learning that guitar and applying for jobs,” Baker recalled.

That determination with the guitar paid off. He spent the next 14 years on the road playing in his own band. The band played the Ontario circuit of clubs and bars, and even toured in the U.S., playing covers and some of Baker’s own songs. When he met his wife and started a family, he stopped touring but kept writing music. Over time he penned a number of hit country songs with musician John Landry.

But music is a fickle business, so to support his family, Baker eventually went back into the welding trade. He landed a job at the GE Power plant in Guelph, where he eventually ran the weld shop.

“I was there for about four years,” Baker recalled. “It was a great job, but after so many years on the road I found it really difficult working inside all day. I just couldn’t adjust.”

Baker’s wife encouraged him to make a change to a job that would allow him to be outdoors more often. The couple lives in farm country just south of Stratford, Ont., so setting up a business doing weld repairs on farm implements seemed a natural fit, and that was Baker’s plan.

But while he was prepping his shop to serve the agricultural community, Baker got a wholesale contract to make figurines out of old-fashioned nails that he would weld together. Over the course of six months, he made musicians, family scenes, and many other pieces using this one basic material.

Up to that point Baker had never worked with sheet metal. All the welding work he’d done was on structural steel and heavy machinery. His first attempts at sheet metal figures were a couple of carousel horses, each crafted out of two small pieces of metal.

“I created a design in cardboard, then cut the metal and welded it together,” he recalled. “I think the problem with that at the time was that I was thinking in 2-D, maybe because it was carousel horses I was modeling them after. If I were to make the same horses today, I’d use way more pieces to sculpt the shape.”

3-D Breakthrough

The breakthrough in sheet metal came for him when a friend of a friend asked Baker if he could build him a model train—a three-truck Shay locomotive, to be precise. Baker had no idea what a three-truck Shay was, but he’d never been one to say no to a challenge. This was his first true success as a sheet metal artist. Looking at pictures, you can see the attention to detail he gave to the train and its engineer. He even used a roof shingle to re-create the look and texture of coal in one of the trucks.

Baker is never daunted by a challenge. If he wants to understand something, he’ll work at it until he masters it. His approach to the work of sculpting, for instance, changed quite quickly. Instead of cutting out cardboard sections and trying to piece together the figurine like he did with those early horses, he now allows the work to evolve in his shop.

Now Baker often finds a number of images of a particular animal online, prints them out, and posts them on the wall of his shop. These might stay there untouched for a number of weeks as he works on other projects, but he’ll revisit them regularly as the wheels turn in his head, considering how he might best re-create the look of that animal.

Baker uses 4- by 8-ft. sheets of mild steel, in around 22 gauge and higher.

“I want to be able to manipulate the steel with ball peen hammers,” he explained. “The less heat I have to use to form a piece the better, so that I don’t get discoloration in the metal from that process.”

Most of the welds Baker makes are stitch welds. Again, this is to avoid too much discoloration on the steel during the welding process. As he finishes sections, he’ll grind the surface sometimes to capture the texture of fur on an animal’s body.

Every project Baker works on is trial and error. “I take photos at every stage of development on a sculpture, and it’s amazing how often I look back on a project and think, ‘No, I wouldn’t build it like that now.’ My process is always evolving,” Baker said.

About the Author

Rob Colman

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI