Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

What a structural steel fabricator can do to prepare the next generation of welders

A welding training specialist talks about what Able Steel Fabricators has done to replace the experts heading for retirement

- By Dan Davis

- January 13, 2023

- Article

- Arc Welding

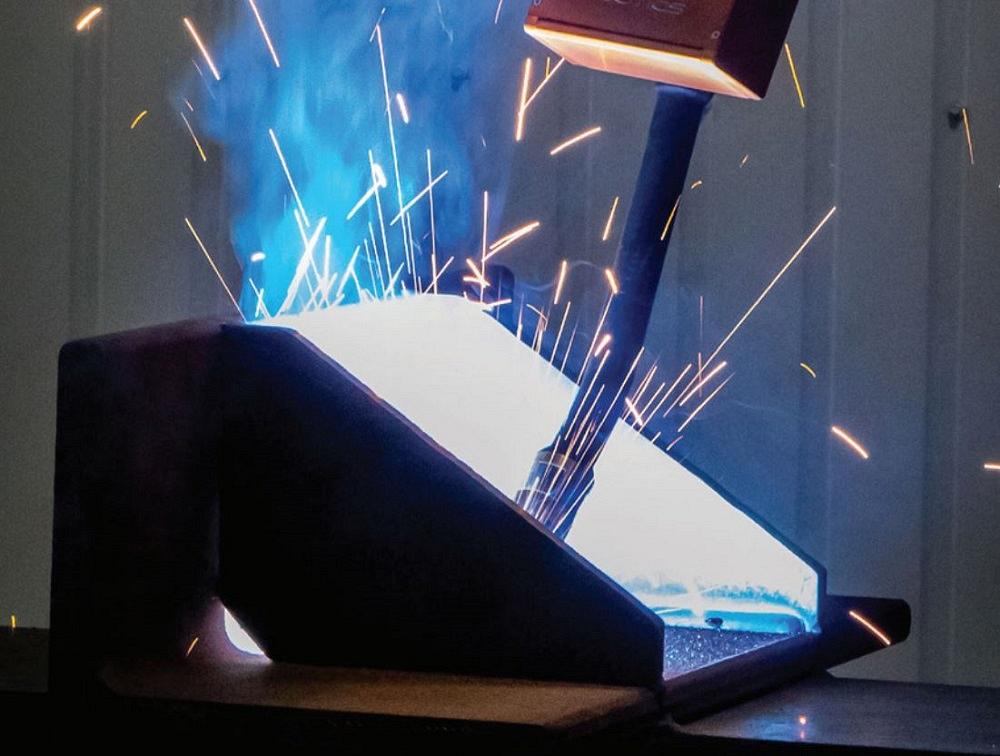

Able Steel certifies its welders to work in the 2G horizontal position, like in this photo. It uses welding positioners to ensure that welders don’t have to work in vertical or overhead positions. RayOneMedia/iStock/Getty Images Plus

The impending retirement of thousands of manufacturing veterans is no secret. What fabricating companies have done to address this situation, however, is not so widely discussed.

Able Steel Fabricators, Mesa, Ariz., has grown from a small structural steel fabricator, building grain storage facilities and mini-storage facilities in the 1970s, to one of the largest structural and miscellaneous steel subcontractors in the Southwest. Some of its recent projects include the Arizona State University College of Nursing in Tempe, Ariz., and the Western Regional Medical Center in Bullhead City, Ariz. Today, the company has about 60 employees.

Kenny Hicks joined the company in 1978 and worked his way up to quality control manager. Except for a few years when he had an organ transplant and lived out of state, he has worked for Able Steel for longer than some of his co-workers have been alive.

Around 2018, he began thinking about retirement and possibly relocating somewhere else. That’s when Able Steel management approached him with a couple of new challenges. Would he be interested in checking all drawings for correct details before they hit the shop floor? Also, would he be interested in launching a training program to help younger welders make the transition on the shop floor? Both job duties needed a knowledgeable and skilled individual to help the effort, something that was not going to be easily found with an online job notice.

Roughly four years later, Hicks is thinking about retirement, but Able Steel is in a better place because of his work. The FABRICATOR spoke with him about what he has done to prepare new employees for their fabricating roles at the company.

The FABRICATOR: In your new role as a training specialist at Able Steel, where did you first focus your attention?

Kenny Hicks: So, I thought about it a while and started developing a training manual, which would help facilitate my training program. Now I look at it as a live document. I’m continuing to add to it.

It’s gotten pretty thick over the years, but it covers a lot. Some of the basic stuff includes instructions on how to properly run a plasma cutting machine, for example. I have given them the step-by-step instructions in writing. Then, I concentrated on blueprint reading, starting with beams and columns. More recently, I’ve added lots of stuff about weld distortion and flame straightening.

I basically dumped 38 years of experience into this manual and into the program.

What I also did was then turn my focus on the training or the welding programs in my area, starting with the six high schools here in Mesa. I reached out to them, introduced myself, and then started coming in, introducing Able Steel to the students.

Once a new employee passes a fillet weld test, he gets a copy of the Able Steel Training Manual, which covers everything from blueprint reading to working with robotic welders. Able Steel

Then I started hitting the technical schools, such as Mesa Community College and East Valley Institute of Technology, just getting involved in their welding programs and introducing myself and my company.

At those schools, I mainly focus on those second-year students—the ones who are about to graduate. I spend time with them in the welding shop basically trying to establish a relationship with them, so they know who I am and understand that I care about what they’re doing.

I know that all of these young people are interested in welding. They took welding in high school, or they’ve just paid to take a welding class in junior college. I pretty much concede they’ve got that interest. Able Steel knows that we can train the rest of what they need to know. Once we get them on board, we have to make them comfortable. Mostly with the younger students, they’ve never been in this environment. We’ve got overhead cranes, lift trucks running behind them, and sparks everywhere. It’s intimidating.

FAB: How do you help them make the transition?

Hicks: What we do here at Able Steel is we don’t give up on them. We give them their fillet weld test, and if they bomb it, then we put them in parts, which is basically material handling. We stick an iPad in their hand to help them with that job.

I also start spending time with them each day, just to keep them moving along, mainly so that they don’t get discouraged because they bombed a test. I find that half of what I do is building confidence in these people. The training part of it is the easy part.

It’s understanding the personalities and then trying to find a way to boost that. So, if they’re working in our parts department, they are learning how we operate. They are going to end up walking through the whole plant, meeting other employees, and getting comfortable with this environment.

After a while, I’ll see if they want to take another fillet test, and we’ll get it all set up. They’ll take it again, and when they pass it, they can come out and start fillet welding.

FAB: What happens when they are ready to hit the shop floor?

Hicks: Once they get out into the shop, they’re going to do 40 hours with another employee. We pair them up with another experienced employee and that's to help them get their feet wet. They’ll learn things like where everything is at, what PPE is needed, and where to get tanks changed out.

Able Steel has one AGT BeamMaster robot welding system, such as this one, and has plans to possibly add another in the future. AGT Robotics

During that time, and at the end of those 40 hours, I’m in there just about every day, talking with them and keeping them moving forward. Then they get the training manual.

FAB: What will a new employee see when they first jump into the manual?

Hicks: One of the first pages I’ve got in there is going to tell them what tools they are going to need and other additional tools that will help them in their career.

I’ve also included a way of teaching beams and columns that is useful. I don't know what other fabricators do, but I like to look at a column as having A, B, C, and D sides. I line them out with that. When they get their first column, they are going to mark it with an A, B, C, and D on it.

Then we move into talking about our section views. We’re going to look at the offsets in those connection plates, and that’s when I’m explaining to them that when structural steel is erected, it’s about bringing all their centers together. All these loads are transferred on centers. So, for a beam to come to the center of a column, that connection plate needs to be offset half the thickness of the web of the incoming beam. As I’m teaching this, I’m explaining why we’re doing it. They need to understand it. I mean, just telling them that this is going to offset to the near side or this is going to offset to the far side—that’s not really enough.

After they’ve got the A, B, C, and D marked on their column, I just have them put a little arrow next to that. I remember that in my years in quality control, the errors in columns normally aren’t in the linear; they're in the offsets. When people start rolling their columns, you’re going to fit all four sides, but you’re going to fit one side at a time. As you roll your column, your mind’s eye gets confused. What was near side? What was far side? What was left, and what was right? As you’re rolling the column, you get discombobulated. By marking the column with A, B, C, and D and putting the arrows on it, that stress is out of the way. Because they took their time, all they really have do is look at what side they’re on, look at the arrow, and continue to fit.

The columns are the hardest part. Beams are generally much easier. They’re near side or the far side. Then you have your linear running dimensions. It’s fairly easy.

One of the things I would add is the fact that I check every drawing before it goes out into the shop. We use three or four different detailers, and I’m able to keep the drawings consistent. That’s important for someone learning.

If you’ve been in the business a while and worked with different drawings, you can see that while there are rules to detailing, detailers tend to have their own style. So, what we did here at Able Steel is create detailed standards. It’s very clear what we want in our drawings.

FAB: Looking at the recruiting side of your job duties, how many people have you brought over to Able Steel?

Hicks: I’ve been doing it since 2018, and I probably would say between 50 and 70 people. Are they all still here? No.

That’s something that we’ve dealt with here at Able Steel. The company has increased the wages and remained competitive with other fabricators, so that as we get these people trained up, they don’t go to another fabricator and use those skills that I just taught them.

It was a learning curve for the company early on, but we’ve dealt with it. We’re having better luck with keeping employees now.

FAB: What sort of advice do you have for other people that might be in a similar position and looking to attract more potential welders to their companies?

Hicks: Once you have established yourself with local welding instructors, you can look into joining the advisory boards that work with these schools. I’m sitting on two different advisory boards right now. That’s where I can have input and get their program to at least produce a student that we might be looking for at Able Steel.

And don’t just join it, be active. Be vocal. That’s what they want—to hear from us.

Once you’ve established that relationship, recognize that all of the schools need scrap steel.

FAB: How many welders do you have on staff at Able Steel?

Hicks: We have about 60 employees now, and I would say 25 are welders. Of course, our goal is to have welder/fitters. We do have fitters that do nothing but fit, but only because they’re much faster, and we can get a stack of beams out of their station much quicker.

The goal when I’m training is to get them trained up for fitting, and then work with them to get them certified with us. Our certification is 2G horizontal with 1 in. for an unlimited thickness. That certifies you for flat and horizontal. We can position everything else. There are no vertical and overhead welds to worry about.

Our goal is that we can bring something, drop it at this person’s station, and have him fit it up. Quality control will give it the OK, and then we can just leave it there. It’ll get welded and out the door it’ll go. Otherwise, it gets moved to a welder.

FAB: How long does it take for a new welder to become a certified welder usually?

Hicks: We encourage them to try and get the certification before the 90-day review. If they have their certification, they’re going to go into that review in a much better position.

FAB: Has the way welding is done at Able Steel changed greatly in recent years?

Hicks: We bought an AGT Robotics BeamMaster and LayoutMaster recently. Right now, we have one station, but the company is looking to bring in a second station, which will make two robotic welders. I don’t think we’ll be bringing in a second LayoutMaster with the other BeamMaster.

This is a direct result of what’s going on in world. The company wants to remain competitive, but if people don’t want to work, we’ve still got to keep up with our production schedule. So, we’ve had the robotic welder up and running for probably four months now. We’re still learning how to make money with it, but we’re getting better at it.

If we made widgets over and over, the robot would be perfect. But every beam is different. Every column is different.

I’m lucky because I'm already looking at the drawings, and I’m looking at them before they are released to fabrication. I’m identifying those jobs that we can steer towards the robotics.

When the workpieces make it to the parts department, that’s where they are segregated. Some go to the welders, others go to a robot.

What we do is we wait until we have a batch, and then we do a production run. We’re not going to run one onesies and twosies through the robot. We get everything staged and ready so that we can get the maximum efficiency out of using the robot. We don’t pull the trigger until everything is sitting there ready. And then when we pull the trigger, and we are seeing good results.

In the beginning, we were collecting every beam or column that had more than 150 in. of weld and just sending it over to the robot. The 150 in. of welds seems to work for the robot, which has two cells. You can put a piece in one cell, get it all laid out, and get it all fit-up. Then, when the robot comes in and welds, you move to the next cell and start laying out and fitting that one. You just basically switch back and forth until you’ve run your whole batch. Anything less than 150 in. of welds, and it welds too fast. You can’t move that quick.

FAB: Have any of the employees gravitated to this automated welding?

Hicks: When we started off with it, we started with an older worker with experience. He came back to the boss and said, “Look, I’m just not interested. I think I can fit faster than this and better than this.”

We actually moved from an older guy to a little younger guy, and right now we have two guys on it who absolutely love it. We’ve trained them up and they’re making it work. They are not intimidated by technology.

In fact, I’m running a simulation right now on a batch of 80 beams. When I get done, I’m going to produce a report, and within that report it gives us a percentage of total welds. Remember, it’s pulling off the Tekla model, and it’s pulling all the X, Y, and Z data from that model. The report will give us inches of weld, and we can use that for scheduling.

I can filter the report to put the highest number inches of weld at the top and the lowest number at the bottom. The production plant manager has access to Tekla, and when he needs to send something to the welder to keep him busy, he can grab a beam with 200 in. of welds on it, not one with 800 in. of weld.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI