Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Service center/stamper/fabricator wants to do more

PMI leans on its metal processing know-how and automation to stay on top of its opportunities

- By Dan Davis

- November 11, 2019

- Article

- Automation and Robotics

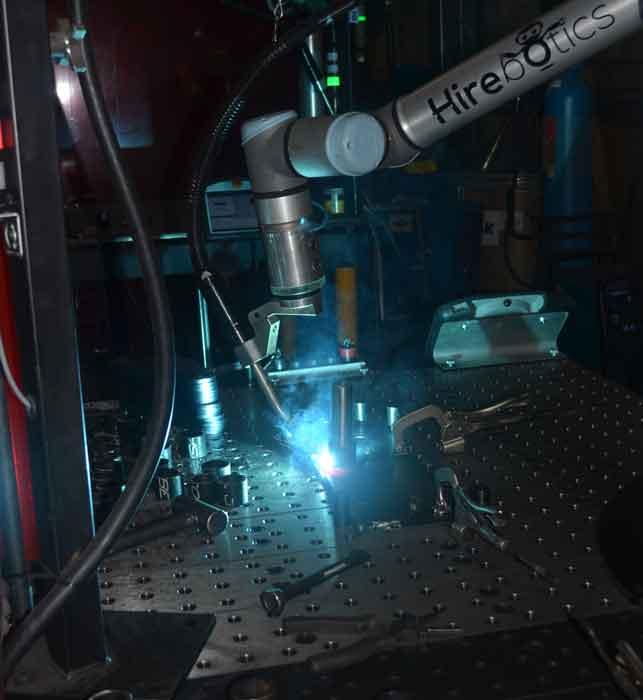

A collaborative robot, or “cobot,” welded this part at PMI LLC in Bloomer, Wis. In fact, Hirebotics, the company behind this automated welding cell, has updated the cobot’s welding capabilities after receiving feedback from PMI’s robotics team. These updates are delivered to the cobots via the cloud.

Eric Lewis is the plant manager for PMI LLC, a service center/stamper/fabricator in Bloomer, Wis. His title wouldn’t suggest that he’s an aquatic vegetation specialist, but he was on a lake in September scooping out weeds as part of a community effort to clean up the body of water.

That’s not out of the ordinary for the company. It’s a fixture in this Chippewa Valley town of 3,500, and management views this type of activity as being important to raising the profile of PMI with not only the community, but also its employees. That’s why the company also is involved with the local food bank, the town’s emergency services, and vocational programs at Bloomer High School and Chippewa Valley Technical College.

“We want to be seen as a leader in the community and as a place the people want to come work for,” Lewis said.

Some may view PMI’s community philanthropy as being a natural extension of life in a small town. That’s true to a certain point, but this is part of a bigger plan. PMI needs manufacturing talent.

Situated between the Twin Cities in Minnesota and the large Chicago metropolitan area, PMI finds itself in the middle of plenty of economic opportunities. That’s why it has been successful in diversifying its customer base over the years, serving the appliance, automotive, defense, and energy industries.

As these companies have grown, so has PMI. Over the last couple of years, the company has seen 10 percent year-over-year growth, according to PMI President Chris Conard. Today the manufacturer has about 145 employees; three years ago it was only a 70-employee operation.

So the community engagement is not only about being a good corporate citizen. PMI wants to attract workers so that it can continue to grow with its customers.

“We were offering $15 per hour for new entry-level workers for a long time before you started hearing the call by politicians to raise the minimum wage to that level,” Conard said.

The Value Proposition

PMI is somewhat unique in that it serves a variety of roles to manufacturers. Conard estimated that the company earns about 20 percent of its revenue from service center processes such as coil slitting, blanking, and leveling; 50 percent from stamping; and 30 percent from metal fabricating.

How did PMI become involved in all of these activities? Well, the answer requires a short history lesson.

PMI is somewhat unique in that it is a major coil processor as well as a stamper and a metal fabricator. Its building has rail access so that coils can be shipped cost-effectively to its facility.

Processed Metals Innovators was created in the early 1990s when six employees from a local door and window manufacturer were charged with starting a company to develop products for manufacturers outside the residential home construction sector. (One of PMI’s first jobs was taking overrun from window production at the door company and creating a part from it for a freezer application for a major appliance company.) Those employees took their coil processing knowledge and got to work building up a business that ultimately led to more metal forming and fabricating work.

In 1998 PMI moved into its current location near some tracks, which would prove beneficial for receiving coil by rail. Since then it’s added on several times for additional manufacturing and office space. The campus on 21st Avenue is now approaching 150,000 sq. ft.

The company’s evolution has become a welcome occurrence for some stressed purchasing agents, Conard said. In many instances, PMI is able to handle several aspects of the part production cycle, allowing customers to rely on one vendor.

For example, because PMI maintains a stock of metal inventory, when an urgent order comes across, it might already have material in stock. The customer doesn’t have to worry about wasted time, whereas another fabricator might have to chase down the material. Additionally, because the material is on hand and it is one of the few steel manufacturers that also has in-house coil processing capabilities, PMI can turn around large jobs more quickly than other stamping and fabricating competitors. It also helps that, in addition to common hot-rolled carbon steel material, PMI works with cold-rolled, galvanized, and prepainted steel; aluminum; and stainless steel.

“Any customer saying that they are not making a decision based on cost is lying to you,” Conard said. “Of course, they need delivery. But the price has to be right, and that’s what we work to address.”

That’s a little bit more difficult when you simply can’t throw more labor or expertise at production challenges that can help you meet the goal of being an on-time provider of quality and cost-effective parts. That’s why PMI has been aggressive in manufacturing technology investment over the past three years, Conard said. Specifically, it has spent about $6 million in capital equipment over that time. Technology is helping PMI stay true to its mission and giving it the opportunity to continue to grow with its customers.

Cobots Help out Stamping

PMI has a robust stamping operation. It has presses ranging in size from 75 to 2,000 tons, handling gauges from 0.008 to 0.375 in. Twelve presses are coil-fed, and five are manually fed. (PMI has some very large stamping projects. For example, it stamps about 1 million steel door skins per year for a major door OEM.) Earlier this year the company introduced cobots to the material handling mix.

(The word cobot is short for “collaborative robot,” a light-duty robot that is designed to work alongside humans without the need for guarding. If these robots come into contact with a human, they are designed to shut down. Because they move more slowly and are much lighter than industrial robots, they don’t pose as much of a risk to humans.)

PMI officials reached out to Hirebotics, Nashville, Tenn., to help integrate some material handling cobots into a stamping line for generator parts. The cobots would help to free up some labor from the task of loading parts into a press, removing them, and loading another blank into the press.

“This type of investment is important because it helps us to keep up with work even as the market is getting tight for labor,” Conard said. “You don’t want to have to say no to a customer because you can’t take on their work.”

A Hirebotics cobot removes a part from the stamping press. It’s one of two cobots on this particular press line.

Hirebotics is giving companies like PMI the chance to dabble in automation without having to make a large investment in equipment and adding robotic specialists to the payroll. The company rents the cobots and helps to set them up for the particular application.

Since this spring PMI has been using two of the cobots on the generator stamping line. The cobots feed and remove generator parts from the dies of a 400-ton Danly press and 250-ton Warco press. The two presses are sandwiched between a manually fed press on the front end and a back-end operation where an employee manually finishes off the freshly stamped parts for downstream operations. Instead of the stamping line operating with four employees, only two are needed. Conard also pointed out that the use of the cobots is just another example of the company trying to keep costs down for customers.

Using robots to feed and remove parts from a stamping press is not unique. Applying the use of cobots to welding, however, is something totally different.

Cobots on the Welding Job

The lack of people pursuing welding training is worrying industry quite a bit. In fact, the American Welding Society estimates suggest that industry will be short some 200,000 welders in 2020 and nearly 375,000 welders by 2026.

Joe Holloway, senior vice president, Red-D-Arc Inc., Atlanta, said his company has been watching this trend develop over the past couple of decades. The welding equipment rental company had long been involved with the fixed automation side of welding, providing turning rolls, manipulators, and positioners to manufacturing customers, but they had never been heavily involved with “flexible” automation, Holloway said.

“It never looked to be a rentable product just because of the complexity of the robots and teaching people how to program,” he said.

The thought process evolved a bit after Holloway read about Hirebotics in some industry trade journals in 2017, one of which was The FABRICATOR. The Hirebotics cobot technology looked interesting, but it had never been used in welding applications before. Also, Holloway wondered if it were scalable, so that it could be made available to a large portion of manufacturers in the U.S. He decided to begin conversations with Hirebotics to see what might be possible.

Around this time Holloway took the opportunity to collaborate with Air Liquide colleagues at the Advanced Fabricator Center in Delaware, where they were researching and developing automated welding cells involving cobots. (Airgas is the parent company of Red-D-Arc, and Airgas is a subsidiary of Air Liquide.) The effort was about to take off with the introduction to Hirebotics.

Hirebotics had a good control system, but it had not been adapted to welding. Air Liquide’s engineering talent was able to help them develop recipes that would allow the easy-to-program cobots to start laying beads after only a short amount of teaching time. Gone would be the pendants and the advanced robotic knowledge necessary to get industrial robots and automated cells working. The BotX Welder was born.

“We wanted to make it as simple as possible for people to use,” Holloway said. “What we’ve done is develop this library of welding recipes that not only have the voltage and wire feed speed for whatever the application is, but it also controls the robotic arm as far as travel speed and the proper angle of the torch. The customer can then test and fine-tune to achieve their engineered specifications.”

A cobot welds a joint around a cylinder attached to a plate. The part is one of several the cobot welds for PMI.

With PMI already being a customer of Hirebotics, the fabricator was a natural—and willing—participant to try out this technology. It decided to rent two BotX Welder packages, which included a Universal Robots UR10e cobot arm, a connector to the cloud-based internet, a Miller Electric welding power source, a wire feeder, a robotic gas metal arc gun, a modular welding table, and the Hirebotics app and software to control the system. PMI has to provide the operator, gas, wire, and parts. Because the collaborative robots do not require safety fencing like industrial robots do, they take up about the same amount of room as a manual welding cell. In some cases, it could be about half the floor space of traditional welding automation.

The results from a summer working with the two cobots have proven promising, according to PMI officials. Erik Larson, PMI’s vice president, operations, said a lead from the stamping area, who had worked with the Hirebotics cobots, was assigned to work with the welding cobots. He had no welding experience.

“When you watch them program one of these cobots, it’s move the arm, press a button, move the arm, press a button. You don’t need welding experience to get it working,” Larson said.

Larson added that the modular table aids quick turnaround on small welding jobs. While the programming can take about 30 to 45 minutes, the table can be set up in a fraction of that time because of similar-sized bore holes that accommodate the same size brackets and fixtures. The fixtures are made to be used with the welding table. Clamps can be used easily with the table as well. No custom fixturing is required.

Additionally, Hirebotics is constantly updating the control’s recipe list. Holloway said if an improvement is made on something like a cobot’s cylindrical welding capabilities, the updated recipe is uploaded to the cloud, and all BotX Welders are updated, often unbeknownst to fabricators not involved with the initial improvement request.

Lewis said the cobots have improved the quality of welded parts because of their ability to deliver the same welds repeatedly, part after part. It even makes welders’ contributions more valuable when they are needed.

“We can have a welder acting as the operator, and he can take more time to look at the parts welded by the robots,” Lewis said. “He can look for porosity and see if there are concave or convex welds.”

PMI has about 50 different parts stored in the control software. To switch between stored jobs, an operator can use the app on a smartphone.

The addition of the cobots to the welding area has been a good fit, Larson said. It’s allowed the company’s 14 certified welders to work on larger and more complex jobs that are, frankly, more engaging than applying a small weld repeatedly over a thousand-piece run. Also, when the cobots aren’t welding, PMI isn’t paying for their use. Cloud monitoring of the cobots notifies Hirebotics when welding is taking place and allows for 24/7 virtual support.

“We have read that the number of available workers between 18 and 65 is going to continue to go down over the next decade. So our assumption is that we’ll be fighting even harder for that labor pool as we go along,” Conard said. “The introduction of automation like this helps us become less dependent on trying to find the right people. We can still grow and offer additional capacity to our customers when needed.”

On the Level

PMI is a longtime supplier to the appliance industry. One of the reasons that it has been able to maintain those relationships over the years is that it has been responsive to industry trends.

In fact, that led to the acquisition of a used Pro-Eco tension leveler about two years ago. Over the past several years, appliance-makers have moved to thinner-gauge materials for the exterior of refrigerators and freezers because insulation has gotten much better. The thinner material, however, is not as forgiving as the thicker material that was used to make appliances a generation ago.

PMI already had built a reputation for coil processing with its 60-in. Cincinnati slitting line, 60-in. Herr-Voss cut-to-length line, and embossing capabilities. The new leveler line, which came online in August 2019, is meant to add another dimension to the company’s coil capabilities—particularly in material 0.030 in. and thinner.

“When the coil comes in, sometimes you’ll see the odd shaping as you try to run it. You’ll need to get it flat because you can see the edge wave or center buckle in the coil,” Larson said.

“Now we can take that coil and basically stretch it on the leveler line so that something like the edge wave goes away. Then you have a flat sheet.”

This line installation wasn’t a simple task. Not only did PMI personnel have to install the line, they were looking to customize the equipment for their own needs. They built the line’s feeder system, the edge trimmer, and added a coil-to-sheet modification for customers that might want to receive flat blanks from coils once deemed defective. (PMI also has coil-to-coil capabilities attached to the leveling line in case customers want to receive their newly leveled steel back in coils.)

“We hope now word gets out to the mills and service centers that they don’t need to go to the subprime market and lose half the value of their coils [if there are deformities in them],” Conard said. “We can revitalize the coils, getting the shape out of them. Then they have prime coils again. They don’t have to reject them.”

Getting It Done in Bloomer

PMI has a lot happening under its roof. Conard said customers really don’t grasp what the company can do until they see it with their own eyes: two significant coil processing lines; the new leveling line; the large coil bay; a railcar filled with coils waiting to be unloaded; stamping presses; automated welding; manual welding; a punching machine; and three laser cutting machines, one of which is a TRUMPF TruLaser 2030, a 4-kW solid-state laser that was put into service in the spring. When those customers actually do visit, they can grasp the possibilities.

That’s all that the company is asking for, according to Conard. It wants to show current and potential customers that it can be very cost-competitive because it has so much to offer. It may stop short of offering aquatic weed removal as part of its service offering, but PMI feels like it has made the investments in people and technology to be a best-price partner.

“That’s what we’re addressing. We’re looking at things to get customers’ overall costs lower,” Conard said.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Trending Articles

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

How laser and TIG welding coexist in the modern job shop

Robotic welding sets up small-batch manufacturer for future growth

Ultra Tool and Manufacturing adds 2D laser system

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,