Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Die Science: Stamping stainless steel (part II)

Part II: What to expect and how to react

- By Art Hedrick

- July 31, 2017

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Expect More Springback

Springback, also known as elastic recovery, is the result of the metal wanting to return to its original shape. Because stainless steel has inherently higher strengths and work- or strain-hardens more than plain low-carbon steel, you must overbend or overform the metal beyond the intended bend angle or shape. The amount of overbending is a judgment based on the grade of stainless steel , its hardens and thickness, and the geometry you want to achieve.

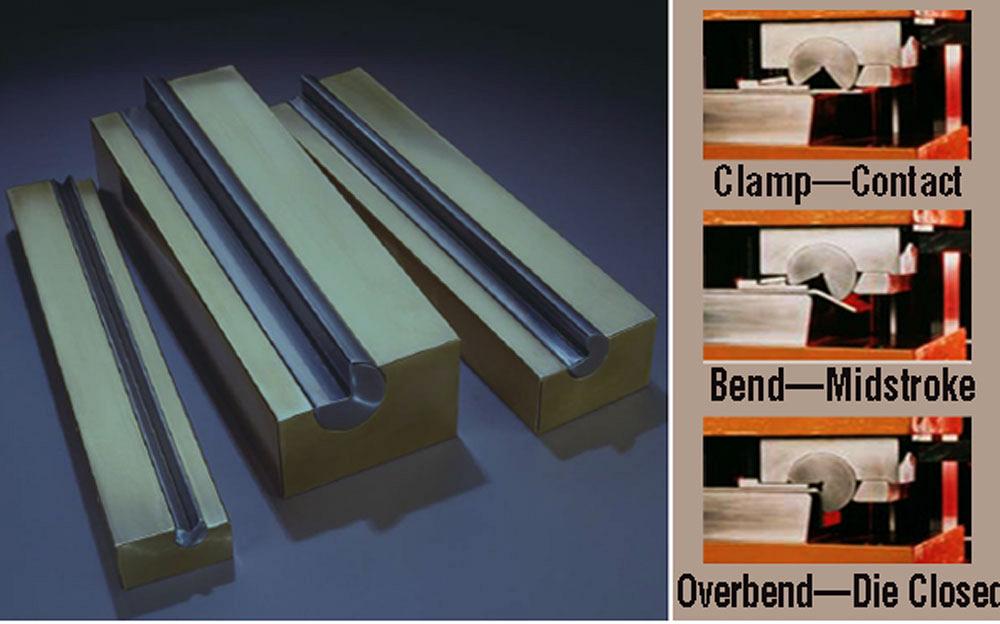

For straight-line bending, a rotary-style bender is recommended (see Figure 1 ). This type of bender allows you to make simple, accurate adjustments with respect to the bend angle. In addition, it requires much less force than other benders to create the bend. This is especially desirable when forming hardened or high-carbon martensitic grades of stainless.

When stretch forming or drawing stainless steel, try to stretch as much surface area of your part as evenly as possible. This will reduce the amount of springback.

Avoid Overworking the Metal

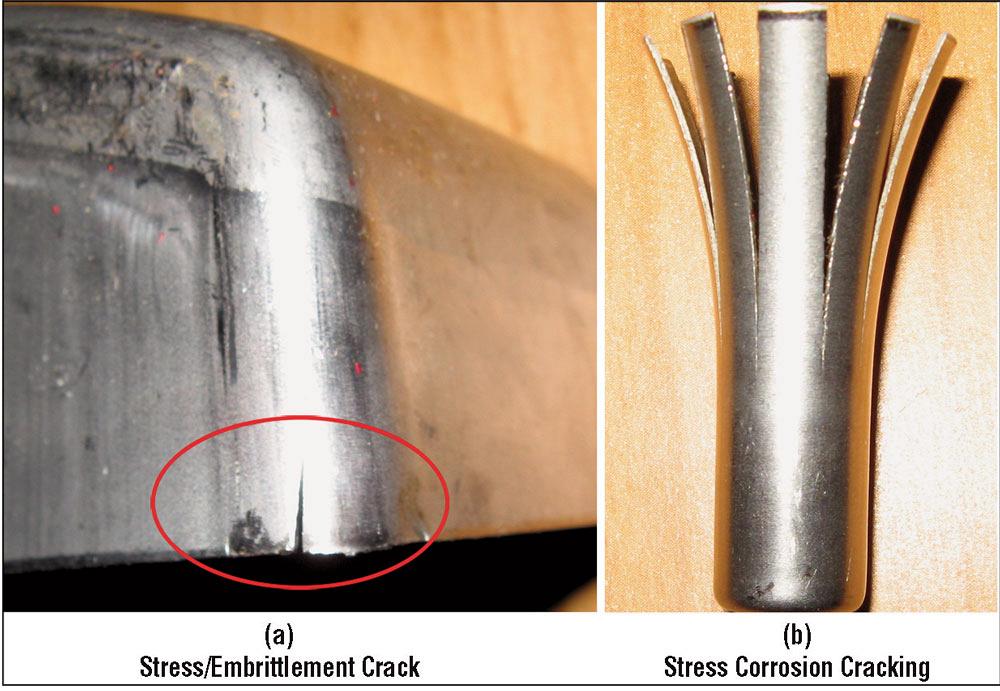

Because stainless steel often work hardens much more than low-carbon steel does, it is very susceptible to compression or stress cracking. Both of these are the results of severe cold working. Certain grades of stainless may require annealing between forming stations to soften the steel and allow it to be re-formed as needed.

Figure 2a shows a typical stress crack. In addition, certain types of stainless steel may be susceptible to stress corrosion cracking (see Figure 2b ). This is a combination of work hardening and corrosion often caused by chlorides in the lubricant.Expect Greater Cutting and Forming Forces

Stainless steel typically has much greater tensile and yield strengths than low-carbon steel does. For this reason, it is critical that you choose a press that has adequate force available to perform the work.

A good rule of thumb is to double the force needed for plain low-carbon steel. Also, if you are drawing, double the blank holder force.

Slow Down

Figure 1

A rotary-style bender is suitable for

straight-line bending. Photo courtesy of

Danly Corp., Miami, Fla.

As a rule, the more slowly you form stainless steel, the better. For example, trying to deep-draw a 3-inch-diameter cup to a depth of 2.5 in. using a press with a ram speed of 70 feet per minute (FPM) will prove to be futile.

Avoid using fast blanking presses when forming stainless steel. Hydraulic presses are the best for deep drawing stainless steel. Depending on the stainless that you are forming, try not to exceed a maximum forming speed of 40 FPM.

Select the Right Lubricant

Because stainless steel often has very smooth surface topography, it is sometimes necessary to add wetting agents to the lubricant. For deep drawing cosmetically fussy parts such as kitchen sinks, poly film or thin-film barrier lubricants often are used. These thin sheets of plastic both lubricate and protect the surface (see Figure 3 ).

In deep-drawing applications, it is often necessary to use lubricants containing chlorine or sulfur. These heat-activated additives help to reduce the friction when the forming temperature get extreme. For deep drawing, lubricants such as mineral oil and motor oil will most likely prove to be useless because of their low working temperatures.

Select the Right Tool Steel

Stainless steel by its chemistry is very abrasive because it contains chromium. Hard chrome often is used to coat large stamping dies such as those for body panels. This coating of chrome gives the die greater resistance to both abrasive and adhesive wear.

When selecting a tool steel for forming stainless, use steel that has both good toughness and wear resistance. Whenever possible, avoid using conventional D-2 tool steel— not because of its lack of toughness or wear resistance, but because of its high chromium content. The high chrome in the stainless will interface with the chrome in the D-2, often resulting in cold welding or surface-to-surface migration. This will cause the tool steel to “pick up” some of the stainless sheet, you can solve the problem by coating the tool with physical vapor deposition (PVD) or chemical vapor disposition (CVD) coatings.

A great material to use for forming stainless steel is aluminum bronze, because it is completely dissimilar to stainless (see Figure 4 ). It often is used to make wear plates for cams and slides, as well as heels and thrust blocks. When choosing the hardness of aluminum bronze, keep in mind that harder grades might crack under severe shock load.

When using conventional tool steels and whenever feasible, use powdered metal (PM) grades such as the CPM® or vanadium grades, because they have much greater toughness and wear resistance than conventional tool steel grades. For severe metal forming and cutting operations, it might be necessary to coat the tool steel too. Coatings reduce the friction between the stainless steel work material and the forming punches. They also often add a thin coat of high-wear carbide to the forming punches. Solid carbide is great for forming stainless steel, but because of its poor shock resistance, it often is a poor candidate in operations undergoing a great deal of impact shock.

Figure 2

Stainless steel can be susceptible to stress cracking (a) and stress corrosion cracking (b).

Photo courtesy of Ready Technologies Inc., Dayton, Ohio.

Use Bigger Cutting Clearances

In most cases, cutting clearances are from 12 percent to 15 percent preside for soft grades and up to 20 percent for full hard grades. Generally speaking, the harder the metal, the bigger the cutting clearance.

Stainless steel is not necessarily harder to form and cut than plain carbon steel, but it is different. Pay careful attention to the type, grade, and hardness of the stainless steel than you are using. Understanding these important differences is the key.

Until next time… Best of luck!

About the Author

Art Hedrick

10855 Simpson Drive West Private

Greenville, MI 48838

616-894-6855

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,