Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Die Science: The big-bang theory: The causes of die crashes

- By Art Hedrick

- August 7, 2017

- Article

- Bending and Forming

One attendee told me that his company runs high-speed progressive dies at nearly 1,000 strokes per minute. I asked him, “When you run a die without electronic die protection at 1,000 strokes per minute, what happens in case of misfeed?” He said, “Its a bad deal,”” and promised to explain more the next day.

The following day he brought a photo to me and said, “Yesterday you asked me what happens to a high speed die when it is misfed. Well, you’re looking at it! Yep, it turns to ‘die dust” (see Figure 1 ).

Don’t get me wrong— not all die crashes are this bad. Believe it or not, some are worse!

I had visited hundreds of die and stamping shops all over the world, and it seems as though each toolroom has a special archive of munched, crushed, flattened, and bent tools and die components. I had seen everything from crushed dowels, bent Allen wrenches, and flattened micrometers to a mangled 24-inch digital height gauge. Some shops even showcase their broken tools as training tools for new hires.

Human Error

It’s a simple fact: Being a good press operator requires a great deal of self-discipline. It can be easy for press operator to lose their focus on the mundane task at hand—and that can lead to double-loaded and misgauged dies—and possibly a crash.

Here are two suggestions to help prevent these problems:

1.Educate press operators about the fundamental of dies. Teach them what to look for in each of the die types. Make sure they understand the basics of how the press works. Even if you have implemented a sophisticated die protection system, nothing can take the place of a well-educated operator. Be sure to train them:

- Scrap removal—Are all slugs falling free?

- Part ejection—Are parts falling free? A drawn panel stuck in the top half of the die looks similar to the die cavity. Operators need to look for the blank edges and make sure that a part is not stuck in the top.

- Die sensors/protection—When are the sensors at fault? When is it a die problem?

- Ask for their opinions on ways to improve the operations that they are responsible for. You might be surprised at the creativity that results.

- Give them credit or rewards for good, effective ideas. Sometimes a simple thank you is all they are looking for.

- If possible, invite them to a meeting or two when the die is being designed, and allow them to give feedback with respect to process such as part ejection and scrap removal.

- All bolts securing the die in the press are tightened and secure.

- Feed pitch and progression are set correctly. Over feeding or underfeeding most likely will result in a misfeed and die damage.

- Placement of the die in the press. Placing the die at a far end of the press can offload the ram and cause shearing and other die damage.

- Trailing edge of the strip. Running the trailing edge of the strip through the die may result in half-cuts and half-forms.

- Shut height of the press is correct and not to low.

- No loose scrap is evident, especially when first starting the strip.

- When designing progressive dies, use pad balancers to prevent each pressure pad from tipping when the strip is not fully loaded into the die.

- Provide adequate die protection such as proximity switches ad metal sensors.

- Heel the die properly to adsorb excessive side thrust that may be generated during cutting and forming.

- Put large leads on rails for ease of stock entry.

Poor Setup Procedures

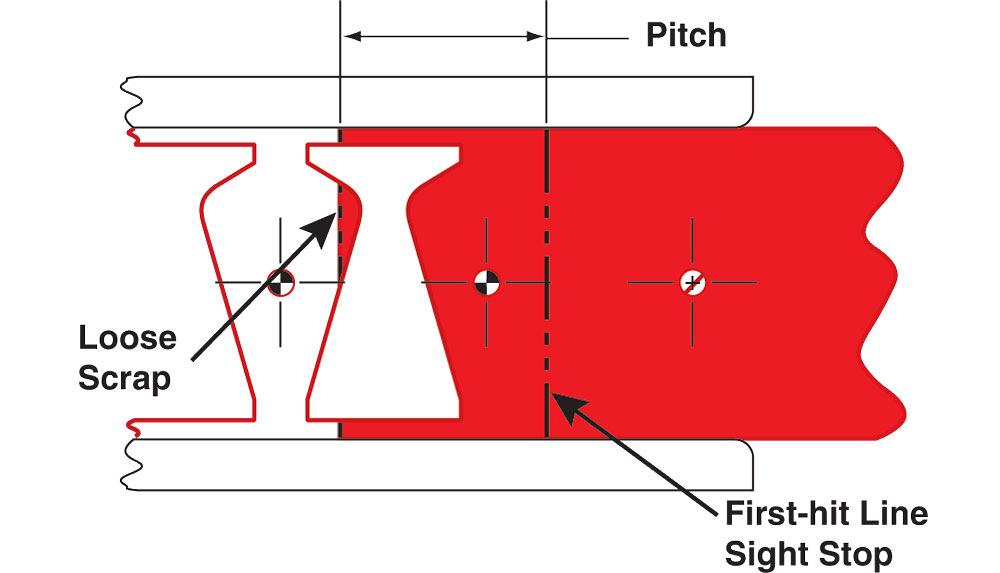

Statistically speaking, the strip is a very important step and requires careful attention. Starting the material in the wrong position can result in half-hits of half-forms. Unbalanced cutting or forming then can cause the upper and lower dies to misalign and shear, resulting in die damage.Also, incorrectly starting the material can leave lose scrap in the die. If the scrap is not removed, double metal results and is fed into the tool. This condition can cause severe die damage. A good die designer establishes a distinct first-hint line by placing a positive spring-loaded stop at this point, rather than a simple line with a “start strip here” message (see Figure 2 ).

Following are some items operators should double check during setup:

Die Design

Die designers must pay special attention to several important aspects during die design:With a little effort on the part of the die designer, builder, setup person, and operator, die crashes can be reduced. Of course, they can’t be eliminated, because as long as humans are involved in creating and running a stamping process, ether will be errors. To err is human, after all.

Until next time… Best of luck!

About the Author

Art Hedrick

10855 Simpson Drive West Private

Greenville, MI 48838

616-894-6855

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,