Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A symphony of metal fabrication

A smart shop layout can spur collaboration and make music

- By Tim Heston

- August 16, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

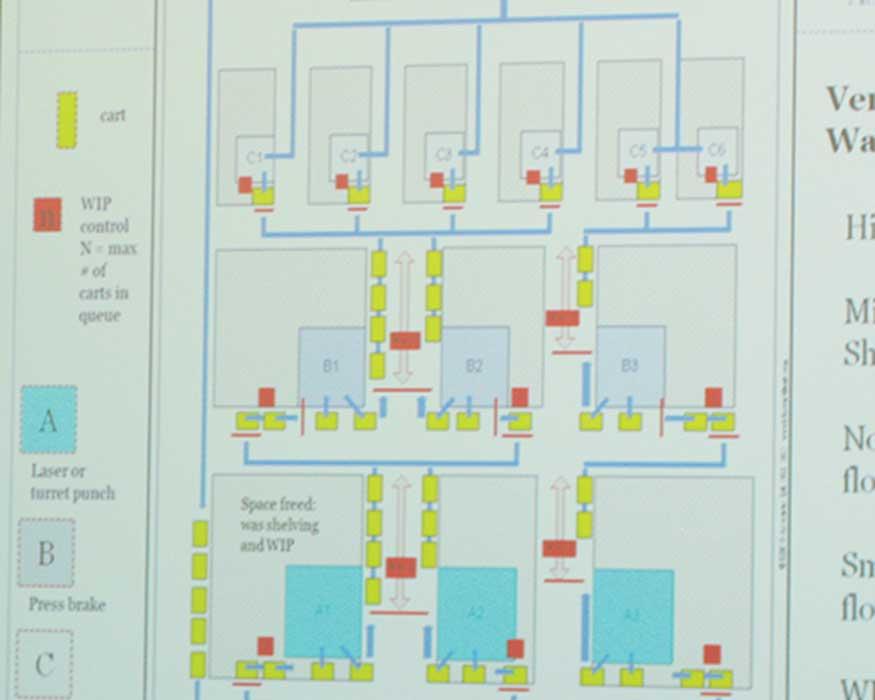

A portion of a slide, shown at a 2014 lean manufacturing conference organized by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, shows cutting (A), bending (B), and assembly (C) in a grid layout.

I have a confession: I’m a band geek. I made it through high school and college, zits and all, thanks to the support of my fellow band geeks. And I am no stranger to the phrase, “One time at band camp …” Yes—I was, and am, a proud nerd. It was about the collaboration. We all had to get to the same place at the same moment, in time and in tune (or try to, at least).

In music, you have the craft: scales, chords, breath control, bowing, phrasing. Then you have “the making” part—that is, playing music. And if someone is going to make music with someone else or within a larger group, that person needs to connect, collaborate, and get along.

Manufacturing is no different. There’s been a skilled labor problem in metal fabrication for as long as I can remember, and it’s a multifaceted problem. The craft can be taught, so the “skill” part is a straightforward fix. The collaboration and “getting along” part isn’t so straightforward. It can’t be taught, but a company can have structures and processes in place to bring collaboration to the fore.

Managers in custom fabrication encourage morning huddles on the floor. They encourage idea generation and continual collaboration, both during shifts and between shifts. So many fabricators have told me that they solved a lot of problems simply by getting people on one shift to talk to the next shift.

There’s good reason to do this. Custom metal fabrication has a challenging mix of needed craft and continual communication. And it’s easy not to communicate. Not only does the very nature of a multishift operation throw up hurdles to communication, but so does the nature of traditional batch manufacturing in process-based departments. Operators stand in front of the machine and silently churn away as they work toward their production goals.

Thing is, customers don’t care about how many parts per hour the laser or press brake department can make. They care about how quickly it can make parts. That’s what restructuring into value streams is all about, and it’s a thing of beauty when you see it in action. Consider Total Door Systems, a custom door manufacturer in Michigan that has achieved single-piece flow. You can see doors progress on the U-shaped production line, and you can see people collaborating to move jobs forward as efficiently and effectively as they can. The close proximity of different manufacturing processes does wonders for collaboration, and the entire layout itself seems to focus not on strokes or cuts per hour on this or that machine, but instead how fast products flow down the line.

This can work for product lines, even highly customized ones, but I’ve never seen such a production line in a conventional custom metal fabricator, which might process thousands of different parts with different routings every month. I’ve visited some shops that have been organized into fabrication cells, such as a laser or punch next to press brakes next to a hardware insertion press. And plenty have built multiprocess cells around one product or product family.

But I’ve never seen a custom fabricator organize everything in multiprocess cells that extend from raw stock to the finished product (though one may exist). A fabricator may have identified value streams, but look at the physical routings and you’ll see that jobs still follow a circuitous path.

“Is there a reason this couldn’t work?”

So asked the late Dick Kallage, a lean manufacturing consultant who was a columnist for this magazine for years. He asked the question at a conference in 2014 organized by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International. He proposed laying the entire plant out in a grid, with laser cutting and punching in the back row, deburring and forming in the second row, welding and assembly in the third row, etc.—creating what Kallage called “virtual cells.”

Being a music nerd, when I saw this, I thought about the symphony. Like the fab shop, the orchestra is separated into sections—violins, violas, trombone, trumpets—but these sections don’t make their best music in separate rooms. They all need to be on stage, sitting in specific places to ensure maximum blend and the best sound. With Kallage’s virtual cell proposal for the fab shop, I saw maximum effectiveness and the greatest throughput.

This arrangement allows parts to flow straight from one step to another, with only several cartfuls of work-in-process in between. It requires quick changeover and promotes single-piece, or at least single-sheet, flow, which is not an outlandish idea, considering the quick-changeover techniques and technologies in the market today.

The nature of metal fabrication demands that some processes, like welding, grinding, and powder coating, be separated by some distance, or at least a physical barrier, mainly because of the particulate those processes emit. And some machines tend to be monuments. These large shared resources (powder coating line, e-coating, plating tanks, heat-treat ovens) are difficult to move and expensive to duplicate.

Moreover, a fabricator is limited by the building it occupies, like old buildings chopped up into various rooms, artifacts of the days when splitting production operations into numerous process-based departments was thought to represent the utmost in efficiency. I’ve seen fabricators take great strides in building workarounds, like designated fork truck lanes and routes, to make the moving of material more predictable.

But if a fabricator moves into a new, open space, the world opens. With Kallage’s virtual cell layout or something similar, people can work closer than ever. This perhaps can broaden their perspective. Seeing parts flow around them, they can appreciate how their efforts—be it on the laser cutting machine, press brake, grinding, or anywhere else—fit into the whole. They’re not just producing notes on their instrument. They’re making music.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI