Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Big data wellspring for optimal flow in metal fabrication

Among fab shops in Northern Europe, the future of big data is now

- By Tim Heston

- November 3, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

Based in the Netherlands, 24/7 Tailor Steel’s cutting and bending annex (“customer paradise” in multiple languages is on the floor) has automated lasers with pick-and-place robots adjacent to six LVD ToolCell automatic-tool-change press brakes—all placed among living trees. The company is on pace to grow by 45 percent this year.

Ton Pasnagel pointed to a cart of aluminized steel, a material that can withstand significant heat and resist rusting—both important attributes for a gas and wood-burning stovemaker like Barbas-Bellfires nv, where Pasnagel is director of operations. The lacquering operation is the stovemaker’s current bottleneck, and the aluminized steel the company is testing wouldn’t require any lacquering whatsoever.

“Flow is the main driver here,” he said.

Pasnagel’s operation is in Bladel, the heart of the Dutch sheet metal industry. Drive the short distance from the highway to Barbas-Bellfires, and you pass by shops that collectively have more than 50 laser cutting machines. This area includes a plant owned by VDL, a European powerhouse that’s one of the largest sheet metal operations in the world.

It’s likely Pasnagel’s comment on flow would resonate with many of these operations, especially considering the lead-time demands that customers place on custom fabricators (or “subcontractors,” as the Europeans call them) in the Netherlands and nearby Belgium. Fabricators no longer talk in weeks. It’s now about turning things around within hours or days.

Flow was a pervasive theme during a tour for North American industry press, which LVD Strippit hosted in September. European fabricators ship one of this, a half dozen of that, with little or (usually) no finished-goods inventory to use as a safety net. A large finished-goods inventory is simply impractical, considering shops really don’t know what’s coming next.

Many tackling lean methods in metal fabrication talk about focusing on job flow. An idle machine may or may not be a concern, but a stalled job (for instance, sitting days between operations as work-in-process) is always a concern.

The shops on LVD’s tour have all scrutinized the big picture, the complete order-to-cash cycle. The most advanced among them have automated the entire front office. A customer clicks “order” on a web portal and the part is nested and sent to the laser, all within minutes.

In this world, machine speed really matters, as does everything in between, from automated order entry to automated guided vehicles (AGVs) that take orders from one operation to the next. This is the world of Industry 4.0, where machines and software communicate so that (ideally) everyone knows where every job and every part is at all times, building an ever-more-comprehensive and useful database—so-called “big data.” This is also the beginning the next step (what sources at LVD called Industry 4.1), where machines not only communicate, but also interpret, learn, and get better at what they do.

All these fancy terms really are just a means to an end, one exemplified by the fabricators on the press tour. In the end, it’s still all about flow.

Pulling Fire

Once upon a time it took Barbas-Bellfires six weeks to produce a stove, be it the gas or wood-burning variety (branded under the Barbas name). Today it takes a day to process an order and three days to fabricate and assemble it.

Primarily decorative, these stoves end up in homes in Europe, Canada, South Africa, and elsewhere. Most of the steel shell lies hidden under a façade built into the wall (see Figure 1), but this fact does not diminish the fabrication challenge.

Figure 1

On the left, Ton Pasnagel, Barbas-Bellfires’ director of operations, stands next to one of the company’s wood stoves. Most of the company’s products lie hidden behind facades, as with the gas stove on the right.

Until three years ago the organization purchased these sheet metal shells from custom fabricators in Eastern Europe. That strategy, managers found, created that six-week lead time. To shorten it they brought cutting, bending, and welding in-house—but they didn’t implement those processes in a typical way.

As the company brought in more fabrication operations, including LVD lasers and press brakes with laser-based angle measurement and automatic correction, Barbas-Bellfires ramped up its brand of continuous improvement. Managers began by using elements from quick-response manufacturing (QRM), an improvement method designed for high-product-mix operations (www.qrmcenter.org). Barbas-Bellfires certainly fits this description, with hundreds of different types of stoves departing the factory every week. Per the QRM philosophy, the company grouped these stoves into product families, 15 of them, then built workcells around them.

The final assembly cells show QRM in full force (see Figure 2). Workers designed them from start to finish, from the tool placement to the lift carts that hold the stove frames at a convenient height. Instead of being U-shaped, each cell is straight; they could be called assembly “lanes,” with each lane designed around specific product families. No one performs one operation over and over again. Instead, each person moves down the lane with the product, performing all tasks needed to complete assembly.

Because workers move from one station to the next, supervisors can see where the assembly operation stands. If one worker remains in a station for too long, everyone can see the problem as it’s happening and, if necessary, take corrective actions to help. Workers also decide the best sequence of stoves for maximum throughput.

Final assembly is the crux of the operation’s pull-system methodology, a key element of lean manufacturing. Downstream processes trigger, or pull, upstream operations into action. This includes the burner assembly lanes, which in turn pull from upstream processes, including lacquering, which (until tests are finalized on the aluminized steel) will likely remain the constraint operation.

Manual lacquering isn’t a pleasant job, which is why no one performs it more than two hours a day. It’s why cross training is so important. From a production perspective, cross training allows people to move to aid flow and boost job throughput. Performing different jobs throughout the day also helps employee morale. People are happier at work.

Barbas-Bellfires does not have separate cutting and bending departments (see Figure 3). Instead, parts flow directly from laser cutting to bending. Specifically, parts are removed from nests and go directly to one of several LVD Easy-Form® press brakes with laser-based, automatic angle measurement and correction. Workers scan bar codes on the cut blanks, and the control brings them through the bend sequence—with not a blueprint to be found around them.

The company does employ one highly experienced press brake operator who reads blueprints extensively and works on new product development. It’s not unusual to see that operator work directly with the company’s engineers, whose desks are right on the shop floor. As Pasnagel put it, “That is where the value is created, so that is where we need to be.”

He added, though, that he wouldn’t call the other people who bend parts on the press brakes “operators” in the traditional sense. They don’t read blueprints regularly, nor do they know the intricacies of bend allowances, deductions, sequences, and radius development. They can certainly climb the ladder and, if they wish, learn more about bending. And like everyone else in the plant, they monitor flow. If a process doesn’t “pull” work from an upstream process within a certain amount of time, people see it immediately, both on the floor and real-time metrics shown on flatscreens throughout the plant. This helps people correct problems before they snowball into larger ones.

For most of Barbas-Bellfires’ work, the entire build cycle takes only four days: one day in order processing, one day in cutting and bending, one day in welding, and one day (yes, just one day) from lacquering through final assembly and shipping.

Figure 2

Stoves move down an assembly cell, or lane, that’s dedicated to a product family. One person moves down the line with the stove, completing the final assembly from start to finish.

All this creates an environment that’s evidently attracting talent—a true feat, considering the area’s incredibly low unemployment of less than 3 percent. A few weeks before the press visit, Barbas-Bellfires hosted an open house for interested applicants.

“I would have been happy if we had 20 or 30 people. But we got more than 100 visitors and more than 60 people who are very interested in working here,” Pasnagel said. “It helps to have a good factory.”

Improvement Never Stops

Johan Miermans is not one to think things are good enough as they are (see Figure 4). Last year he became CEO of Vanderscheuren outside Diksmuide, in the Flemish province of West Flanders. In May 2016 KeBek, an investor group, purchased a majority share of a family business that had been run by two brothers, Rik and Luc Vanderscheuren, for decades—and run rather well, as evident by strong financials. Miermans did not reveal specifics on the record, but he did say that the balance sheet’s health was well above the industry average.

It’s a contract operation where repeat work dominates. The company has made a name for itself for its reliability. Miermans described one major customer that makes textile machines. The customer produces about 50 machines a day, and Vanderscheuren produces subassemblies for them—with no finished-goods inventory buffer. “If we stop producing today, they will not make any machines tomorrow,” he said.

The 12.1-million-euro company invests 1 million euro annually in capital equipment. And it shows on the shop floor. In fact, Vanderscheuren is really two shops under one company. One facility houses automated laser systems, press brakes, and welding, while another factory across the street focuses on machining—not an operation that merely supports the sheet metal work, but a full-blown machine shop with about 30 CNC turning lathes and another 30 milling machines.

The company has invested in LVD laser cutting machines for years. A laser from 1989 still produces the occasional blank when needed. But today all of the half-dozen LVD laser cutting machines in regular use, including a new 6-kW fiber laser capable of cutting up to 1-in. plate, run fully automated. Only a few operators manage all of them.

Sheets are loaded, material is cut (with various jobs on one sheet), and parts are offloaded. Specialized cut programs “chop” the skeleton to make material removal easier. Material handlers don’t have to shake out microtabbed parts but instead “peel away” the nest from one edge to the other.

Across the street in the machine shop, a square tube sits in a fixture with several drilled and milled holes and pockets (see Figure 5). This square tube doubles as both a structural support and a functional part of a textile machine, and it exemplifies Vanderscheuren’s competitive position.

The company co-engineered this product with its customer, and that design is evolving. At this writing, the tube is cut with a band saw, then milled in specially designed machining centers with beds long enough to accommodate the product.

But could this tube be cut with a laser? Also, its routing isn’t ideal; some operations are performed at the factory across the street. In fact, Miermans pointed to various product flow issues throughout the facilities—between welding and cutting, between certain milling and turning operations, and elsewhere—that he and other company leaders intend to resolve and improve upon in the coming years.

Figure 3

Cut steel destined for a gas stove is staged for the next process (on left). The automated laser cutting system feeds the adjacent press brakes (on the right).

What makes the improvement initiative unusual is that it’s not happening during a time of crisis. The company is busier than ever, and, again, the balance sheet is very healthy. But according to Miermans, this makes it the best time to tackle improvement.

“Most start improving in a crisis. We don’t have that problem, but there is a sense of urgency. If you get close to a crisis and try to improve, it may be too late.”

Thinking Anew

At LVD headquarters and customer experience center in Gullegem, Belgium, Kurt Debbaut, product manager of CADMAN® software, pointed to a series of colored boxes, a chart that captures the essence of flow. Jobs released to the floor have already been verified to be correct, their forming requirements simulated based on the actual tools available on the floor.

Orange boxes show a job that’s in progress at various stages of production, from the order release through bending. Red boxes show jobs that have issues (material problems, etc.), blue boxes show jobs that are in queue, and green boxes show that a job has been complete.

Intelligence provided by CADMAN-Job software, the chart gives a snapshot of a fabricator’s current state. The red boxes reveal distinct problems, but the blue boxes also reveal problems that might have gone unnoticed. If a job sits in queue (the blue box) for days on end as WIP, the shop has a problem with flow.

WIP is perhaps the greatest drain on throughput in modern metal fabrication. A part may have only a few hours of “touch time,” when the part is loaded, cut or bent, and unloaded, but the queue time between jobs can sometimes last days.

Broaden the view beyond cutting and bending to include order processing upstream, assembly and shipping downstream, and it’s easy to understand why it takes jobs weeks instead of hours or days to make it through the shop. A fabricator needs some WIP to mitigate inherent process variabilities of a high-product-mix operation.

But why exactly do fabricators have such variability? Where does it come from? You have 3-D CAD, business software like enterprise resource planning (ERP), postprocessing of files to cutting and bending, even adaptive bending that can adjust for different sheet thicknesses, hardnesses, and grain directions. Connect the dots between digital information and machinery and, in theory, the variation plummets, even in the most high-product-mix environments.

Carel van Sorgen has connected the dots.

Van Sorgen has been around sheet metal for most of his life, pioneering the use of CNC machinery and laser cutting in the 1970s (see Figure 6). For years he had ideas about streamlining the entire order-to-delivery process through software. His vision included a lot of the ideas behind Industry 4.0 years before the term had been created, and for years technology had yet to catch up. Industry 4.0, big data, and all the rest are difficult to accomplish with dial-up internet access.

That all changed by 2007 when he launched 24/7 Tailor Steel in Varsseveld, a Dutch town not far from the German border. It started small but grew extraordinarily quickly. Today the company is expecting to grow by 45 percent, no small feat for a fabricator that employs 250 people in two plants. 24/7 ended 2016 with more than 50 million euros in sales, and on average the company gains 19 new customers a day. All told, the fabricator has about 5,000 customers. Most start with small quantities—one of this, a half dozen of that—but as the relationship matures, quantities grow.

Figure 4

Rik Vanderscheuren (on left) took over Vanderscheuren nv with his brother Luc in 1989. In 2016 the investor group KeBek became majority shareholders and brought on Johan Miermans (on right) as CEO.

“By 2020 we plan to double our [annual sales] and employ 550 people,” van Sorgen said. “And this is only the beginning. Instead of additional machines, we are now thinking in additional plants.”

Most fab shop managers dealing with such astronomical growth wouldn’t have time to talk to reporters, mainly because they’d be dealing with a chaotic shop floor. But 24/7 Tailor Steel isn’t chaotic. Everything just flows.

The fabricator doesn’t have traditional salespeople, nor does it employ an army of estimators and production planners. It instead employs just two people in the front office who handle customer service calls and manage certain credit checks. Everything else happens automatically online.

Here’s how it works. A customer visits a web-based platform called Sophia, short for Sophisticated Intelligent Analyzer. “Sophia also happens to be the name of my oldest daughter,” van Sorgen said.

Customers upload a CAD drawing, be it cut flat or bent, choose a material grade and thickness, then choose a quantity and ship date. The customer also chooses whether they can accept deliveries early. If the file incorporates multiple pieces or an entire assembly, the software splits it into its component parts. If the parts require painting or welding, 24/7 has partnerships with nearby suppliers, so those elements can be incorporated into the quote as well.

The software even checks for manufacturability. For instance, it checks for tooling problems or collisions in the bend sequence. In the not-too-distant future, the company hopes to incorporate bend simulation videos to show customers just how a part will be bent; or, if the part can’t be bent, the simulation will show why. If a part will be powder coated at the local supplier, software even simulates how the part will hang to ensure the supplier’s robotized powder coating system provides adequate, consistent coverage.

Within minutes the customer has a quote in hand. That quote is good for 48 hours. If it’s not accepted at that point, it’s saved in the system, where the customer can retrieve it, click once, and receive another quote based on current material prices.

When the customer accepts the quote, the job is nested, and sent to one of the company’s flat cutting lasers (22 of them across two plants), or one tube laser, which is in the company’s plant in Germany.

Employees refer to screens that show which machines are cutting what, in real time. In this sense, they don’t operate machines; they manage processes. “The screen shows the machine, the process it’s undergoing, the fact it’s running part two and three out of a total of eight parts [in a nest],” van Sorgen said. “And we keep track. The moment something does not go well, we can see which shift it took place and what material and job it was cutting, so we can then make decisions.”

Within a few days, or sometimes hours, the completed order goes onto the delivery truck. The company’s on-time delivery rate is approaching 99.9 percent. And true to the company’s name, the fabricator runs three shifts, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, even on Christmas.

Although the shop floor has eye-opening laser capacity, it has no large automated storage and retrieval system. “Those need a lot of space and you can put a lot of material in it,” van Sorgen said. “For us, that adds costs.”

Figure 5

These square tubes, structural members of a textile machine that double as a functional part , are cut, machined, and drilled in Vanderscheuren’s machine shop.

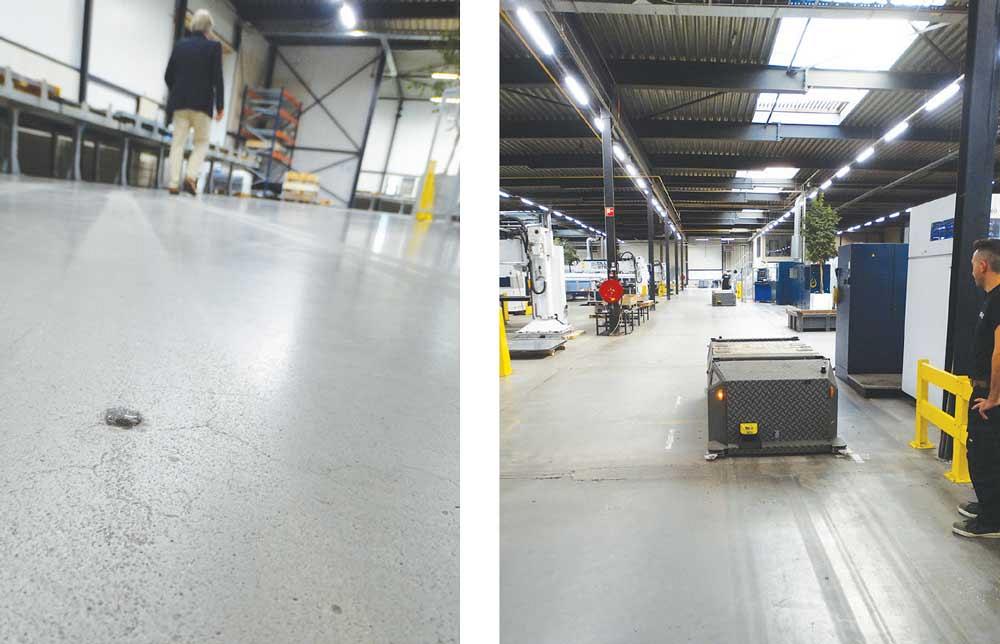

But material handling still is automated, thanks to AGVs (see Figure 7). Shallow stacks of different sheets line the factory perimeter—just 36 hours’ worth of raw stock. The only day that may require a little extra is Dec. 24, just because material suppliers don’t deliver on Christmas.

Supplier reliability is critical. “Without it, our whole system just doesn’t work,” van Sorgen said, adding that for this reason supplier performance is monitored continually. Delivery performance trumps price, always.

Sheets are moved to the AGVs, which then ride on a path lined with small magnets several meters apart. The magnets, combined with software, keep the AGVs on the right path, maneuvering around other AGVs and delivering material to the right machine at the right time.

Workers don’t “operate” the lasers in the traditional sense. They instead manage the process, ensuring the right material is loaded at the right time and retrieving parts, and observing the process to ensure cut quality is maintained. If parts require nothing but cutting, employees place them in boxes or (for very small quantities) in envelopes, staged and ready with the mailing label or delivery slip.

If the part requires bending, it is moved to the forming area to one of six (soon to be eight) LVD ToolCell press brakes, which change tools automatically. The operator scans a job into the control, and the ToolCell takes over, swapping out punches and dies as the material is staged for bending. Following a 3-D bending simulation on the controller, the operator bends the job.

No laser on the plant floor is more than three and a half years old. As van Sorgen explained, the state of the art in lasers is progressing so rapidly that replacing machines makes business sense. And by turning its inventory so rapidly and efficiently, the company has the cash to reinvest.

Although van Sorgen said he does source painting and welding to local suppliers, he has no plans to bring those processes in-house. The same applies to assembly. This strategy, he explained, gives the company focus.

He used a bakery analogy. Sure, a person can bake bread in the home, but it takes a lot of time and resources. Getting it hot and fresh from the bakery takes less time and, if you go to the right bakery, gives you better quality when you want it. The same thing applies to cut and bent parts from 24/7 Tailor Steel.

The Future Is Now

LVD opened its Experience Center (or XP Center) in April 2017. It greatly expanded its existing showroom. Past the modern glass entryway sits the latest machinery, including the Phoenix fiber laser with material handling automation, and with a cutting head with mechanisms that change the beam diameter in the focusing optics to achieve the optimal focal point in both thin and thick material.

The showroom has an LVD laser tube cutting machine and a Strippit PX-series punching machine with its bending tool and rotating V die (picture a rotating Pac-Man), with the ability to form high flanges.

The showroom also has a plethora of bending equipment, including the ToolCell automatic-tool-change press brake (see Figure 8).

It also has a small version (which is still rather large) of its Synchro-Form press brake, tailored for large workpieces and incremental (bump) bending of large radii (see Figure 9). Angle measurement and correction systems, including LVD’s laser-based Easy-Form, can measure bend angles down to a certain point. But in most cases, it can’t handle incremental bending; each bump bends the material a minute amount, an angle too small for the laser to detect.

Figure 6

Carel van Sorgen, president of 24/7 Tailor Steel, has been in the sheet metal industry most of his life. His father launched a sheet metal shop after World War II.

The Synchro-Form, using a combination of cameras and lasers, can detect these radii and adjusts the program to suit. If in the first radius bend the springback is a little more than expected, it then makes corrections for all subsequent bends. The cameras are enclosed in support arms that manipulate the workpiece throughout the bending cycle.

These machines certainly stand out, but so does something else: “To be honest, when people come here, they expect to spend the day seeing machines. But then they find they spend most of their day learning about software.”

So said Matt Fowles, LVD’s group marketing manager. The company’s CADMAN suite has evolved to include not only punch and laser nesting, bend programming and simulation, but also production control (CADMAN-Job), which can schedule the workload in the shop and reveal in real-time how jobs are flowing.

“LVD’s CADMAN ‘optimized process flow’ approach also has a sort-and-label function after cutting,” Fowles added. Operators sorting jobs use tablets (Touch-i4) to sign off on part quality and route parts correctly to the next operation.

All fabricators on the press tour use CADMAN to some degree. Some also have developed their own systems, like 24/7’s all-encompassing Sophia, that work together with CADMAN.

“Big data is the future.”

So said van Sorgen, standing under a tree, one of several dozen benefiting from the numerous skylights in the ceiling. “This is the second year we’ve had trees,” van Sorgen said. “You wouldn’t believe how cold and uninviting this place is without them. Trees make us happy.”

Take the bright, tree-lined factory floor, add a sleek breakroom with ample food and great Dutch coffee, and you get an extraordinarily pleasant work environment.

But it wouldn’t be pleasant if everything weren’t under control. Flat screens on either side of the breakroom show a map with several dots on them—the last delivery trucks of the day making their final stops. Van Sorgen calls 24/7’s drivers “ambassadors.” They deliver products and talk with customers about current or future jobs, or anything else. People in the breakroom can see where they are. Thanks to software and big data, they know the status of just about everything.

Big data really is the future. Considering what fabricators around the world are accomplishing, the future is now.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI