Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How character shapes leaders in the metal fabrication shop

The org chart doesn’t define leaders; one’s influence does in manufacturing

- By Tim Heston

- December 13, 2022

- Article

- Shop Management

Ask managers in metal fabrication about their chief challenge, and without hesitation most talk at length about the skilled labor shortage. Ask them about what kind of people their shops need, and again, without hesitation, they talk about work ethic. Ask them to describe what they mean by that, and you soon realize that most shop owners and managers aren’t talking about people having any particular skill. They can teach the skills. The real problem is finding people who work well with others and are eager to learn.

What began as a conversation about skill and competency—knowing the difference between air forming and bottoming on the press brake, monitoring tool utilization on the punch, or the best technique for a challenging out-of-position weld—ends up being a conversation about character.

“A company culture is nothing more than the collective character of an organization.”

That was Mack Story of Blue Collar Leadership®, a Sharpsburg, Ga.-based consultancy that takes an unusual approach to leadership training. Such training often focuses on, well, company managers. Visit any leadership seminar and you probably won’t see too many people there from the front lines—those who actually do the work. As its name suggests, Blue Collar Leadership doesn’t take this approach. To explain, Mack borrowed from John C. Maxwell. “Leadership is influence. Nothing more, nothing less.”

Ria Story, his wife and business partner, finished his thought. “You manage things and processes. You lead and influence people.” She added that although the org chart identifies managers, it doesn’t identify leaders. No matter a person’s level of formal authority, anyone can lead.

Such influence fosters connection, which helps people develop and tap into the values that propel them forward—that is, their character.

‘Go Fix it’

Those on the front line might see a company mission statement posted on the wall, sit in an all-hands meeting and listen to the CEO talk about company values and culture, nod quietly, then head back to their workstation. Well, they think, that was a waste of time.

Why does the CEO’s message fall flat? Its substance might have lacked detail or any useful takeaway, but the root cause of audience apathy likely isn’t the message itself; it’s the messenger’s lack of connection. Because the CEO isn’t connecting, he or she isn’t influencing or leading. The CEO is stuck in manager mode, opining about shared values and telling everyone to think about them as they work. As Mack and Ria have said in their presentations, leadership doesn’t work like that.

“When we give presentations, we share stories,” Mack said. “We’re not presenting from a place of perfection. We’re real people. For instance, I tell people where I come from. I was a frontline operator. I ran a shear and broaching machine, and I remember going home with my clothes soaked in oil, even my underwear. That’s where I come from.”

At one large manufacturer, Mack worked his way up to become continuous improvement manager, where he worked with a plant manager that forever changed his view on manufacturing leadership. That manager arrived when the plant was struggling and losing money.

Mack and Ria Story of Blue Collar Leadership don’t focus on the org chart or who manages whom. They focus on the influence of leadership. Images: Blue Collar Leadership

“About a week after he arrived, he pulled me asked, ‘Where do we keep the gloves?’ I took him to the cabinet, where he pulled about eight pairs. He then went to every department manager at the plant, got them out of their offices, and went out to the production floor.

“He then stopped production and called all the operator leads over,” Mack continued. “He told them, ‘We’re going to operate your equipment for a few hours. We want you to team up with one of us on the leadership team. Get to know them, don’t let us hurt ourselves, and don’t let us tear up the equipment. We want you to look over our shoulders and teach us how to do your jobs. Also, whatever you all think the worst job here is, give that to me.’”

The most important part of this story occurred in a conference room later that afternoon. As Mack recalled, “He went to the whiteboard and said, ‘Tell me about the problems you saw out there, everything people are struggling with.’ He wrote those ideas on the board until everyone was silent. ‘Nothing else?’ He walked over to the door. ‘Go fix it.’ And he walked out of the room. I immediately thought, ‘Oh, I like this guy. This guy isn’t working off of spreadsheets. He’s working off of reality.’ That’s the way he led, and he unleashed our potential. Within three years, we went from negative 3% gross margin to a positive gross margin of 35%. We didn’t lay anyone off. We just had a new leader, a leader with true character.”

The plant manager influenced people in a positive way because he built trust, not with empty rhetoric but with action. He broke down silos, including the largest—the one between the shop and the office.

“He also had the humility to know when to follow, admit he didn’t know everything about what people were doing, and he wanted to learn,” Mack said. “The people closest to the problem, those on the front line, usually know the most about a problem. And most of the time they’re not even asked about the problem.”

Such humility also shows respect for the power frontline people have, especially when it comes to managing through change. Consider a fabricator looking to implement a machine monitoring program to track green-light time. Such machine connection has become integral to modern manufacturers marching toward the ideals set by Industry 4.0.

Say this happens within a company where managers connect with employees and everyone exhibits high character. With machines connected and jobs tracked, software reveals previously hidden bottlenecks, after which a data analytics team parses the data and starts conversations—not with fellow managers but with frontline people who, again, actually do the work.

In this case, these workers (along with everyone else) respect managers and the overall company mission. The place isn’t perfect—no company is—but most people genuinely like and respect one another. They’re also not entrenched in silos, and everyone’s working toward the same goal. Data from those connected machines spurs kaizen events where everyone from across the organization—including operators and others on the front line—dissect the information and brainstorm potential solutions.

Now consider the same Industry 4.0 initiative in a shop without leaders who connect and influence, but instead where managers dictate and direct. Workers see machine monitoring as Big Brother, yet another example of management’s distrust. They look at a dashboard, and instead of thinking about opportunities for improvement, they shake their head in frustration. They have no idea what we have to deal with here.

“If your frontline people want the new initiative to succeed, it’s likely to succeed,” Ria said. “If they want it to fail, they have the power to make it fail.”

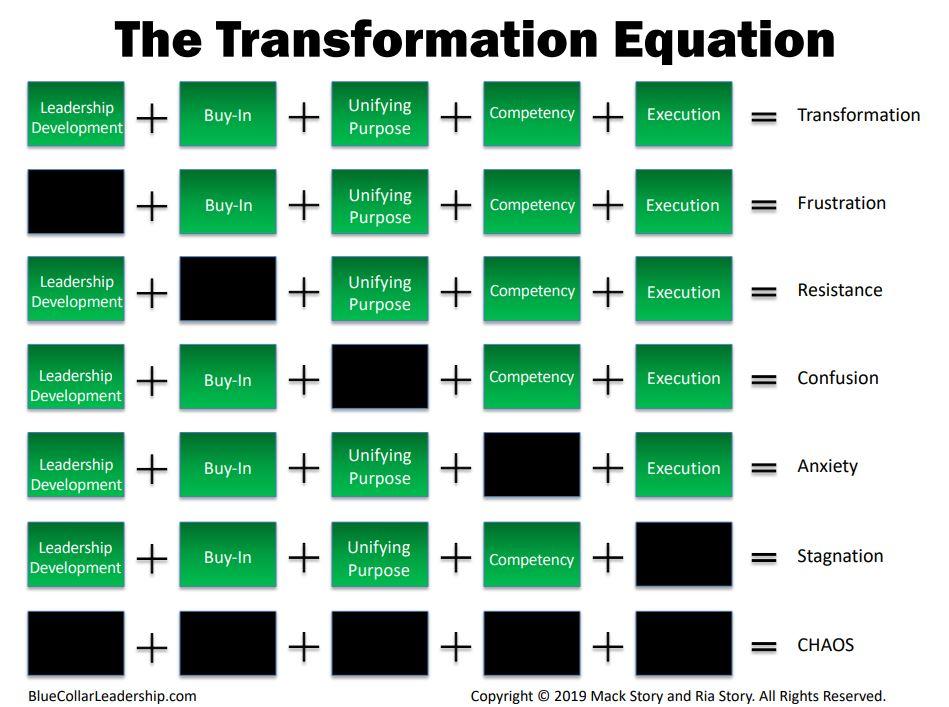

Transformation requires leadership development, buy-in, unifying purpose, competency, and execution. If one is missing, transformation falls apart.

They’ll find a way to circumvent data collection or somehow game the system. And even if they don’t, their lack of buy-in will act like a ball and chain on those few who want to push the initiative forward.

As Mack put it, “When leadership is missing, you get frustration. When buy-in is missing, you get resistance. When unified purpose is missing, you get confusion. When competency is missing, you get anxiety. When execution is missing, you get stagnation. When it’s all missing, you get chaos.”

The Storys call this the transformation equation: Leadership Development + Buy-in + Unifying Purpose + Competency + Execution = Transformation. Miss one element, and the transformation falls apart.

Investing in Character

“Employees are hired for what they know but fired for who they are,” Ria said, adding that the performance issues leading to that firing almost always have to do with character.

This circles back to metal fabrication’s perennial labor challenge. Manufacturers know how to invest in competency, with job shadowing, apprenticeships, and in-house training. But what about character?

“You can’t train for character,” Ria said. “But you can help an individual grow.”

Ultimately, it’s about personal transformation—and there’s no shortage of material. Employees can read books, listen to podcasts. Some of it might miss the mark, others might strike a chord. The trick, the Storys said, is not to ignore character development. Yes, it can’t be “taught” in the traditional sense, but a leader who connects with employees can help them develop it on their own.

“It comes down to moving beyond communication and actually making a connection,” Ria said. “The connection is about motivation, inspiration, and transformation.”

A big part of making that connection, Mack said, involves honesty—a big sticking point in an industry with a history of mass layoffs. And Mack can relate. He worked at Dana Corp. for a year before being downsized. He moved on to other manufacturers before starting lean manufacturing consulting work in 2008. At that point, he picked up a copy of Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. The prose hit a chord, and he kept reading.

“No one had ever introduced me to that type of content,” he recalled. “In fact, no leader I ever worked with had invested in this kind of content. It really resonated with me.”

Mack and Ria Story have spoken at events across the country, including FABTECH, held this year in Atlanta Nov. 8-10.

Thus began his personal development. Boiled down to its essence, Mack could have followed two paths. He could have continued to wallow in resentment about the layoff, the lack of leadership, and broken promises. He could have kept an iron grip on mistrust and trudge sardonically through the rest of his working life. Or he could flip his perspective and take responsibility for his life’s path.

“Taking more responsibility is about leading yourself,” Mack said. “What do you sell your employer when you come into work? You’re selling your experience, and that includes your character and your competency. That’s what you get paid for. And you own it. You take it home with you at night, and you can bring it in with you the next morning.”

People who take responsibility feed their character and competency, which builds the experience. “And you don’t need to be given responsibility,” Mack said. “Just take it. And one way to take it is to start sharing ideas about process improvement. You’re working for yourself.

“If I don’t like the boss, I don’t want to help the boss look good,” Mack continued. “That’s a natural feeling, but again, I’m working for myself. And if I’m doing that, I don’t want to make the boss look bad. If I make the boss look bad, I’ll look worse, especially when it comes to character. So, I want to make the boss look good whether I like the boss or not.”

Taking responsibility regardless of the environment—even amid a dysfunctional team—builds more experience to sell. “And you don’t need to sell that experience to the same person,” Mack said. “You can go to another company and sell your experience there.”

That’s unusual advice from a leadership consultant, but it fits within Blue Collar Leadership’s principal message: Leadership isn’t management. Anyone can be a leader no matter where they are on the org chart. Leading is about influencing and connecting with others, and if one’s character and competency doesn’t connect with a certain organization, they’re free to sell that character and competency elsewhere.

At the same time, those with character and competency are less likely to lose their job in the first place. “It’s about looking at yourself in the mirror,” Mack said. “Faced with change, high-impact people shine, low-impact people whine. Facing opportunity, who do you think will be promoted? Facing an economic downturn, who do you think will be let go first?”

Character, Competency, and Automation

High turnover happens at companies full of managers but bereft of leaders. “People buy in to the leader before they buy in to the leader’s vision,” Ria said. “Many managers aren’t positioned to lead people through change, because they’re used to just telling people what to do.”

This do-what-I-say, top-down style of management complicates something that hasn’t left manufacturing since the industrial evolution: technological change. In metal fabrication in particular, many choose to upgrade and automate because they can’t find the skill they need. And even if they could, modern machines simply outproduce their older counterparts. Quite often, a fabricator simply can’t compete without adopting new technology. That said, adopting the latest technology in a do-what-I-say environment could create a fabricator with a few knowledgeable people in a machine programming department sending work to a shop full of button-pushers. Automation enables disengaged people to produce, a situation that opens the door to all sorts of trouble.

“Even in an automated world, the people side doesn’t change,” Mack said. “I’ve got to interact with my boss. I’ve got to support people, their safety, and product quality. The equipment operation side has become easier. Most of the problems still relate to culture.”

Operators might not need to know G code or work bend calculations by hand, but there’s more to metal fabrication than bending the workpiece in front of them. Bending fundamentals don’t go away, and nothing stops operators from learning about them. Also, how does the work fit within other pieces in the job? How is this job sequenced with other jobs? How’s the work presented from upstream, and what’s the best way to send this job downstream? Asking all these questions requires engagement, which in turn requires character.

The Storys’ message of character and competency ventures far into the “soft side” of company leadership, but considering the state of the labor shortage, it might be a side worth exploring. Managing things and processes is relatively easy; leading people is hard.

At industry conferences, talk of skilled labor often devolves into a series of complaints about societal problems. Kids today don’t want to work. This is what happens when everyone gets a participation trophy. I’m just happy if people pass a drug test and show up. They can’t even read a tape measure.

The Storys’ message: Judging and blaming gets you nowhere. Your people are your culture. Connect by being authentic, exhibiting humility, asking what they need, sharing knowledge, and showing how you and others can help.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI