Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How gainsharing differs from profit sharing and drives improvement

Sharing the gains helps align incentives across manufacturing and metal fabrication efforts

- By Tim Heston

- August 29, 2023

- Article

- Shop Management

The concept of being paid by the hour has a great disconnect that few give a second thought to, and it comes to light when anyone launches a business: Customers pay for results, yet companies pay workers for their time.

New entrepreneurs might think back to their days “on the clock,” remembering the time when Friday meant payday. Now, as a sole proprietor, the customer pays them for the results; in metal fabrication, that’s the fabricated product. When the business grows, though, a paradox emerges. The founders retain that entrepreneurial mindset, so they measure manager performance based on profits, sales growth, on-time delivery, and cost reduction. That sounds great. Thing is, people on the front lines—those hourly employees who actually do the work—are still paid for their time. The longer they work, the more they get paid, regardless of how much or how little they produce.

Carried to its logical extreme, workers are (at least in the short term) financially incentivized to produce as little as they can in as many hours as possible. And if productivity problems persist, they effectively get a 50% bonus (time and a half) to work overtime and fix problems that probably never should have happened in the first place.

“Gainsharing addresses that disconnect.” That’s Chuck DeBettignies, PhD, owner of the Indianapolis-based consultancy Gainsharing Inc. and frequent speaker at FABTECH.

DeBettignies aims to spread the gainsharing gospel. People are still paid for their time, of course, but under a gainsharing plan, their incentives align with what customers want and what the company needs to become more competitive.

An IndyCar Perspective

DeBettignies attended school just a block away from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, a place that in his mind stood apart for more reasons than the noise, smell of gasoline, and largest annual nonreligious gathering of human souls on the planet. The cars impressed him, but the people who drove and worked on them impressed him even more (see Figure 1).

“The people in these cars and on these teams, they just seemed alive. They were there to be the best, and it didn’t matter what it took. Every night, they’d take the car apart and inspect every piece. There was none of this, ‘Well, it should be good enough.’”

It was then that DeBettignies had a realization. “I saw that some people were having fun every day. They couldn’t wait to get up in the morning and tear into today’s excitement. Others went on about TGIF. So, through college, I kept asking, ‘How do we make companies like these IndyCar teams? It happens. We know it happens. But how does it happen, and how can we make it happen?”

Gainsharing vs. Profit Sharing

He went on to graduate school for work psychology and ended up working with a professor that focused on gainsharing, an incentive system that links employee bonuses to actual tasks they can control.

“Profit sharing pays out if the company beats goals set to trigger a payout,” DeBettignies said, “but it doesn’t tell people what they need to do to make profits happen.”

FIGURE 1. Chuck DeBettignies went to school just blocks away from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The cars impressed him, but the people impressed him even more. Tom Merton/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Sure, a company might set certain conditions; people might need to meet certain goals, for instance, either individually or collectively, but meeting those goals doesn’t guarantee a payout. Profit-sharing bonuses seem to “just happen,” DeBettignies said, “and people don’t know exactly what they did to make it happen.”

Put another way, the company might share the profits, but the drivers behind those profits remain shrouded in mystery. No wonder some thank a higher power that it’s Friday.

What is Gainsharing?

DeBettignies, who has a number of sheet metal fabrication clients, has visited plenty of shops and talked with many owners, managers, and shop personnel. After years of tours and in-the-shop conversations, he’s developed six foundational elements necessary to support a gainsharing program. Three deal directly with people while another three deal with the numbers and formulas needed to establish and pay out bonuses.

DeBettignies emphasized that the following shouldn’t be looked at as a step-by-step, sequential guide but instead as a tightly connected puzzle. For gainsharing to work, every piece really needs to be in place:

- Know your profit drivers (numbers) - Most custom metal fabricators operate businesses that might look simple on paper—the balance sheets and P&Ls don’t look that intimidating—but the nuts and bolts of job scheduling, routings, and resource management can be extraordinarily complex. Because of this, DeBettignies relies a lot on the 80-20 rule.

“Every company has three or four things that each drive 15 to 20 other things,” he said. “If you discover this short list, these primary factors, you’re driving the bottom line.”

Companies start by looking at the numbers during a particularly good week or month. What happened during those months that made them good? How much production did the shop have? What were the material costs? As DeBettignies put it, “This answers the question, ‘What does good look like?’”

Give feedback (people) - Once an operation knows what “good” looks like, managers give feedback, commending people for performance that meets or exceeds that good month, noting and (ideally) offering help for when performance falls short. Someone might not show up for work. A machine might break because a maintenance schedule wasn’t followed.

Develop that boots-on-the-ground connection (people) - This, at its essence, creates a to-do list—tasks that a front-line worker can act on immediately. “Here, the individual worker can see what they need to do today to do their part to drive performance,” DeBettignies said.

He added that this should go beyond a pieces-per-hour metric. Quality matters, as does the resources consumed and the consistency of throughput. Someone might overweld a joint, which wastes welding wire, not to mention time at the grinding station, and perhaps causes excess distortion. Someone might push a laser cutting machine hard, yet skip scheduled maintenance (cleaning the head, bellows, scraping the slats) and, in turn, cause unexpected downtime the next shift as problems arise.

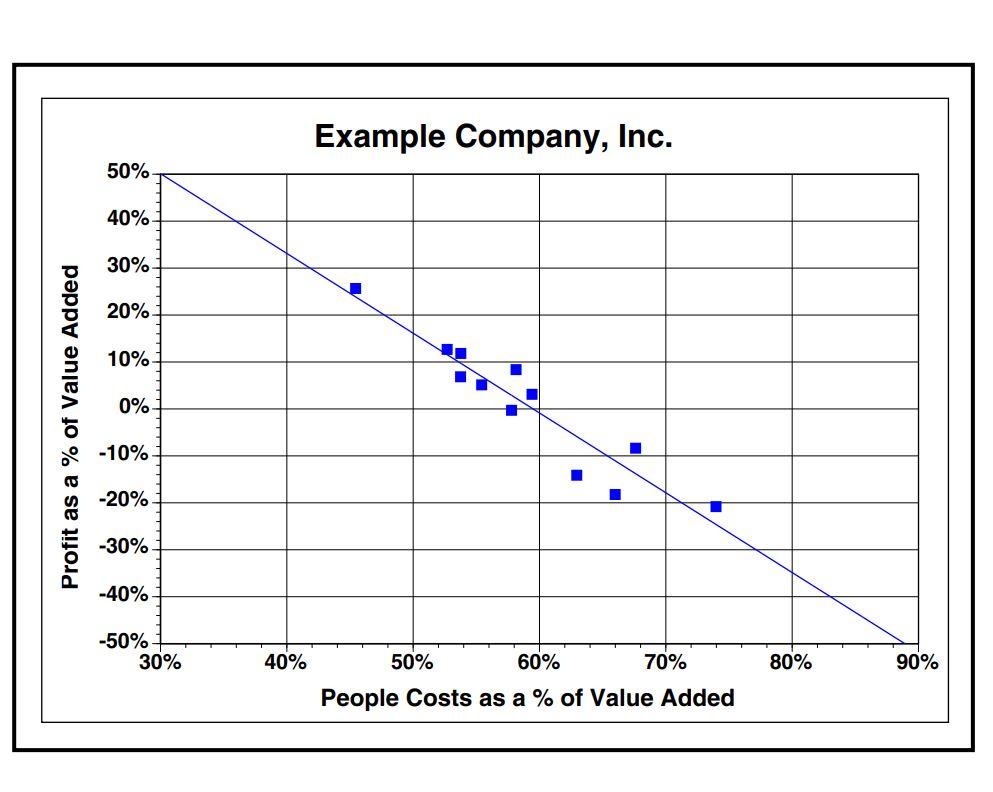

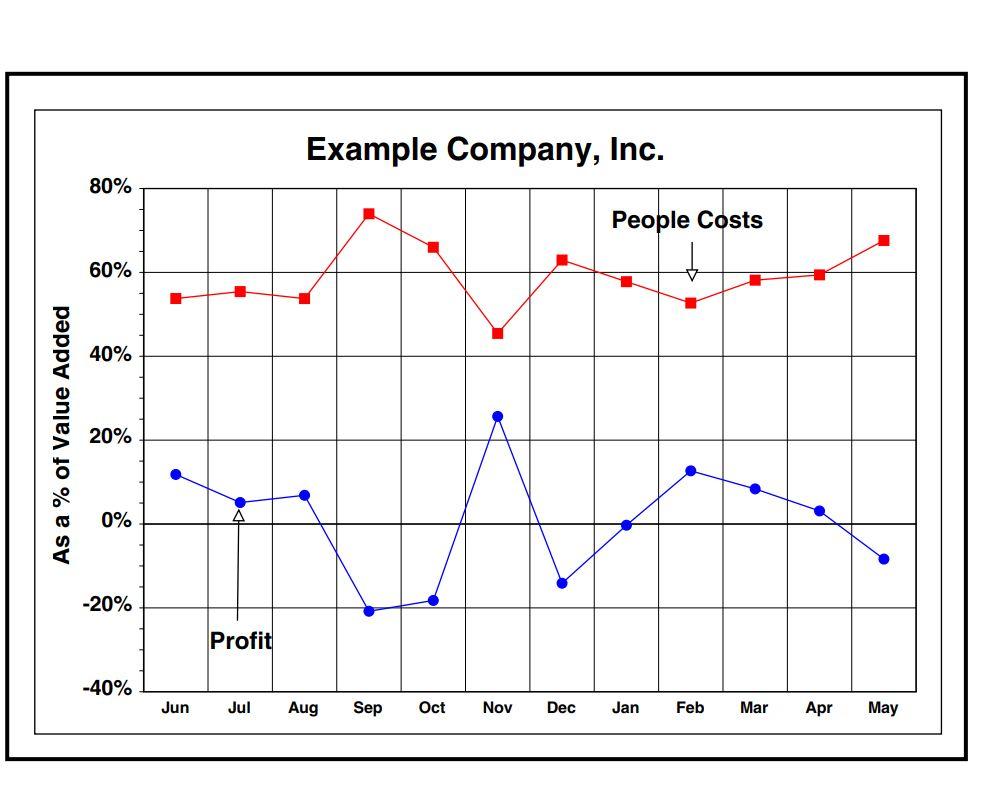

FIGURE 2. This measures payroll costs against value-added work—that is, revenue minus costs for material, purchased components, and outside services. For many operations, the relationship is clear: As payroll costs rise, profits fall. The idea is to increase the value each employee produces. Gainsharing Inc.

Similarly, someone in purchasing might be measured on the amount they save from vendors, but poor vendor performance can cost more than money saved. The same goes for not-so-level raw material that cuts, bends, and welds unpredictably (unexpected amounts of released residual stress in sheet metal can be a costly thing).

Develop fixes (people) - Talking with the boots on the ground, you next can start developing fixes to problems. For overwelding, this might include better training and incentivizing overall throughput in the joining department, from tacking and fixturing through welding and grinding. For purchasing, this might involve weighing raw material prices with certain quality and consistency requirements, along with a well-documented, rigorous vendor score card for all purchased components and services.

Develop a production plan (numbers) - This plan ties everything together, leveraging the incentive of gainsharing for continuous improvement. DeBettignies described setting the system to make it work like a game: The game prompts people to take action; they receive immediate feedback; and they get something they want.

Develop an incentive strategy (numbers) - Like any good game, a gainsharing program should give people something they want—in this case, a bonus that’s a percentage of the profits, distributed as a percentage of base earnings (to stay compliant with federal law) to everyone who’s eligible. (Some might institute some eligibility requirements; for instance, those under review for performance, attendance, or behavioral issues might not qualify.)

Profit percentages sometimes range between 3% and 5% and climb from there. The greater the gains, the more profit a company can afford to contribute. DeBettignies said he’s worked with companies that today distribute 10% of their profits or even more. It all depends on what makes financial sense, weighing the costs—paying close attention to the inverse relationship between total labor costs and profitability (more on this soon)—with the benefits of retaining and attracting better employees.

“It shouldn’t be just about the money, though,” DeBettignies said. “The results should show that you’re doing better than you did before, and that you’re doing your part. And by the way, we’re all making more money.”

“So, you put together a plan to keep everyone on track to get a specific bonus at the end of the month,” DeBettignies explained. “Then, we need to break down what we need to do, a to-do list, so every person can see their department and what their part of the total is. And you can tell immediately whether you’re on track.” DeBettignies emphasized that “gamifying” the plan doesn’t diminish its importance. On the contrary, it helps “pull people in.”

He added that the to-do list shouldn’t demand the impossible. It should be realistic, though still represent a gain (efficiency) that reduces cost and increases profit. The best lists have a mix of easily achievable items alongside goals that push people farther down the improvement path. “It’s like any to-do list. Do you ever place easy items on your list just so you have the satisfaction of crossing them off quickly? The same applies here.”

DeBettignies suggested that managers have a weekly plan. “It’s a cause-and-effect world. If you have a plan and you didn’t achieve it, there’s a reason why. If you don’t change the cause and effect, you’re going to have that problem again. The plan forces the discussion and forces the fixes to be put in place. And all this gets discussed with employees.”

Of course, metal fab can be a chaotic business. The best plans get thrown out the window by noon on Monday—so why write one? “Because if you don’t have a plan, there’s no reference point. Yes, the plan will change, but how much will change? If 20% will change, then get squared away with the 80% that’s locked in. Now we have to just worry about that 20%. This simplifies everything.”

The gainsharing bonus contrasts starkly with the profit-sharing bonus. Gainsharing is tied to actual work people do to drive profits. Profit sharing comes from just having a good month, quarter, or year. Purchasers might have gotten a good deal on material while sales might have landed a few good orders in highly profitable sectors. To someone operating a laser or wielding a welding gun, nothing much has changed, except perhaps for increased overtime to meet demand. And again, because their pay is largely tied to how many hours they work, they’re incentivized to work all the overtime they can get. Gainsharing helps realign incentives. The smarter (not longer) people work, and the more often they meet their goals, the more they’re paid.

DeBettignies emphasized that the first four elements, from establishing the profit drivers to developing those fixes (improvements), build a foundation for everything else. A gainsharing program can have the most generous financial incentives on the planet, yet if the true profit drivers remain a mystery, everything else falls apart, and people stay as disengaged as they always were.

The Weekly Production Plan

All this sounds great in theory: As profits go up, so does worker pay. But wait—wouldn’t those pay increases eat into profits? Fabricators need to reinvest to stay competitive. New manufacturing technology isn’t free. Is there a way for worker pay (bonuses) and profits to rise at the same time?

“This is where I take a company’s P&L, and I look for the elements that have an inverse relationship to the bottom line,” DeBettignies said, “and I sift away everything else. This way, the numbers reveal the 80-20 factors,” those with an outsized impact on everything else.

This can vary, but among many companies, including many custom fabricators, one relationship stands out: As total payroll costs rise, profits fall—specifically measured as a percentage of value-added work; that is, revenue less material, purchased components, and outside services (see Figures 2 and 3). The exact percentages depend on the operation, but in study after study, no matter how variable and complex a shop’s operation is, the relationship is pretty clear. “The value-added metrics cut through all this smoke,” DeBettignies said.

The clear relationship could promote some slash-and-burn management tactics. Want profits to rise? Cut the headcount! That isn’t sustainable, of course, especially these days. The last thing a fabricator wants to do is let go of highly trained, skilled personnel. So instead, the idea is to increase the value or return of every payroll dollar spent. This means shipping more (high-quality) work in fewer labor hours.

Here, the weekly production plan acts as a litmus test. When people regularly achieve their goals and receive bonuses, everything is on track. When people miss their bonuses regularly, something’s awry. Sure, it could be caused by broader business conditions, but it could also be caused by internal factors, like money-losing work that was underbid years ago and never adjusted to account for labor and material inflation.

The weekly litmus doesn’t prevent these problems, but it does bring them out into the open so that people can do something about them. It’s a virtuous cycle that might go as follows:

Step 1: Are we busy enough? The shop needs to have a certain amount of work on tap to give people a shot at achieving a bonus. People need to achieve a certain amount of throughput so that the company can pay its people. If the shop simply doesn’t have enough work, it has no gains to share.

Say that the shop needs to be able to ship $600,000 worth of work to achieve the necessary sales for a gainsharing bonus, working with direct and indirect labor costs of $70,000. “Going back to those profit drivers, this is what ‘good’ looks like,” DeBettignies said.That’s the general goal, but it doesn’t mean much to someone operating a machine. The weekly production plan in gainsharing aims to translate the broad goal into a detailed to-do list that workers can tackle.

Step 2: What does my group need to so to achieve a bonus? Here, the specifics come into play. The shop might have a new customer, and to achieve the weekly bonus, the production team needs to ensure the job flows through the routing at a certain pace. This translates into further specifics, like tool changeover and inspection requirements, ensuring smooth flow of this new job alongside existing work.

“Speaking broadly, like ‘We need to ship $600,000 this week,’ is a little like the teacher in Charlie Brown. Workers really don’t hear what you’re saying, because they don’t have specifics. They can’t act on it. Once you delve into specifics, like the new job requirements, new tooling, and specific processing challenges, their eyes will light up. And they’ll likely want you to stop talking so they can get started.”

Step 3: What do I need to do to earn a bonus? Front-line workers are asking this question, and for gainsharing to really work, they need to know the answer. This can involve specific tasks or goals to achieve every day to keep a job on track. From a practical standpoint, this resembles a production schedule—the difference being is that workers now have skin in the game: If they achieve these tasks today, they have a better chance of receiving that bonus at the end of the week. DeBettignies reiterated that, yes, things happen and the plan changes—usually by noon Monday, if not sooner—but tracking progress day to day at least gives people the opportunity to adjust as needed.

Step 4: If we didn’t achieve the plan, why not? Again, gainsharing doesn’t magically eliminate all problems metal fabricators face, but it does shine the spotlight on them so people can identify and work to solve them.

DeBettignies described several fab shop clients that faced a challenge that many likely know all too well: A job was stuck in the quality department (or other stage of production) and sat waiting for customer approval. Why? Perhaps some paperwork wasn’t updated to match some design-for-manufacturability changes. Perhaps the customer just missed an email or voicemail. Whatever the reason, it caused the shop to miss its gainsharing bonus target.

Before gainsharing, everyone might have just thrown up their hands and blamed the problem on a difficult customer. With gainsharing front and center, though, everyone turns their focus toward solutions. The next week (or the next time this or a similar job comes up), sales or customer service personnel have some fleshed-out tasks on their to-do lists. As DeBettignies described, “On Monday or Tuesday, you need to be actively contacting this customer, or I can’t ship this on Thursday. Everyone gets down to details, and gainsharing gets them there.”

Counterintuitively, such details help people broaden their view and pay attention to other details up and down the value chain. People in assembly know they need to finish a certain job on Thursday to achieve their bonus, but to do it, they need parts from cutting, bending, and welding. So, they pay attention, see when troubles arise, and actively work to overcome them before it’s too late.

With those details addressed, everyone starts hitting their numbers—that is, achieving the tasks they need to ship—and those gainsharing goals start to be achieved. As the virtuous improvement cycle continues, the shop becomes more competitive, the top line grows, and everyone shares in the gains.

Also, it’s not about working harder. As DeBettignies said, the greatest gains usually don’t come from working faster or trying to shave seconds off this cycle time or that job changeover—though, for sure, they’re important contributors. The greatest gains come from a shift toward a systems mindset. The person who emails and calls customers is just as important as the bending guru working through a challenging job at the press brake. If neither do their part, a job still doesn’t ship on time.

And when employees receive a bonus (or any other reward, for that matter), they know exactly what they did to achieve it. That satisfaction, DeBettignies said, is where employee engagement comes from.

Improvements Over Time

DeBettignies reiterated that the benefits of gainsharing happen over time. It won’t immediately eliminate money-losing jobs, but it does shine a spotlight on them. Do they lose money because of internal efficiencies? Or do we need to reach out to the customer for a price increase?

With gainsharing, everyone has a financial incentive to see change happen. Without gainsharing, the status quo’s just fine. In fact, front-line workers can actually benefit from operational chaos. After all, if everything goes awry, then they have a better chance of working overtime and getting the “bonus” of time and a half.

Gainsharing doesn’t eliminate overtime, of course, but it doesn’t incentivize it either. It also doesn’t hide the reality of a job shop. If anything, it highlights the problems and true complexities of the operation. Some jobs are challenging and have razor-thin margins; others are easy and produce sky-high profits. It depends on a shop’s core competency and prices a specific market sector will bear.

“A lot of times, working in a shop can be like driving in the fog,” DeBettignies said. Employees see what’s in front of them (the next job on the docket), but everything else is a blur. That, he said, is what keeps people focused on working more hours and coveting that overtime when, again, employees effectively get a 50% bonus (time and a half) to straighten out problems. In the short term, at least, the more problems there are, the more money they make.

“Gainsharing lifts the fog,” DeBettignies said. With weekly goals, everyone at least is aware of the challenges, and they’re incentivized to find ways to overcome them. Now, when severe problems persist, they still might need to work overtime, but the bonuses stop. The more problems there are, the less money they make.

Alignment accomplished.

During a presentation at last year’s FABTECH in Atlanta, DeBettignies quoted longtime UCLA basketball coach John Wooden. He was no gainsharing expert, of course, but he did understand its essence:

“When you improve a little each day, eventually big things occur. When you improve conditioning a little each day, eventually you have a big improvement in conditioning. Not tomorrow, not the next day, but eventually, a big gain is made. Don’t look for the big, quick improvement. Seek the small improvement one day at a time. That’s the only way it happens—and when it happens, it lasts.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI