Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Streamlining diverse part flow in metal fabrication

Georgia fabricator improves flow for 400 different jobs a week

- By Tim Heston

- October 7, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

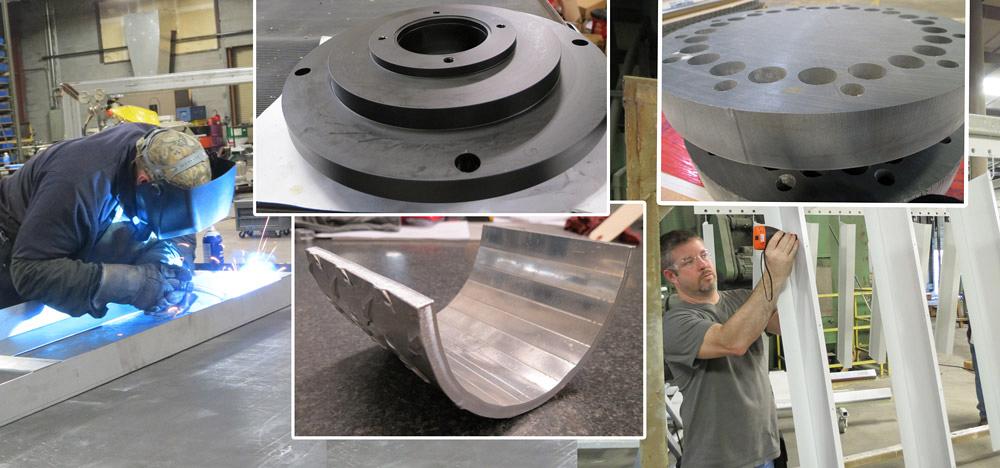

Figure 1

Prince Precision Products describes itself as a hybrid shop, able to cut, mill, turn, and form various workpieces

from gauge material to heavy plate.

Prince Precision Products (PPP) opened its doors in 2008 with a one-hit wonder, a military contract that brought in $8 million annually. The Macon, Ga., fabricator could have ended with that one-hit wonder too. But when that huge contract for armored parts ended, the shop didn’t shut its doors. It stuck around and grew its customer list. Today the shop’s 65 employees handle more than 600 active customers and, on average, more than 400 different jobs every week.

The company launched as a spinoff of Prince Service and Manufacturing (PSM), an industrial fabricator established in 1965 by Joe Prince. PSM specializes in large, heavy work like tanks, mezzanines, and other industrial fabrications, much of it produced quickly, delivered, and installed when customer plants are shut down for planned (or unplanned) maintenance.

PSM focuses primarily on heavy fabrication service and installation. But when the lucrative military contract came along, the founder’s grandson, Art Prince, saw an opportunity in piece-part and assembly manufacturing and so launched PPP.

For the past six years the company has grown off the small job. About a year ago, though, the company began expanding into more production work (a few thousand pieces versus a handful or a few hundred) as well as into more welding and assembly. The fabricator has evolved into a hybrid of sorts, processing numerous small orders, as well as some industrial and heavy fabrication work, and adding repeat production work into the mix.

PPP can cut, form, mill, turn, powder-coat, assemble, and ship (see Figure 1). It’s a metal manufacturing gumbo, and the taste comes from the right balance of ingredients. For the past year the people at PPP have been perfecting the balance and giving that gumbo some kick.

Managers Who Strike an Arc

PPP and PSM often work hand in hand. A machine at a local paper plant may need a precision gear cut out of 1.5-in.-thick plate, and PPP has the waterjets to cut the job before it’s sent to PSM for final fabrication and on-site installation. PPP and PSM also share personnel as needed. If PPP has a hectic week that will require a lot of welding, it may be able to pull a few welders from PSM. One welder, in fact, started working for PSM about 11 years ago, then came over to PPP shortly after it launched—but he didn’t come to weld.

Michael McNeal calls himself a bush beater, a salesperson who never hesitates to make that cold call. That’s an unusual attribute for someone who began working as a fitter and welder in his early 20s. After several years of striking arcs, he felt the entrepreneurial itch and left for retail. From his mid-20s until his early 40s he ran several TV, appliance, and furniture rent-to-own stores. “And I did all of my own advertising,” he said.

After two decades of dealing with the ups and downs of managing a retail store, he was ready for a change. So 11 years ago he left and went back to his welding roots at PSM. He enjoyed the hands-on work, but after several years he began to feel the sales itch once again. He also knew sales would be needed. The newly launched PPP had its military contract, but he knew that wouldn’t last forever. It needed more customers. It needed to diversify.

“I told the boss [at PSM], I know how to beat the bushes. I will find you new customers. And he gave me the opportunity, moved me from Prince Service and Manufacturing to PPP, and I’ve been doing it ever since,” said McNeal, now PPP’s director of business development. “We no longer have all of our eggs in one basket.”

A little more than two years ago, Jimmy Hittle also was looking for a change. He had spent years running a small manufacturing start-up, an operation focused on a family of products. Out of necessity, he learned to weld on the job so he could fill in on the line when needed. But he spent most of his days managing operations, sales, customer service, and all the other hats a small-business manager wears.

Figure 2

Jimmy Hittle (left) and Michael McNeal both started at the organization as welders. Today they’re helping company

leaders with several improvement initiatives to minimize rework, improve flow, and bring on new types of jobs, including

production work.

For a change of pace, he left that organization in New Mexico and came to Macon, where he got a job at PPP as a welder. Like McNeal, he wanted the predictability of clocking in, focusing on the welding in front of him, and clocking out. Still, his background was in operations, and he couldn’t help but observe and share his ideas. Managers at PPP saw potential, knew his background, and by fall 2014 promoted the welder from New Mexico to plant manager (see Figure 2).

Improving Flow

When it came to part flow, Hittle knew that PPP was utterly unlike the product-line manufacturer he left. The part and process mix in the cutting area alone shows just how high-mix the operation really is. PPP has lasers, of course, but it also has an abrasive waterjet system as well as a table with both plasma and oxyfuel torches. A few times during the past year the shop fired up the flames to burn through 12-in.-thick plate. About 60 percent of its work is carbon steel, while 40 percent is aluminum and stainless.

With all this variety, managers knew that balancing the load at work centers just wasn’t practical, but they also knew they could borrow some concepts from the product-line world. PPP operates out of 110,000 square feet, a portion of the building owned by the Prince family, renting other portions to tenants. (If PPP should need to, it could expand one day into previously rented space.)

Still, one drawback to the building is that it has a single shipping and receiving dock adjacent to powder coating and final assembly. Until recently the company stored all of its raw material at that end of the building, and managers realized how inefficient that really was.

The company has one 4-kW and one 6-kW CO2 laser, both with automated loading/unloading. This was all extremely efficient, except for delivering material from the loading dock all the way to the loading table at the laser.

At this writing, the company is fabricating a series of eight racks designed to handle 4- by 10- and 5- by 10-ft. material, as well as several more racks for 12-ft. material. In the future, sheet stock will be dropped off at a staging area at the receiving dock and then transported to the racks adjacent to the laser (see Figure 3).

PPP has also moved its wet flat-part deburring machine near the shake-out station for laser-cut parts, both of which now are directly adjacent to the press brakes. Near the forming area is what PPP calls the “special operations” department, which includes portable tapping arms, drill presses, and hardware insertion. If, say, a formed part requires hardware to be inserted in the middle of a bend sequence, the brake operator has access to the hardware presses nearby (see Figure 4).

Accounting for the Hot Job

It’s rarely planned for a work center to operate at more than 80 percent capacity, and additional buffers are built into the schedule. These buffers allow the company to bring in the hot jobs, which are common in most shops and especially prevalent at PPP, considering its customer mix.

The company’s top customers are in oil and gas, power generation, and food processing (hence the fair amount of stainless on the floor). Besides this higher-volume work, which PPP defines as several thousand pieces, the shop fabricates numerous small jobs that require extremely quick turnaround. A lot of this relates to plant shutdown work in which every extra hour can cost a customer millions.

As McNeal put it, “If a plant has idle machines that need a new part fabricated, every minute that ticks by is worth thousands of dollars. That’s when they call us.”

Figure 3

With these new racks, built near the laser cutting machines, PPP hopes to improve material flow between the raw stock area and loading tables at the lasers.

In an attempt to balance the work center load as best they can, the shop schedules certain jobs far ahead of the due date if time permits. Cross training plays a role, too, so that technicians can fill in where needed, be it in cutting, bending, or hardware insertion and other special operations.

Such cross training isn’t unusual these days, but when President and General Manager Art Prince and others strategized earlier this year about where PPP was heading, they knew they needed more to remain competitive and maintain on-time delivery, especially considering the shop’s product mix.

Like any job shop, PPP has to deal with many elements out of its control. It can streamline customer communication about design considerations, but it can’t always prevent a design change from happening before the job hits the floor. And it can’t prevent hot jobs; they’re an integral part of PPP’s business.

But it can work to prevent other variabilities—specifically, unexpected machine breakdowns and job rework. As managers see it, preventing these mishaps is central to PPP’s long-term success as a hybrid fabricator that thrives both on short-run work as well as production contracts.

Communication and Quality

Last year PPP discovered that regular preventive maintenance just wasn’t enough to prevent unexpected downtime. Despite regular PM, one machine in the cutting department broke down last year for several weeks. For two of those weeks, PPP was able to maintain on-time deliveries for all of its customers, a testament to how well scheduling with buffers works for the fabricator.

Yet why did the machine fail in the first place? It didn’t just occur out of the blue. Instead, the operator noticed something go awry several weeks before the incident. He tweaked the cutting parameters to overcome the problem so he could continue to churn out good parts. In the machine operator’s mind, he wasn’t doing anything wrong, and understandably so. He simply was using his expertise to keep products flowing.

Today the company has instituted regular meetings for machine operators, supervisors, and managers to keep tabs on operations, including any changes in equipment behavior. The meetings have helped communication issues and, most important, altered the company culture. It’s not about keeping quiet and churning out parts. It’s about observation and communication of machine operation, part flow, and, most significant, part quality.

“Rarely do we schedule so tight that we don’t allow for rush jobs,” Hittle said, “but we need to produce quality parts the first time. Rework will dramatically decrease our ability to take on those hot jobs.”

This is why Hittle spent time measuring parts earlier this summer in the quality department. He read blueprints, measured certain parts to ensure they met spec per the prints, learned the basics about how the quality department operated, and passed a certification test to demonstrate his knowledge.

Admittedly, he knew a lot about QA already, but that didn’t matter. Starting this past summer, every employee at PPP began receiving training in the quality department. This included welders, laser operators, even people in the front office—in fact, especially people in the front office. Problems on the floor often can be traced to miscommunication or misunderstandings that occur on the front end, be it between an engineer and estimator or a salesperson and a customer.

Figure 4

The company’s press brake area is adjacent to the special operations department, which includes hardware insertion. If a formed part requires hardware to be inserted in the middle of a bend sequence, the brake operator has access to the hardware presses nearby.

As sources explained, if everybody in the company receives basic training in QA, they begin to understand some of the fundamental engineering challenges of metal fabrication.

“This makes sure that everyone understands why certain dimensions [of a part] will or will not work,” Hittle said. “We all need to be tradespeople. That skill is not dead, and you need it if you want to make a product right the first time.”

“It’s a mindset,” McNeal added. “We’re spending a lot of time training employees so that everyone is part of the quality control system.”

Hittle added that these QA certifications vary depending on the person’s job function, and the training is somewhat basic; it doesn’t make everyone at PPP quality engineers. But it does get everyone in the company thinking in terms of quality and preventing rework. Everybody on the floor inspects their own work and signs off on the traveler. If the job traveler reaches QA without the appropriate signoffs, the QA tech takes the job back to the operator.

Hittle conceded that this may seem a little inefficient and bureaucratic, but he added that the policy helps ingrain the fact that catching an error late in the process, like in QA, can be extremely expensive.

Ideally, any manufacturability problem should be caught at the source, and quite often that occurs in the front office. Purchasing may need to order material from a specific source to overcome a forming problem; engineers may need to know about specific tooling requirements. And if a customer does have a revision, that needs to be communicated immediately to everyone.

Sources added that all this is being added to written procedures being prepared for ISO certification, which the fabricator hopes to achieve by early next year.

“We don’t want to be ISO on paper,” Hittle said. “We want to be ISO by practice.”

This thinking was behind a recent investment in powder coating, at the end of the manufacturing process chain, where rework can be extremely expensive. A noncontact gauge from Elcometer measures the thickness of the coating before it’s baked on in the oven (see Figure 5). Another new tool allows workers to measure baking and cure time accurately.

According to sources, the shop’s rework rate is less than 3 percent and its on-time delivery is tracking at better than 97 percent, which is above the industry average of near 88 percent according to the “2015 Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey,” compiled by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International.

Figure 5

This noncontact thickness gauge measures the thickness of the powder coating before it is baked on in the oven.

True, for a high-volume, low-mix manufacturing plant, 3 percent rework might not seem like anything to write home about, Hittle said, but not in a world of low-volume, extremely high-mix manufacturing, where stainless can be followed by carbon steel, and gauge material can be followed by 1-in.-thick plate.

“Remember,” Hittle added, “we’re processing about 400 different jobs a week.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI