Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

What makes a good business leader in manufacturing?

It starts with supporting employees and shop culture, not with control and optimization

- By Tim Heston

- July 15, 2022

- Article

- Shop Management

Over the past couple of years, a movement toward optimizing labor has been gaining strength at a lot of large companies. The idea is to cut out employees from the decision-making process, to use automation and software to control how their jobs are done, and to use artificial intelligence to predict their performance. Although the idea is in vogue with some companies, the data doesn’t support it with improved results. If anything, it deteriorates results, and it does so by taking responsibility away from workers.”

So said Joe Mazzeo, owner of Clarkston, Mich.-based Integrated Lean and Quality Solutions, in a seminar on lean manufacturing leadership during FABTECH 2021, held in Chicago last September. Mazzeo addressed a dichotomy that those in modern metal fabrication have dealt with for years: Fabricators use automation and modern technology to compete, and new operators can start producing parts quicker than ever. Yet if they aren’t trained to do more, they can become mere button pushers, warm bodies hired to produce but not think. They are, as Mazzeo said, treated like machines. That opens the door to labor optimization and treating employees as an asset to exploit instead of, you know, people.

At industry conferences and meetings among executives, talk goes on and on about the importance of company culture and employee engagement. It’s said that good culture starts at the top with good leadership. That might be true, but how does this happen, really?

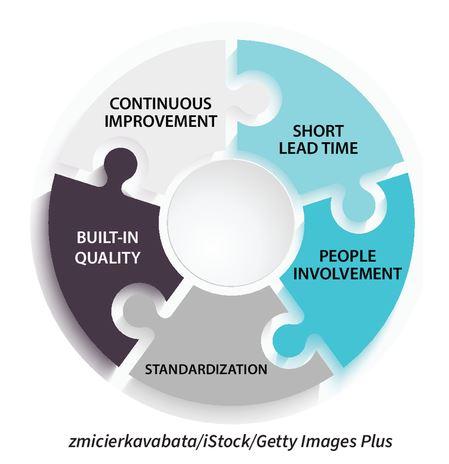

Mazzeo’s FABTECH presentation provided a roadmap. First, he explained that employee engagement is just one of five related pieces of a lean manufacturing system. The other four are standardization (standard work, documented processes), built-in quality (quality at the source), short lead time (for competitiveness and cash flow), and continuous improvement (idea generation). A leader really can’t engage employees and build culture in a chaotic shop with systemic problems.

Beyond this, Mazzeo described several building blocks of engagement, the first being the company vision and values, and the second being the company mission. “When you ask most people about their company’s vision and mission, most can’t recite it. The statements use flowery language, and most really don’t know what it means. The best ones are short and easily understood.”

For instance, instead of a mission “to be the No. 1 resource for metal fabricated products,” maybe try “to protect customer brands.” The market determines who’s No. 1, so “becoming the No. 1 resource” is partly out of employees’ control. But actions employees take directly—optimizing throughput, ensuring quality work, developing design-for-manufacturability ideas—aim to create a stable, reliable source of metal fabricated products delivered in the right quantity at the right time. In short, they’re protecting customer brands.

Health and safety form the foundation of another building block of engagement. Good leadership and culture can’t exist in an environment that doesn’t protect employees.

Having qualified people—or, more specifically, the right people in the right roles—is another building block. Most significant, leaders should ensure they or others can teach or coach people, enhance their skill, and measure their competencies. Nothing destroys company culture like ignorance and incompetence.

Another culture destroyer is that feeling of powerlessness, common when leaders micromanage among chaos (no standardization, 5S, or any kind of lean thinking whatsoever). Here, another building block of engagement—a team concept that empowers employees to function as owners over a particular work process—plays a role. Everyone on the team has documented roles and goals, so there’s no ambiguity.

Within this framework, employees participate in continuous improvement activities, see and gain pride in improvements made, which engages employees further—and the virtuous cycle continues. Such improvement happens in environments that foster a free flow of communication at all levels. And leaders at every level know the needs of the shop floor. They visit where the work is performed so they can understand and (most critically) support workers who operate machines and move and ship work. Without people on the front line, everything behind them falls apart.

Taking the labor optimization approach—where everything is carefully controlled from “central command”—companies might end up scraping the bottom of the talent barrel. They hire a warm body who can push a button and move material from A to B. They could have punch/laser combos with load/unload automation and automated panel benders and press brakes—all sorts of shiny toys that one would think could create a stimulating work environment. But alas, the culture isn’t right. Leaders purchase new equipment because, in truth, they’re just tired of dealing with unreliable, apathetic people. No matter what they do, it seems, employee turnover remains high. So, they take away responsibilities and design systems with machines and software to make employee turnover less disruptive.

As Mazzeo succinctly put it, “If people are treated like machines, they aren’t going to be willing to contribute. That’s dangerous.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI