Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Shop floor makes transition to paperless workflow

Specialty contractor Shapiro & Duncan embraces the digital frontier

- By Dan Davis

- January 5, 2018

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

Figure 1

In Shapiro & Duncan’s 50,000-square-foot fabrication shop in Landover, Md., large-screen monitors are placed near workcells so that personnel don’t have to walk far to access information, such as job instructions and prints. Photos courtesy of Shapiro & Duncan.

You might not associate a place where the floors need to be swept occasionally as being the environment where the digital future is alive and well. You also might not be familiar with modern manufacturing.

Specialty contractor Shapiro & Duncan Inc. has found its lane and is moving full-speed ahead down the information superhighway. The facility has gone paperless. Tablet computers and 40-in. monitors can be found all over the shop floor (see Figure 1). No one is manually inputting data or code into fabrication machinery. Production scheduling is based on what’s needed in the field, not when someone’s drawings are complete and sent to the shop floor first. It’s been a transformation that has helped Shapiro & Duncan maintain its place as one of the largest mechanical contractors on the East Coast, according to Engineering News-Record.

“If you don’t adapt to these technologies, you’ll be left behind,” said Chris Canter, Shapiro & Duncan’s director of virtual design, construction, and fabrication.

Taking Steps Toward Interconnectivity

Canter started working for the specialty contractor in 2001. At that time he was working on drawings, getting input from the contractors, taking information from blueprints, and preparing jobs for fabrication. The field crews who handled the installation of piping and plumbing fabrications, subcontractors, and the coordination department communicated occasionally, but that communication was not uniform. Consistently meeting delivery dates and scheduling production to avoid major lulls were always challenges.

In 2003 Shapiro & Duncan invested in its own fabrication shop. It was looking to take on most if not all of the fabrication of pipe and metal fittings used on the jobs awarded.

In the ensuing years, the company’s fabrication business expanded. The 10,000-sq.-ft. fab shop in Beltsville, Md., was no longer big enough to house all of the fabrication work needed for the company’s expanding business, so in 2007 Shapiro & Duncan moved into a 50,000-sq.-ft. shop in Landover, Md.

Not only was the fab shop moving to a new location, the construction industry was moving in a different direction as well. More general contractors and fabrication companies were embracing all that building information modeling (BIM) had to offer. With BIM—basically a 3-D model of a building project—job details could be accessed almost instantaneously, instead of searching huge drawings for specific details. Latest revisions could more easily be tracked. Architecture, engineering, and construction parties could more easily discuss job details because everyone was updated in real time with such modeling tools. BIM held great potential—and still does—for parties willing to embrace it.

“About that time we started seeing the advancements in technology, and we realized that we needed to get onboard,” Canter said. “We needed to utilize the 3-D drawing and what it could bring to the fabrication end of the business.”

Here are the steps that Shapiro & Duncan took to embrace that digital future in recent years.Software Closes the Communication Gap. Even in the mechanical construction business, where spool pieces, what the industry calls fabricated assemblies for the job site, can be quite large and awkward, the fab shop has the same goal as the typical sheet metal job shop: Get a high-quality part out the door as quickly as possible. That was not always the easiest task when digital connections didn’t exist among all of the stakeholders. For example, when changes occurred at the job site that might have affected spool design, that message wasn’t immediately delivered to the fabricating shop, where material may have already been purchased and fabrication plans made.

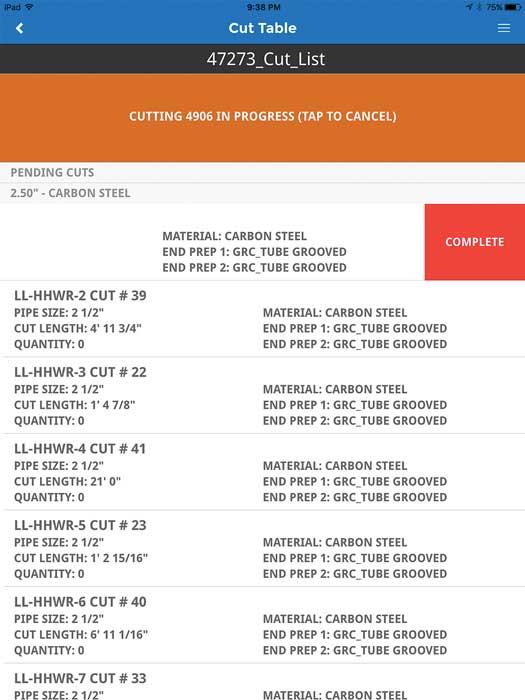

Figure 2

This phone view shows pending tube cutting jobs for one table. Theoretically, anyone with permission to access this information can see where a particular job is on the shop floor, eliminating the need for follow-up emails and phone calls from the job site or the front office.

In 2016 Shapiro & Duncan implemented FabPro1, web-based enterprise software that was developed by folks who had familiarity with the mechanical contracting business. The software has given the company the ability to connect all parties in the fabricating chain. Field management now has more say in terms of influencing priorities in the fab shop, and shop management has better visibility and control of project flow on the floor (see Figure 2). The field crew also has easy access to find out what’s happening in the fab shop and can share pertinent information, such as priority changes and even shutdowns (parts of a plant literally shut down for maintenance work), that can affect fab shop schedules. Screw-ups related to missed phone calls and deleted emails are eliminated.

“Anytime that you can break down those silos, that’s good,” Canter said. “You need to have that buy-in from the field on the product that is being pushed in the fab shop. If you don’t have that, you are going to fight it the whole way. Being able to show complete transparency brings the team together and opens up conversations. That’s what we were looking to do.”

Automated Equipment Makes It Easier. Advanced fabricating technology undoubtedly makes a large impact on any shop environment, yet if such machinery is not networked with the front office, a shop truly isn’t making the most of possible efficiencies. Shapiro & Duncan didn’t make that mistake.

Canter said the ability to network the equipment with the design department’s software tools allowed job instructions to be downloaded directly to the machines. Operators weren’t going to be required to input operational parameters anymore. That eliminated a redundant task and one more chance of human errors in programming.

Of course, such equipment also speeds up what was once tedious fabricating tasks. A beam line now cuts, marks, and moves the pipe downstream for further assembly per instructions pulled from the BIM file. Canter said such precision comes in handy when dealing with expensive materials such as copper. Software optimizes the cutting so that waste is minimized, and as each section is cut, it’s marked automatically with a tag that follows the pipe from the shop to the site for final installation.

Complete Visibility Is Introduced to the Shop Floor. If a fab shop wants to be responsive to change, it can’t rely on paper. That’s why Shapiro & Duncan invested in more than 25 monitors and even more tablet devices (see Figure 3) for the shop floor.

Now equipment operators actually keep track of cutting jobs, generated by the FabPro1 software, on the tablets. All drawings in assembly can be found on 42-in. monitors. Information is easily seen and simple to access. Everything also is updated in real time.

The Field and the Fab Shop Are Brought Closer Together. In 2015 Canter, who had been the manager of the company’s Virtual Design Coordination (VDC) department, where the spool design and fabrication job instructions were created, also assumed oversight of fabrication. It also was important because he had experience working with the fabricators and could easily understand their needs.

For example, he could see where some of the shop floor personnel might have issues reading the typeface on prints that were now being read on monitors. A few adjustments in terms of how the prints appear on the screen, and eye strain is averted.

“We can make those changes immediately and see the results on the fab shop floor,” he said. “Hopefully, it eased some of the pain as we made this transition.”

Figure 3

Tablets for accessing job details and production schedules are readily available for those who need them on the fabrication shop floor.

No Turning Back Now

Shapiro & Duncan’s fab floor has been paperless since June 2016. This transition has taken place during one of the busiest periods in company history. It’s been running two shifts now (about 40 employees on the day shift and 20 on the night shift) for more than five years.

“It’s taken some adjustment, but it is working,” Canter said.

To ease the transition, Canter paired more technology-savvy employees with others who weren’t as comfortable with the shift to the paperless environment. The buddy system proved beneficial in two ways: The technology neophytes got to see how to access files and documents and work with these new tools, something as simple as learning to pinch-zoom on a tablet, for instance, and the employees who had more computing experience than actual fabricating experience got to learn from veterans of the trade. Looking back, Canter said it took about eight months before everyone on the shop floor could interact with the software and display devices without encountering obstacles that required intervention.

The impact of the technology is evident in the way that Shapiro & Duncan is turning around jobs. Whereas jobs used to take weeks, from material delivery to shipment of the fabricated assembly to the job site, the fab shop is now targeting five-day work windows for most projects. Some stretch into the two-week range, but for the most part, most of the work is being turned around in a handful of days.

One of the biggest visual clues that this transition has occurred is the lack of material lying around the property. Canter said the company used to order as much material as possible and then it sat there until the job site called for it. That’s not exactly lean manufacturing, and the VDC team recognized it. Leaning on BIM and closer ties with general contractors and their schedules, the VDC has been able to bring in material as it’s needed, which helps to minimize raw material inventory.

How important is this digitization of fabricating information? Shapiro & Duncan now has 18 people in addition to subcontractors who help with the processing of 3-D models into work instructions and prints.

“In the early 2000s, I would never have imagined that we would get to the point where today we have an entire construction industry that relies on virtual design,” Canter said. “Without these guys in the VDC, we would be at a real loss.”Shapiro & Duncan, 301-315-6260, www.shapiroandduncan.com

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI